Arts

Sri Lanka: What is in store for us?

View(s):By Tissa Jayatilaka

To consider what the future holds for Sri Lanka, a glance at its past and present should prove useful as we could thereby contextualise and perhaps begin to understand what that likely future could be. Unless we look at our past mistakes dispassionately, attempt to learn from them and take meaningful steps to re-chart our national course, we are most likely to continue to allow history to repeat itself.

While it is doubtless true that Sri Lanka, like all other colonised countries, suffered immensely at the hands of those who colonised us, our track record of how our country (or constituent parts of it) has been ruled and governed by some of our own kings and nearly all of our politicians leaves much to be desired. Heaping all of the blame for our continuing miseries post- 1948, therefore, on our colonisers and colonial rulers who exploited and plundered us (sometimes with a little help from our ‘nobility’) from 1505-1948, as some tend to do, is to obscure the truth.

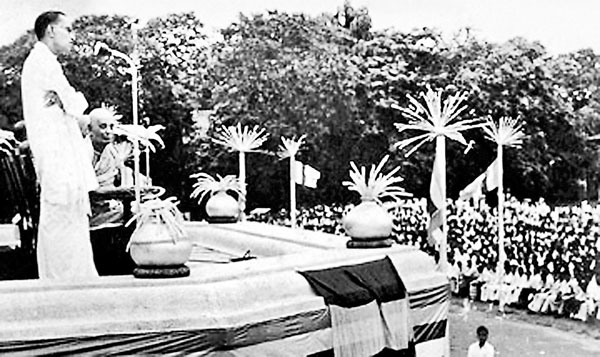

S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike established the Sinhala Maha Sabha in 1937

We ourselves have contributed lavishly to our own ruin as evidenced by our pre-colonial and post – independence history. That history tells us that, as in some other countries of the world, violence and intrigue have been very much a way of life in Sri Lanka both in centuries gone by and post-independence. Why we as a nation have not overcome these tendencies, is something we need to ponder on, if we are to move beyond such uncivilized conduct.

At the turn of the 20th century, Sri Lankans began to divide along ethnic lines.

From around the 1920s Sinhala – Tamil relations were on a slippery slope. The fact that politically shrewd and manipulative British Governors of Ceylon sought to divide and rule us is beside the point; for after all, Ceylon had a sufficient number of educated, experienced and sophisticated political leaders at the time who should have known better than to fall for that colonial bait. The notable Ponnambalam brothers who had hitherto spoken and acted in the best interests of the country in collaboration with their Sinhala colleagues, parted ways. They went back to Jaffna and together with a few of their Tamil contemporaries began to work for the betterment of their community.

A little more than a decade and a half later, S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike, who in 1926, upon his return from Oxford, had advocated a federal solution for the political ills arising from ethnic rivalry in the country, established the Sinhala Maha Sabha (1937) which was devoted to the promotion of Sinhala Buddhist interests. Bandaranaike had, like some other westernised Christian politicians, also become, what is referred to as, a Donoughmore Buddhist and donned the national dress. The above referred-to parting of the ways of the Sinhala and Tamil politicians, disturbed the harmony that had prevailed between them in the first two decades of the 20th century.

So we see, that the Sinhala and Tamil politicians were disunited even before we could secure independence from the British. What was infinitely worse was that the Sinhalese and Tamils were divided amongst themselves as well. The upper class and upper caste Sinhalese and their Tamil counterparts, believed that they, by birth and wealth, were superior to the rest of their country men and women.

Within three years after independence, the Sinhala and Tamil politicians split up. Certain members of the GG Ponnambalam-led Tamil Congress left in 1949 to form the Federal Party whilst S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike resigned from the United National Party -led government and formed the Sri Lanka Freedom Party.

Ponnambalam Ramanathan

Along with this ethnic division, was the social division based on class and caste. As Howard Wriggins (Wriggins:1960) has noted, Ceylon was made up of two nations, the Sinhala and the Tamil. There were also two other nations—those who spoke English and those who did not. The former was made up of both the public school elite and the western-educated elite. They held significant positions in the public service, the professions, business sector and politics. The government was carried on in a language the non -English speaking public did not understand. The social divide between the English-educated elite of the urban areas and the rest of the country, especially those in the rural areas, was evident to any sensible observer. At the same time, those Ceylonese who were educated in the English medium, regardless of ethnic differences, bonded together in a way the rest did not.

Despite the above-delineated ethnic and social divisions, post-1948 Ceylon could have emerged as a viable nation united in its diversity. For that to happen, a strong political will was necessary. After nearly four centuries and a half of colonial rule, in the aftermath of independence, there was a need for a revival of indigenous socio-cultural values. And this was admittedly a complex need. However, it was our misfortune, that a majority of the political leaders who guided the destiny of Ceylon at the time, with the possible exception of D.S. Senanayake, had neither the will nor the wisdom required to attempt to bring about an all-embracing national revival and hence succeeded in achieving only a Sinhala Buddhist revival.

Consequently, less than a decade after independence, “1956” came into being on the back of an extreme Sinhala Buddhist nationalism and Ceylon lost whatever was left of the opportunity to forge a pluralist society. We became a country of different ethnicities and religions instead of a robust nation held together by unity in diversity. As the years rolled by thereafter, Sri Lanka became, as the American academic Robert Kearney has put it, an unhappy reminder of the difficulty of maintaining an orderly and peaceful democratic process in a plural society when ethnic loyalties and symbols become central elements of political contention and outcomes are determined on a majoritarian rather than a consociational basis. (Kearney:1985).

Ponnambalam Arunachalam

The grim and dismal outcome of our missed opportunity to become a rainbow nation, is our painful present predicament. Today we have hit rock-bottom economically and politically. To say that the Sri Lanka of today is in chaos is to state the obvious. Even faced with dire challenges to our very existence as a country, we continue to remain divided as ever, with each of our political outfits clamouring to ride into political power at whatever cost. Each political party has miraculous solutions to our national woes which they “threaten” to implement, as the Rajapakse cabal did whenever elected to office. A need to have a dialogue with the electorate on key issues, prior to an election is, strangely, not deemed important.

In the latter political context, it is useful to recall the damning indictment of our political reality by U.B. Wijekoon, a former prominent politician. In a booklet titled The Curse of Party Politics (no date, probably 2008), Wijekoon tells us that politicians from all backgrounds tend to look at any national problem with the sole intent of seeking an advantage to win elections, disregarding principles and values. Furthermore, he observes that our political party system has wrought havoc by misguiding our society, denying the country of a coherent social fabric and economic equity, and in the process creating grave national instability. He notes that in Britain, whose political model we have chosen to follow, over a period of five centuries only three political parties came into being, ‘whereas in Sri Lanka, political parties exceeding fifty-nine (59) have been registered within a short span of 60 years’. Wijekoon goes onto say that our politicians are not accountable to the people who elect them, and that virtually all of them are guilty of bribery and corruption. With meagre incomes most politicians manage to send their children to international schools in the country and then to universities abroad. What Wijekoon told us in 2008 remains valid even today!

One of the most pressing needs of the day, if we are serious in our intent to resurrect Sri Lanka from the depths to which it has fallen, is to curb and minimize corruption. Corruption as defined by the Malaysian academic Syed Alatas, is the abuse of public trust for personal gain, and it is rife both among our politicians and, tragically, amongst members of our public service as well. Until we implement fully, sans political interference in the judicial process, the existing laws of the land and legislate necessary new laws to combat rampant corruption, it is unlikely that much will change in our country in the years ahead.

Another crucial need, however belatedly, is to make a genuine effort to forge national unity. So long as all of us are not treated as Sri Lankans, regardless of our ethnicity and religion, so long will we continue to flounder as a state nation instead of becoming a nation state. And until Sri Lanka stops discrimination of its citizens on the basis of language and religion, there will not be meaningful and consistent socio-economic development in our thrice-blessed land. Sri Lanka has to curb its militant Sinhala-Buddhist nationalism which, its politicians and a segment of its Buddhist clergy, (contrary to the teachings of the Buddha) are guilty of. Ever since the early 1950s, when the Eksath Bhikku Peramuna (EBP) came into being, Sri Lanka has been plagued by violence against the non-Sinhalese, orchestrated by unscrupulous politicians seeking to win elections by hook or by crook, with the aid of lesser mortals among the Buddhist clergy. This is unacceptable and totally contrary to the ethics and principles enshrined in the Buddha Dhamma.

None of the above can be achieved without a radical reform of our education system. The key element of such a reform should be the teaching of an inclusive History in our schools. The History we are presently taught, even before each of us can begin to distinguish right from wrong, tells us that our non-Sinhala fellow citizens are evil because the Tamil kings of old harmed the Sinhalese or because South Indian Tamils (the Pandyans and the Cholas) invaded us ages ago, between the 9th and 10th centuries; and that militant Islam poses a threat to Buddhism while Muslim traders and businessmen impoverish their Sinhala counterparts. Surely it is about time, we Sri Lankans shed our primordial prejudices, fears and complexes and learned to live in peace with one another.

In addition to the teaching of such an inclusive History, the future generations should be introduced to the tenets of all the major religions, taught the basics of ethical behaviour as a part of their school curriculum combined with the essence of literature and philosophy to create well-rounded future citizens. In this endeavour, early academic specialization should be discouraged, at least until after the GCE Ordinary Levels.

As Arjuna Hulugalle (The Island; 16 April, 2009) observed almost fifteen years ago, the introduction of tri-lingualism is a must. We have come a long way since Dr. Colvin R. de Silva said, One language two nations; two languages one nation. Important as the two languages Sinhala and Tamil are, they are insufficient today for our purposes. Hence, in addition to teaching both indigenous languages to all Sri Lankan students, they should be taught English because a knowledge-based society needs to have access to the world outside its shores.

Tri-lingualism for Sri Lanka is necessary also because language will play an important role in the process of reconciling and uniting all our citizens. Countries like Switzerland, Finland, Canada and Singapore to name but a few, give equal importance to all the languages spoken within their borders.

Our education system should be reformed as outlined above so that Sri Lanka could aspire to inter-ethnic, inter-religious and inter-cultural harmony without which, only further misery will be in store for us in the years to come. These changes to our educational system, though essential, can only produce results after many years. Among the short to medium term measures that could be adopted to address the anomalies in our system, the following measures could be considered essential and immediate:

- Merit-based selection for all public service appointments;

- The conferment of equal status to all national languages, religions and citizens;

- Gender equality; and,

- The strict adherence to equal application of the laws of the land to all citizens irrespective of their social and political status.

- (The writer is a former academic and an academic administrator)