Intrepid naturalist and first woman to publish travelogue on Sri Lanka

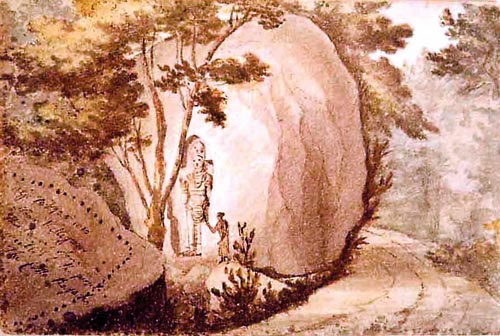

Kustarajagala Weligama 1806

Maria Graham, a popular children’s writer and author of books on travel was the first woman to publish a travelogue on Sri Lanka. A gifted watercolourist of landscapes and botanical subjects with a scientific bent, her reflections were more descriptive and personal. With the passage of time, her landmark contribution to botany and geology has been recognised and respected.

Her book, Journal of Residence in India (1812), also illustrated by her was preceded by only the works of two other writers – James Cordiner (1803) and Robert Percival (1811).

For centuries there prevailed in Britain, a cultural bias against women being admitted to the leading scientific institutions and societies and the number of women still accepted is small in leading institutions in the arts and sciences. Maria Graham underwent a baptism by fire merely because of her desire to be accepted among the 19th century scientists in England as a naturalist with a passion for botany and geology.

It was only in 1945 that the Royal Society (est. 1660) elected the first woman Fellow – microbiologist Kathleen Lonsdale (1903-1971). Girton College, Cambridge, only admitted female students in 1869 and appointed its first female lecturer in 1947.

Almost a century after Maria Graham, other women writers– Margaret Leitch (1890), Constance Gordon Cummings (1892), Marianne North (1893), and Bella Sydney Woolf (1914) would record their observations of the island.

Maria Graham

Maria arrived in Galle on the H.C. cruiser Prince of Wales on February 16, 1810. Her travels were confined to the maritime territories under British control – Colombo, Negombo, Brucella, Galle and Weligama and by March 1810, she had returned to India. Many of her fine series of landscapes and botanical water colour sketches are now at the Herbarium, Kew Gardens, London.

Born in Scotland as Maria Dundas, her father George Dundas (1756-1814), was a senior naval officer. In 1808, Maria, aged 23, sailed with him to Bombay where he was the head of the British East India Company’s naval yard.

While on board she fell in love with a senior naval officer Robert Graham. They married in 1809 and in 1811 returned to England, when her first book, Journal of a Residence in India, was published in 1812. While her husband was away at sea she kept herself busy working as a translator, book editor and illustrator.

By 1819 she toured Italy and published a book of her travels, Three Months Passed in the Mountains East of Rome, in 1819.

She developed a taste in the arts and her next book was on the French baroque artist Nicholas Poussin who was then the rage in European art circles, titled, Memoirs of a Life of Nicholas Poussin (1594-1665).

In 1821 she accompanied her husband on the H.M.S. Doris to Chile. The vessel had rounded the Cape Horn when disaster struck with the death of her husband in April 1822. His fellow officers offered to accompany her back to England, but she rented a cottage in Valparaiso, and plunged into her interest of natural history living among the native Chileans.

On November 19, 1822 she recorded an eyewitness account of one of the world’s most disastrous earthquakes which killed more than 500 of the citizens of Valparaiso and triggered a tsunami.

Maria Graham described the devastating scene; how a hundred mile stretch of coastline had been lifted out several feet above its former level – “the ancient bed of the sea laid bare and dry with beds of oysters, mussels and shells adhering to the rocks on which they grew the fish being dead and exhaling the most offensive effluvia”.

By 1823 she returned to Britain and en-route in Brazil was introduced to the Emperor of Brazil Dom Pedro who made her an offer she could hardly resist; that she should be tutor to his young daughter, princess Donna Maria.

Maria returned to England and took the opportunity to hand over two manuscripts for publications – Journal of a Residence in Chile During the Year 1822, and A Voyage from Chile to Brazil in 1823 and also A Journal of a Voyage to Brazil During Part of the Years 1822-1823, both illustrated by herself.

After collecting the papers necessary to teach the Princess Donna Maria, she returned to Brazil in 1824. Her stay was short. The palace courtiers believing her motive was to anglicize the young princess, successfully conspired to discontinue her duties.

During that short interlude at the palace she developed a close relationship with the Archduchess Maria Leopoldina of Austria who shared her passionate interest in natural history. After facing much opposition from the courtiers, she left Brazil disaffected.

But by a final twist of fate, and largely due the political links between Portugal and Brazil, the pretty little girl she gave lessons to during her sojourn in Brazil ended up ascending the throne as the Queen of Portugal.

Arriving in London, Maria Graham found a suitable residence in Kensington Gravel Pits, south of Nottingham Gate, a sort of artist enclave patronized by Augustus Wall Callcott, a Royal Academy painter and his musician brother John Wall Callcott, and renowned artists John Varley, Edwin Landseer, John Constable and J.M.W. Turner among others.

Maria’s home became a focal point for London’s intellectuals including her publisher John Murray and historian John Palgrave. It was her keen knowledge of the arts and sciences that helped her keep company with such intellects.

Maria soon became involved with Augustus Callcott. They married on February 27, 1827, subsequently travelling extensively in Europe and the Middle East, often accompanied by the eminent painter J.M.W. Turner. After returning from her honeymoon in 1828 she published A Short History of Spain and during her long convalescent period two books including Description of the chapel of Annunziata.

She also published a detailed study of the Islands of Hawaii, including the fatal visit of both the King and Queen of Hawaii to England (they died of an attack of measles).

Tragedy struck the second time in her life in 1831 – she ruptured a blood vessel and soon became an invalid.

The knowledge and outcome of the violent stresses impacted by natural disasters such as earthquakes, volcanic action, tsunami and other events that changed the composition and structure of the natural environment, was still in a formative stage. Her contribution the effects of such a rare event to the earth sciences at a time little was known, was significant.

Later in the 1830s she dispatched a detailed account of her observations and speculation of the after-effects of the Chilean earthquake to Henry Welbourne, the founding father of the Geological Society. This was published in the Transactions of the Geological Society.

Maria Graham’s papers of her observations of the Chilean earthquake (a first-time eye witness account by an English individual), triggered a heated debate within the Geological Society and two rival schools of thought.

Her observations were that the larger area of land rising from the sea in 1830 was an important factor of the formation of the earth’s physical structure. It was of great consequence that Charles Lyell included some of these observations in his groundbreaking work The Principles of Geology, thus shoring up evidence in support of his theory that mountains were bi-products of violent volcanic action and earthquakes.

Three years later in 1835, the succeeding president of the Geological Society George Bellas Greenough decided to attack Lyell’s theory, ridiculing her observations and reports as that of an untrained female.

It came to such a dramatic conflict that her husband and nephew wanted to challenge Greenough to a duel. Maria’s response was characteristic: “Be quiet both of you, I am quite capable of fighting my own battles.”

Thereafter Maria Graham’s published account was supported by one of her admirers – none other than Charles Darwin (1809-1882). When Darwin visited South America during the voyage of the ship H.M.S. Beagle (Dec 1831- Oct 1836), on February 20, 1835, while the Beagle was in the vicinity north of Valparaiso, they experienced a massive earthquake and witnessed a spectacular scene of the volcano emitting from peaks near Mount Osorno. Darwin saw the total destruction of the city of Concepcion and the effects of the massive tsunami and may have possibly recalled Maria Graham’s experience a decade before his own encounter.

The earthquake had done had something profound to the coast-stretches. Land that was under the sea had surfaced with all the debris of dying fish, and Darwin realized that Lyell had provided him with the explanation of what he was witnessing.

Darwin had taken along a copy of Lyell’s work during the voyage of the Beagle. Many of his ideas such as the gradual operation of natural selection and its reliance on immense eons of time were both derived from Lyell.

Among her other interests, Maria Graham was an avid plant collector and illustrator of flowering plants. She was undeniably an important figure in the network of women travellers interested in botany who contributed their findings such as drawings and specimens of plant material to the major botanical gardens in Britain and Europe.

Her time in South America was effectively utilized to collect, specimens, dry and assemble them and make illustrations of exotic plant specimens, unique endemic species unknown tog botanists in England.

Maria Graham shared much her correspondence of her botanical observations and drawings with William Dawson Hooker (1816-1840), Professor of Botany at Glasgow University. Hooker was impressed with her publications on the flora and fauna of Chile, Brazil as well as India and her translation of Judas Tadeo de Reyes’ Account of Useful Trees and Shrubs of Chile. Hooker and other botanists celebrated these contributions as important scientific data.

W.D. Hooker (1816-1840) was a British physician and botanist and son of Sir William Jackson Hooker (1785-1865), the first Director of Kew Gardens and an elder brother of Sir Joseph Dalton Hooker. Both botanists, father and son created the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, as the foremost botanical institution in the world. The latter Dalton Hooker was a friend and mentor of Charles Darwin.

Though unfairly treated by her male counterparts in England in the 19th century and often referred to as merely a highly accomplished Englishwoman rather than recognised for her contribution to botany or geology in her own right, Maria Graham is now respected for her sterling contributions as a plant collector and to geological studies of the nineteenth century.

Searching for an ideal partner? Find your soul mate on Hitad.lk, Sri Lanka's favourite marriage proposals page. With Hitad.lk matrimonial advertisements you have access to thousands of ads from potential suitors who are looking for someone just like you.