Sunday Times 2

Easter attack on Ceylon: 82 years ago

View(s):During the height of World War II, on Easter Sunday, April 5, 1942, the Japanese bombed Colombo. A soon-to-be-published volume titled ‘Japanese Maritime Attack on Ceylon WW11’ by Henrick Melder provides an exhaustive account of those momentous times.

In these extracts – exclusive to the Sunday Times, the author traces the tense days immediately after April 5.

Dr Hiran W. Jayewardene and Capt. Gihan A. Fernando are the joint editors of the book.

Chapter 7- Anticipating the Next Attack

The Ceylon Daily News reported the raid on Monday, 6 April 1942: “Colombo and the suburbs were attacked yesterday at 8 o’clock in the morning by 75 enemy aircraft which came in waves from the sea. Twenty-five of the raiders were shot down, while 25 more were damaged. Dive-bombing and low-flying machine-gun attacks were made in the Harbour and Ratmalana areas. A medical establishment in the suburbs was also hit. (At that time, the press was just as quick as it is today to send out enemy loss figures!!)

Canadian pilots looking on a downed Japanese plane on the 6th April1942

By evening on the 5th April 1942 the entire Colombo city was virtually deserted. Most of the terrified civilian population — including dock workers — fled to the provinces by whatever transport they could find. These included buses, trains, cars, bicycles, rickshaws and bullock carts. Private cars were then far less than now and petrol was rationed under wartime conditions.

So what was the situation in Colombo on April 6, 1942? Let’s start with the places that had been hit.

1. Ratmalana Airport. Mostly small damage on the landing field, only one Airman wounded. The Airfield was fully operational.

2. The Railway works near Ratmalana was hit but still able to function as before.

3. Angoda Mental Hospital, hit by one bomb, several patients were killed or injured in the attack. A medical team was rushed to supplement the staff at the Hospital.

4. Maradana railway station. Was hit by an 800 kg bomb which killed and injured a number of people. The station was partially destroyed, but the rail and switch tracks were intact.

5. Kolonnawa oil installations. One tank hit, burning oil ran out in the associated channel. The fire was extinguished around 21.00 on April 5,1942 (mostly by Ceylonese volunteers who on the spot formed a fire brigade that endured the war.) Other damage to the installations was quickly repaired.

Canadian soldiers with the remains of a Val near Ratmalana

6. Colombo Harbour. 3 ships destroyed, of which 1 ship burned heavily.

Warehouses were hit but the damage was not so extensive as first assumed. Some were killed and wounded, but the port was still operational. Navy engineers together with the Army Royal Engineers were in full swing after the attack, dismantling 5 Japanese bombs which had not gone off. No cranes had been damaged. The clean-up of most of the ports in the area was over on April 6, 1942. However, some of the buildings were damaged (you can still see some of the damage from that time even today).

7. Two of the Royal Navy’s cruisers were sunk with heavy loss of human life.

8. The Royal Air Force had lost about half of that fighter force so there was not much to defend with if a new attack were to come.

9. A Japanese force was on the loose in the Bay of Bengal, and was it turning towards Ceylon?

What was so positive for Admiral Layton and his staff?

1. Ratmalana Airport was operational so that aircraft reinforcements could reach it.

2. Colombo Racecourse Airfield was not hit, and it was the same in Trincomalee and Koggala.

3. The communication between the various units and authorities had failed before/during the attack and these were immediately rectified so that the warning system came to full strength.

4. Ammunition supplies were plentiful, so that if an invasion occurred, the lines for re-supplying the army’s units were short.

5. The civil defence was in place and functioning very satisfactorily thanks to Sir Oliver Ernest Goonetilleke.

6. After the long wait for the Japanese attack, all units were completely up and everyone knew that more attacks would or could follow. All units were in their operational locations, ready to withstand attacks.

7. Layton now knew that there were only 3 options for the Japanese. 1. Attacks on Colombo and Trincomalee. 2. A new head-on attack on Trincomalee. 3 the most feared (but a huge option), an invasion on the south/east coast.

8. Layton was also aware that the Japanese naval force could not continue to attack Ceylon and that in the foreseeable future they would face major problems in supplying the navy with fuel and ammunition.

40 mm Bofors AA gun on the move

9. It should be mentioned here that Layton also knew (from Somerville) that the Royal Navy aircraft have had visual contact with the Japanese navy, but lost the contact

10. At night time on the 6 April 1942 Layton knew that Ceylon was alone. The Navy had gone to the Maldives but all other ships in the waters of Ceylon were safe for the moment. Up north in Jaffna area a lot of merchant ships were at anchor, ready to offload. So the first round of the battle was not that bad.

11. The whole Staff of the defence of Ceylon was now reading all information that SIGINT could come up with and they knew that the Japanese force had to try to take a strong base like Trincomalee out, so it was only a matter of time.

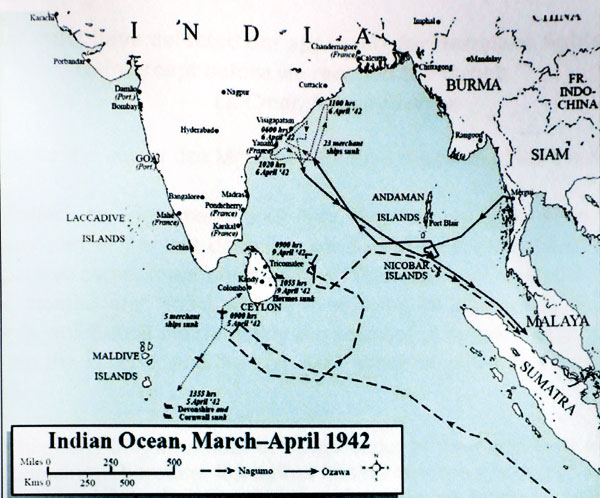

By now Admiral Somerville had learnt of the second Japanese raiding force roaming the Bay of Bengal. Signals were reporting merchant ships were under attack by Japanese aircraft or surface ships were coming in, and fast. In all, Vice Admiral Ozawa’s cruisers and destroyers had at that time sunk 23 ships so more than 100,000 tons was at the bottom of the Bay.

Admirals Layton and Somerville had learnt of the size of the forces that the Japanese navy had in their area of operations. Flights of Swordfish and Catalinas were sent out from China Bay and Malay Cove in Trincomalee to search for the Japanese force.

Several of 273 Squadron Fulmars were flying as escorts, or on reconnaissance flights on their own. But they did not find a single Japanese ship.

Admiral Nagumo, however, had failed to extrapolate the course of the two British cruisers his aircraft had sunk on the 5th April and had totally neglected to send scouting planes out along their line of advance. If he had done so and had they found Somerville ‘s force the outcome of the battle would have been different. That mistake saved the British fleet and probably Ceylon and India. Looking at the situation from the Japanese side, one can easily be led to believe that the British navy was in the area around Trincomalee, and not on its way to the secret base in the Maldives.

So after the attack, the Japanese fleet sailed southeast of Ceylon to rendezvous with an oil tanker and its support ships before launching an air strike on Trincomalee and turn north and keep a distance from the island, as they did not know how many aircraft the RAF had available and that the British carriers could also be a danger to their ships.

Both Somerville and the general staff at Colombo believed by now the Japanese carriers could be headed towards Addu Atoll. Somerville resolved to maintain an easterly course to place himself between the Japanese fleet and their home ports.

After some 26 hours in the water, at 5pm, help finally arrived for the survivors of HMS Cornwall and Dorsetshire. An aircraft flew overhead, signaling “Hold on. Help is Coming”. Then, at 6pm, the light cruiser HMS Enterprise and the destroyers Paladin and Panther hauled over the horizon. Fighters from HMS Formidable and Indomitable maintained a watchful presence. In all 1,122 men were pulled from the water. The two heavy cruisers had been carrying 1546 between them. That evening Somerville’s radar-equipped biplanes of 827 Squadron continued to scout the ocean for any echoes of the Japanese ships. One was engaged by what it thought to be Zeros, but escaped into cloud. It may have encountered an opposing search patrol of D3As.

But Nagumo had slipped the net.

Survivors from HMS Dorsetshire in the water. 6 April 1942.

By April 5, 1942,569 persons lost their lives due to the Japanese attack. The final figure will never be known due to the fact that many who was wounded died later in the days that came.

All military personnel knew that it was only a matter of time before the Japanese fleet struck again on targets in Ceylon, but again the big question was where? But as things looked at that time with today’s glasses, they were ready, and wanted to fight.

Since the Japanese threat arose, RAF Group 222 had been busy, its Chief fortunately foresaw how the Japanese would attack. But on the east coast of Ceylon, he faced a problem in late March 1942. There was only one airfield there and that was China Bay. From the experience of the Battle of Britain (of which he was a participant before being sent to Ceylon), he had already learned that an enemy would go after any airfield and thus try to achieve full air superiority over Ceylon. Once this was created he knew that the Japanese would go after all maritime traffic to be able to eventually be able to deploy a landing force. And this was also the Japanese tactic when they conquered Malaysia, Indonesia, and pretty much the rest of the Western Pacific.

At Kokkilai, 261 Squadron had been deployed since 5 April from China Bay and on 8 April other planes arrived at the satellite station. One would not risk a repeat of the situation at Ratmalana.

On 9 April the following aircraft were based at Kokkilai:

The 12 Swordfish of Hermes’ 814 Squadron

At least six of 261 Squadron’s Hurricanes

Most (12?) of 273 Squadron’s 16 Fulmars

Maybe a Seal and/or a Vildebeest

261 Sqn Kokkilai, Hurricane II. The plane saw action on 9 April 1942. It force landed at China Bay after being damaged by A6M2 Zeroes

On the 6 April 1942 1400-1425 hrs, Fl. Sgt Quinn from 261 Sqdn together with four other Hurricanes flew to Kokkilai to relieve aircraft there. On landing F/Sgt Quinn overshot and ran into trees at the end of the landing strip. The aircraft was later repaired and flew again. Quinn got badly wounded and he died next day in a Seal aircraft of 273 Squadron that was flying him out of Kokkilai. The aircraft struck a Swordfish during takeoff. WO John James Griffin (who was a Battle of Britain veteran) and FIt. Lt. JC Anstie were also killed in the accident.

April the 7th, 1942

At the conference aboard the flagship, Somerville explained how he was convinced of the undesirability of operating his battle fleet, which lacked speed, endurance and AA gun power in Ceylon waters in the face of such superior Japanese naval and air power.

-David Thomas, Japan’s War at Sea

To supplement the battered Catalina patrols, five 11 Squadron Blenheims set out from Colombo to find the Japanese fleet. Several flights of Swordfish did likewise from Trincomalee — again escorted by Fulmars. None found a thing. Meanwhile, the main Japanese fleet had met up with its tankers for an underway replenishment. The carrier air groups rested as mechanics strove to restore as many as possible to service. Admiral Somerville woke to news — a convoy of six merchant ships had been sunk off the coast of India. Another had been bombed by aircraft from Ryujo. Facilities along the east coast of India were being bombarded by Ozawa’s cruisers. But the British were not out of hot water yet. Nagumo was about to launch a second attack, this time on Trincomalee.

Winston Churchill had, by this time, received a report on the April 5 fight. He sent a signal to US President Roosevelt:

According to our information, five, and possibly six, Japanese battleships, and certainly five aircraft-carriers, are operating in the Indian Ocean. We cannot of course make head against this force, especially if it is concentrated. Even after the heavy losses inflicted on the enemy’s aircraft in their attack on Colombo, we cannot feel sure that our two carriers would beat the four Japanese carriers concentrated south of Ceylon. The situation is therefore one of grave anxiety.”

In Colombo, all defence systems were up and operating at full strength. Machine guns were set up by the Ceylon Light Infantry in and around the port in addition to AA units that were in position there. Many of Colombo’s citizens had fled or left the city in fear that a new attack would take place. But the entire Civil Defence system persevered and remained calm like the rest of the forces there. Coast watchers a little north of Galle reported seeing a submarine close to the coast but it has never been confirmed whether it was a Japanese or a British.

In the Trincomalee area, an attack was still being prepared and the various Commanders kept their units running at all times. All leave was prohibited and all units were kept in their operational place. The RAF 990 Barrage Balloon Squadron was in full swing with all available men unloading the ship that had brought all their equipment to Ceylon. This was a long lap, however, but as soon as they had equipment ashore, it was driven directly to the places where it was needed.

In the harbour everything was quiet and calm, only a few ships were there and all ready for battle. Some forces from the Ceylon Defence Force were stationed south of the harbour during the day to counter an invading force.

April the 8th, 1942

At 11am, the Eastern Fleet pulled into Addu Atoll. An urgently convened conference of captains was told by Somerville that he no longer held any intention of attempting to intercept the Japanese.

The loss of HMS Dorsetshire and Cornwall had put a serious dent in his fast force. And the overwhelming strength of the Japanese carrier air fleet made the force aboard Formidable and Indomitable seem almost irrelevant. Instead, Somerville would ensure a ‘fleet in being’ by sending Force B westwards, to the Kilindini naval base near Mombasa. Force A set course for Bombay. From here it could continue to deter Japanese attacks on convoys operating in the Indian Ocean. But it was far enough away to evade any attack from a heavy carrier force. The crews of the Eastern Fleet were shattered. Why were they running away?

However, when informed, Churchill approved:

“On one point we were all agreed, the RN should get out of danger at the earliest moment. When I put this to the First Sea Lord there was no need for argument. Orders were sent accordingly”.

The Japanese carriers, having completed their replenishment, turned to the North West. They were to launch an attack on Trincomalee at dawn the next day.

Again, the Catalinas of 240 Squadron — this time piloted by Flying Officer Round — made a timely sighting. Nagumo’s force was detected early in the morning when some 500 miles east of Dondra Head at the southern tip of Ceylon. With enemy fighters approaching, Round was able to hide his big flying boat among cloud — returning to the lagoon late in the evening.

The Commander-in-Chief of Ceylon, Admiral Layton, immediately deduced Trincomalee was in for an attack. He put the island’s defences on full alert again. All ships in Trincomalee harbour were ordered to sea, but the 15-inch gunned Erebus remained to supplement the defences. One cargo ship, the Sagaing, was unable to set sail.

Among those to leave was the light aircraft carrier HMS Hermes, commanded by Captain Richard Onslow. The 10,850-ton carrier prototype from 1923 could only carry 15 aircraft. But in the same manner as the escort carriers just beginning to enter service, she had been provided valuable anti-submarine escort services to shipping in the western Indian Ocean. She was in Ceylon to prepare to join the fleet carriers in their attack on Madagascar in May. Hermes, which had by now been back in harbour for four days, was not able to get underway immediately. The boiler cleaning work had to be made good and her liberty men recalled from shore.

Only two Swordfish — both undergoing repair — were in the hangar. The remaining 12 aircraft of 814 Squadron were nesting in China Bay.

At 7 pm, Captain Onslow took his ship, accompanied by the elderly Australian destroyer HMAS Vampire, the corvette Hollyhock, the tanker British Sergeant and the submarine depot ship Athelstone directly south. He hoped that by keeping clear of the coast he would evade Japanese submarine and reconnaissance patrols. In Colombo Port repairs were done but still one ship was on fire (it was for almost 2 weeks). But the Port was 100 percent operational and civilian workers were coming back again. Cleaning up and repairs were done in the areas of attack and great effort was put in by Sir Oliver Ernest Goonetilleke to remove all traces. Maradana railway station was fixed and painted by the use of a huge workforce in less than 3 days. And the glaziers in Colombo had some lucrative days when many windows had to have new glass in them.

At night time all of Ceylon was calm and waiting for the next attack.