News

Halt mushrooming medical faculties

View(s):- Urgent look at SL’s need and also facilities & human resources to train students essential, say experts

By Kumudini Hettiarachchi

Mushrooming medical faculties sans a needs-analysis based on Sri Lanka’s requirement of doctors as well as the available facilities to train hundreds of students to ensure patient safety are causing serious concern among health experts and the public.

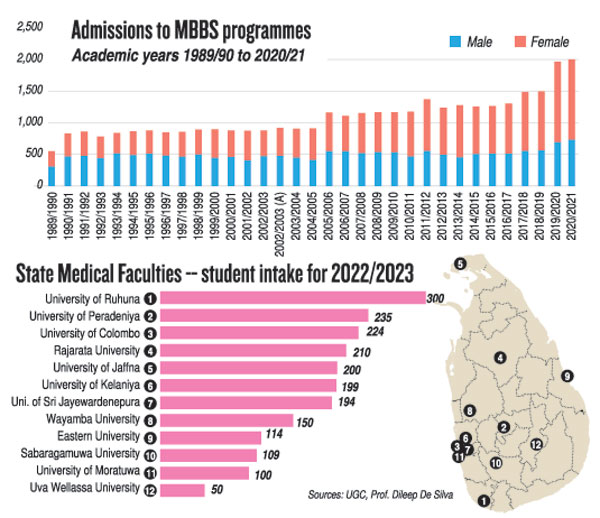

Currently, Sri Lanka has 12 state medical faculties; one military medical faculty at the Kotelawala Defence University (KDU) with a fee-paying civilian student intake included; and about three private medical faculties, including the National School of Business Management (NSBM) and Lyceum, in the pipeline.

The state medical faculties are at the University of Colombo; University of Peradeniya; University of Jaffna; University of Ruhuna; University of Kelaniya; University of Sri Jayewardenepura; Eastern University; University of Rajarata; University of Wayamba; University of Sabaragamuwa; University of Moratuwa; and University of Uva-Wellassa. (See graphic)

Trouble has been brewing within some state medical faculties with regard to a dearth of facilities and essential clinical training which would ensure that they do not spew out half-baked doctors who would be a danger to patients.

The Sunday Times understands that with lots of protests from various quarters and a professorial unit issue cropping up at the Sabaragamuwa Medical Faculty which is supposed to train its students at the Ratnapura Teaching Hospital, some sort of agreement has been reached for the hospital’s Consultants/clinicians to teach the students along with the university staff.

Over the years though there have been “territorial” concerns between medical faculty academics who are employed by the Higher Education Ministry and hospital Consultants/clinicians who are employed by the Health Ministry.

The Sunday Times also learns that brain drain has badly hit some of the medical faculties as well, with an example being cited of a pharmacology lecturer doubling up as a paediatrics lecturer at one medical faculty.

Sustainability of some of the 12 state medical faculties is also being questioned, with many raised eyebrows over retired academics and doctors taking up key positions at a few of these institutions.

Another major concern in the state health sector is that clinicians would be lured into taking up academic positions in comfortable towns, further crippling services to the poor of the country, already affected by the brain drain of specialists in search of greener pastures abroad.

This scenario would be exacerbated by the proposed private medical faculties which would offer more lucrative employment not only to academics in the state medical faculties but also to heavily-burdened clinicians, others were quick to point out.

Before looking at what ails medical education in Sri Lanka, Specialist in Health Finance and Health Management, Prof. Dileep De Silva glanced back at how it has evolved over the years.

The Colombo Medical Faculty was opened way back in 1870, followed about 90 years later by Peradeniya (in the 1960s); Jaffna about 15 years later (in 1978); Ruhuna soon after (in 1980); Kelaniya about 11 years later (in 1991); and Sri Jayewardenepura two years later (in 1993). After a lull of about 12 years, Batticaloa followed (in 2005); Rajarata coming hot on its heels the next year (in 2006); Wayamba being born 10 years later (in 2016); Sabaragamuwa three years after (in 2019); Moratuwa the next year itself (in 2020); and Uva Wellassa three years later (just last year in 2023).

“Poor planning has been the bane of the country including in medical education,” pointed out Prof. De Silva, reiterating that what should be taken into account before any more medical faculties are opened includes: what are the employment prospects of all these doctors being churned out; does the country need so many doctors or is our economy able to meet the demands of such a large number; and are there adequate facilities and human resources to train these large numbers of doctors.

These facilities and human resources would include hospitals for clinical training and experienced staff to undertake the training, he said, stressing that data collected from the Deans of all 12 state medical faculties revealed that the intake of medical students exceeded the manageable capacity in many of them.

Delving into technicalities, Prof. De Silva said: “The optimal number of doctors to be trained is contingent upon multiple determinants, including population size and distribution; economic dimensions such as the size of the economy and fiscal capacity; healthcare system structure and financing mechanisms; market characteristics; and geographical expanse of the nation.

“The phenomenon of oversupply of doctors observed in certain countries has led to adverse outcomes such as unemployment, under-employment and supplier-induced treatment, thereby diminishing living standards and professional recognition. These circumstances can exacerbate supplier-induced demand within the private sector. To mitigate these challenges, it is imperative for medical professional bodies and regulatory authorities to conduct thorough assessments of market dynamics.”

He urged that strategies should be devised to regulate the establishment of new medical colleges and implement policies aimed at aligning workforce supply with demand.

Such measures are essential to foster a sustainable and flourishing medical profession while upholding standards of quality patient care, he added.

“Let’s not produce substandard doctors – ‘many’ docs but ‘poor’ healthcare”

Underscoring that any country including Sri Lanka needs doctors, the President of the College of Medical Educationists, Prof. Gominda Ponnamperuma, pointed out that doctors, however, cannot work in a vacuum. “Doctors need other healthcare professionals and infrastructure facilities to engage in meaningful patient care. So, increasing the doctor population in the name of increasing patient care, without considering the rest of the healthcare landscape is a lopsided exercise,” he said. Explaining that unlike other commercial commodities, medical education should not be demand driven, he was quick to point out that it should be need/supply driven. Just because there is a demand for medical education, opening up medical schools without analysing the need to produce doctors, would give rise to a paradoxical situation where there are many doctors but poor healthcare. “If medical schools (private or public) are opened without paying due consideration to the resources (both human and physical) necessary to produce competent doctors, it would lead to substandard patient care. Human resources or teaching staff are the most hard to generate in the short term. This is while even though the country is cash-strapped, increasing physical resources is relatively easier than increasing human resources,” he said. Prof. Ponnamperuma stressed that producing substandard doctors due to lack of resources would have dire healthcare consequences. The calamity that we see and hear when a few drugs are substandard would get augmented several fold, if the prescribers of ‘all’ drugs become substandard. “The only way to prevent the deterioration of medical education and degradation of patient care is to lay down clear guidelines on minimum standards that every medical school should comply with and closely monitor the process of delivering medical education in these schools,” he said, urging the strict regulation of medical education from the very beginning to the end, as an ongoing process. He was categorical that the regulation should start at the conceptual stage of establishing a new medical school – many months/years before the admission of students to a new medical school. “For, if the country earns a bad reputation over substandard medical education, that will jeopardize the government’s efforts of making Sri Lanka an education hub, as no foreign student would come to a country that offers poor education,” added Prof. Ponnamperuma.

| |

| The country’s health force Here is a look at the health force as at December 2021 through Health Ministry data and a projection of what Sri Lanka would need in 2030 by Prof. Dileep De Silva Health force in December 2021:

Health force projection for 2030:

|

The best way to say that you found the home of your dreams is by finding it on Hitad.lk. We have listings for apartments for sale or rent in Sri Lanka, no matter what locale you're looking for! Whether you live in Colombo, Galle, Kandy, Matara, Jaffna and more - we've got them all!