A writer of history rather than a ‘historian’

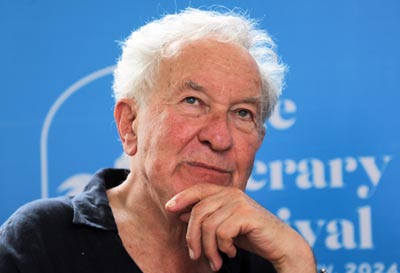

Simon Schama. Pic by M.A. Pushpa Kumara

Sir Simon Schama became the Face of Britain Past when, in the early 2000s, he hosted that haunting BBC TV series called A History of Britain, which took us from troglodytes in chalk-cliffed Cornwall to the British Empire that covered more than half the earth. Dramatic and moving, it was the boiled-down essence of much scholarly work.

Schama is much more than a TV historian though, having written books that have a popular appeal with firm erudite backing. While a few books like Patriots and Liberators, about the fate of the Dutch republic in the end of the 18th Century, were not meant for the general reader, most were the complete opposite of what he calls ‘boring fact after fact after fact’.

As we meet at last month’s Galle Literary Festival Schama still has that on-screen charisma, though 24 years have passed since he energetically pitched into the layers of chalk and peat.

“A historian at Cambridge once talked about the ‘secret poetics of history’- the romance of the past that spellbinds us as children and makes us historians”. Little Simon too was taken to the grim but fascinating Tower of London and ruined castles by his father. He also read Puck of Pook’s Hill, Kipling’s English idyll, and Robert Louis Stevenson.

Schama recalls being mesmerized by the Bible’s history of his own people, the Jews, even if it was ‘very inaccurate and unreliable’- and this sparked another fascination that was to finally flower in his three-volume The Story of the Jews (the third yet to come).

Schama shrugs off criticism at A History of Britain. He was accused by some lofty parties of ‘dumbing down’. But these are, as Schama points out, people who have never done TV shows. Once within ‘the box’, history should ‘not confuse people, must have a clear line through the plot’ and in fact has to be handled with ‘a set of skills not identical with academic skills’.

From classical times, historians have been storytellers as were Herodotus, Tacitus and Livy. What Schama calls ‘atmospherics’ is important to history as much as it is to a novel but in the former it must all rest on records and archives.

While writing his book on the French Revolution (still a go-to reference) he had to know what the weather in Paris was like on certain days in 1789, and miraculously he was to unearth the diaries of an aristocrat-turned-rebel who had an obsession for recording the day’s weather in detail for five years.

In a world of hedgehogs, he himself is a fox, states Schama with laughter. He is referring to a story related to him by mentor Isaiah Berlin, “who got it from Tolstoy and who in turn got it from the Greek”: “The world is divided into hedgehogs and foxes. The hedgehog is a small animal who knows one big thing; and foxes like to know many things.”

His catholicity of interests means he has no pigeonhole to cosily occupy. He is into art history and French, Dutch and Italian history, has championed Jewish history and explored Shakespeare in quite an avant-garde way with the BBC.

These interests are inter-woven. His love for the Netherlands is connected to a passion for Dutch art – paintings, engraved glassware, house signs – and his high regard for journalism as a ‘noble profession’ comes from the days when he moonlighted in the 1960s as an art critic for Timeout and the Times Literary Supplement and also the Sunday Times UK.

He had always deemed himself a writer of history rather than a ‘historian’. As he quotes E.M. Forster’s paraphrasing of Kipling, “what do they of history know, who only know other historians?”

“But (in order to be a good writer) I really (had to be) conscious about the rhythm of a chapter, of the tonal quality, the style of narration…”

“The way the words lie down on the page have been important to me.” He is an avid editor and loves it when, by ‘some mysterious alchemy’, ‘a fall of words seem just right’, while not being just description.

His book Foreign Bodies: Pandemics, Vaccines, and the Health of Nations, was a post-COVID offering that reminds us pandemics have the habit of popping up motif-like in human history.

Finally, there’s his work against anti-Semitism. While he had been a fierce critic of the Israeli policy, he believes it is his duty not to retreat to his ivory tower but to take to the streets against hatred of Jews. “You can’t just behave like a professor- hiding away.”

While evoking the French-Jewish historian Marc Bloch who was killed for his resistance to anti-Semitism, Schama laughs he is ‘not volunteering himself to be killed’ but he admires that public act and spirit not confined to the university walls.

Says Sir Schama: “I would like to carry on doing that now, when the world is in so much trouble in so many ways…”

Searching for an ideal partner? Find your soul mate on Hitad.lk, Sri Lanka's favourite marriage proposals page. With Hitad.lk matrimonial advertisements you have access to thousands of ads from potential suitors who are looking for someone just like you.