Arts

When a disgruntled Kandyan kingdom rose up against the British

View(s):- Remembering Keppetipola Disawe, pioneering freedom fighter

By Udumbara Udugama

February 4, 2024 marks the 76th anniversary of Sri Lanka’s Independence from the British.

The island first came under foreign rule in 1505. The two European powers, the Portuguese and the Dutch, were able to establish themselves in the maritime provinces, the Portuguese wielding power from 1505 to 1658 and the Dutch from 1658-1796. Although both aimed to capture the Kanda-Udarata, the Kandyan Kingdom, they were unsuccessful. The last battle fought by the Portuguese was at Gannoruwa, close to Kandy in 1638, where they were badly defeated. In 1796, the British invaded Kandy after displacing the Dutch from the maritime provinces.

The Kandyan kingdom was ceded to the British on March 2, 1815, the document signed by the British Governor of Ceylon, Sir Robert Brownrigg and the Kandyan chieftains, thus ending the independence of the Kandyan kingdom. Even on that day, just before the agreement was signed, the resistance to British rule was displayed. As a soldier took down the Ceylon flag to hoist the Union Jack, Ven. Wariyapola Sri Sumangala Thera walked up and hoisted the Ceylon flag, pointing out that the country was not yet under the British rule.

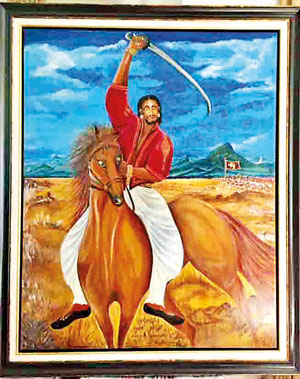

Painting of Keppetipola by Avanti Karunaratne at the Dalada Maligawa museum

Within a few months, the Sinhalese were dissatisfied with the British administration, as they did not keep to the clauses of the Convention which stated that the traditional laws, customs and powers of the chieftains would be maintained and Buddhism, the clergy and places of worship would be protected. The chieftains, Buddhist clergy and the people had discussions to overthrow the British but rivalry amongst certain chieftains led Ekneligoda Mohottala to reveal the plot to the authorities. The chief translator in Kandy, William Trolfey informed the Governor of this conspiracy in the Kandyan areas. Madugalle Nilame, a chieftain was arrested and imprisoned, but subsequently released under an amnesty by the Governor.

The 1817-1818 uprising in Uva-Wellassa was the first independence struggle by the people of Wellassa. The uprising began in October 1817 triggered mainly by the appointment of a Moor, Hajji as Muhandiram to Wellassa. During this time an imposter named Doraisamy who claimed to be the son of King Sri Wickrema Rajasingha’s brother was seen in Wellassa. He was a man named Wilbawe who had been earlier ordained as a monk. Assistant Government Agent Sylvester Wilson on October 12 had sent Hajji Muhandiram to apprehend him but on his way back, Hajji was murdered by a group of people. On receiving this news, Wilson went to meet the rebels in Wellassa but his discussions with them were futile and on his return to Badulla, he was killed.

The British Commissioner in Kandy, Marshall Sawers sent one of his high ranking officials Keppetipola Disawe to Uva to report on the situation. Without taking any soldiers, Keppetipola selected 12 of his faithful men and left for Uva. On arrival, he met Butawe Rate Rala, Maha Badulugama Rala and Kiule Gedara Mohottala. They convinced Keppetipola Disawe that he should join them and lead them in their struggle to send the British away and have a Sinhala king as ruler. Keppetipola decided to join them and sent the 12 men back with the government issued muskets and ammunition with a note to Sawers saying he had joined the rebels to save the country from British rule. Although he knew that Doraisamy was an imposter, he accepted him and named him King Weera Wickrema Keerthi. Maha Badulugama Rala, Butawe Rate Rala, and two others were appointed as his officers. Keppetipola was designated Adikaram.

The uprising gained strength with more peasants joining in, also helped by the Adhivasi (Veddah community). By January 1, 1818, the whole of the Kandyan kingdom was fighting to gain their lost independence. The Governor declared martial law in the Kandyan provinces.

Governor Brownrigg convened a meeting at the Magul Maduwa (Audience Hall) in Kandy and addressed the Chieftains. He read a proclamation declaring Keppetipola and 18 others to be rebels, outlaws and enemies of His Majesty’s Government. Their lives were accordingly forfeited and property confiscated. A reward of 1000 gold pagodas were offered for each of the heads of Keppetipola, Pilimatalawe and Madugalle. The Governor’s speech was translated to Sinhala by Abraham de Saram.

Intense fighting was going on and at one stage, the British Secretary had sent a letter requesting the Governor to withdraw. But the letter came too late, as by then extra forces were sent from India to strengthen the British Army. This was a big blow to Keppetipola.

The rebellion failed due to many reasons. The Sinhalese fighters were weak and many succumbed to various sicknesses. The British destroyed the paddy fields and vegetable plots by burning them. The people were starved and had no strength to continue fighting. By October 1818, they did not have sufficient weapons. Their will to fight waned with the leaders falling sick. Another advantage for the British was the support from certain chieftains in the area who permitted their troops to cross their territory and obtain supplies.

Lieutenant O’Neil captured Keppetipola and Pilamatalawe on October 28, 1818. Monaravila Keppetipola was tried by court martial on November 12.

Dr. Henry Marshall, Director General of the Army Hospital in his book ‘Ceylon, Description of the Island and its Inhabitants, writes that he found Keppetipola conducting himself in prison with much self-possession. Marshall also recorded the tragic final moments of Keppetipola Disave and Madugalle on November 26, 1818. At their request, they were taken to the Dalada Maligawa and met by Mr. Sawers. The monk on duty explained the meritorious acts done by Keppetipola, pronouncing his prarthana (last wish) that in his next birth he might be born in the Himalayas and finally attain Nirvana.

He requested Sawers to see him being executed but Sawers declined. The prisoners were then taken to Bogambara. Before his execution, Keppetipola took out a small book of Buddhist stanzas from his waist and gave it to a soldier to be given to Sawers as a memento, as he had worked with him in a cordial manner.

Keppetipola’s cranium which was of somewhat unusual size was later presented by Marshall to the Museum of the Phrenological Society of Edinburgh. It was returned to the country in 1954 after independence and is now enshrined at the Keppetipola Memorial at the Maha maluwa in front of the Dalada Maligawa, in Kandy.

“Had the insurrection been successful, Keppetipola would have been honoured and characterized as a patriot instead of being stigmatized as a rebel and punished as a traitor,” were Marshall’s words.

The peasantry underwent severe hardships under the Colonial Government. They were forced to work on roads and had to pay heavy taxes to be exempted. This led to another upheaval in 1848, the Matale rebellion, led by Gongalegoda Banda and Puran Appu, the latter who came to Matale from Moratuwa, a coastal town. But the powerful British Army was able to subjugate the rebels. Puran Appu was captured, tried and executed by firing squad in Matale on August 8, 1848. Gongalegoda who fled was subsequently captured from a cave in the Elkaduwa area. He was tried and condemned to be hanged. But later by a proclamation the death sentence was amended to flogging and deportation to Malacca (Malaysia).

However, the 20th century independence movement was more peaceful. Anagarika Dharmapala was inspired by Mahatma Gandhi’s “non-violent movement for independence and revival of nationalism.” The pioneers for self rule were mostly from the educated middle class. The leadership for the movement was given by D.S. Senanayake, D.B. Jayatillake, F.R. Senanayake, E.W. Perera, T.B. Jayah, Ponnambalam Ramanathan, C.W.W. Kannangara, Ponnambalam Arunachalam, Henry Pedris, N.M. Perera, Phillip Goonewardana and S.A. Wickremasinghe to name a few. Henry Pedris was executed by the British authorities falsely accused of inciting racial riots. His death, at a very young age was a strong reason that provoked the independence movement to hasten the independence of Ceylon.