Lankan born British swimmer, David Wilkie, passes away

David Wilkie was born here in 1954

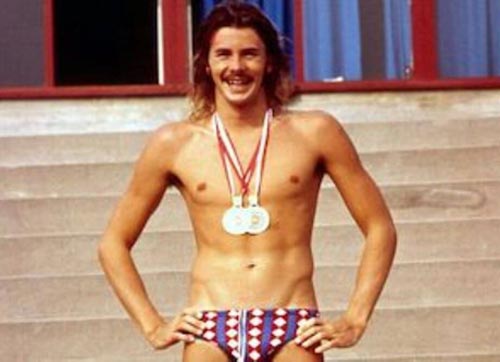

On the day that David Wilkie, who has died of cancer aged 70, won an Olympic swimming gold medal in Montreal in 1976, he was the first British man to do so since Henry Taylor 68 years earlier. Expectations for him were high: as a teenager, he had won Olympic silver for the 200m breaststroke in Munich in 1972, and the following year became world champion. In Montreal he delivered, beating the world record in the same event by three seconds – a country mile by swimming standards.

In his second Olympics he had hoped to target three gold medals, confident from his two 1975 world championship golds, his No 1 world ranking in both the 200m breaststroke and 200m individual medley, and his world No 2 status in the 100m breaststroke. However, the 200m individual medley was taken out of the Olympic programme in 1976, and Wilkie’s US rival, John Hencken, came first in the 100m breaststroke, with Wilkie settling for silver before achieving his gold medal triumph.

Aged just 22, he then retired with five world records, 23 Commonwealth records, 16 European records and 30 British records to his name. In 1977 he was appointed MBE, and five years later was inducted into the International Swimming Hall of Fame. His idea on retiring was to explore the commercial possibilities of providing swimming aids.

It was Wilkie who introduced the use of a hat and goggles while swimming. At the time they were considered artificial enhancements, with one official at an event in Canada telling him he could not wear a hat, on the grounds that it broke amateur laws.

As he said in an interview shortly before the Rio Olympics in 2016:

“I tried to be a bit of a rebel and grow my hair long, and I hated that chlorine got in my eyes. It worked for me and it became, I suppose, de rigueur for swimmers from that day on.”

In the 90s, he worked with the swimwear brand Speedo to develop the “speedmask” with goggles built into the swim hat, but it failed to catch on. As a swimmer, it was quite clear to him that “success is usually only measured by the amount of gold medals you win … no one remembers the guy who won the silver or the bronze medal.”

But continuing at that level at the next Olympics, in 1980, was not open to him: “In those days I could not have swum in Moscow because I was classed as a professional swimmer. Had I won in Moscow with the times I had done in Montreal, I would have won three gold medals. In those amateur days you were restricted to how many Olympics you could do if you made money out of your past glory.”

Born in Sri Lanka in 1954, David was the son of Scottish parents, Jean and Harry Wilkie. His father, who ran a tea plantation, was very keen on sport, and the family were members of various swimming, golf and tennis clubs.

David reflected: “Maybe I wish I had taken to tennis more naturally, but I had been swimming a long, long time, so by the time I got back to Scotland from aged 11, I was a good swimmer.”

On their arrival in Edinburgh, his father sent him to the independent school Daniel Stewart’s college (now Stewart’s Melville College) and signed him up for Warrender Swimming Baths club. David hated training and could not understand the discipline, finding it tedious. At the age of 15 his coach threatened to kick him out of the club; the 1970 Commonwealth Games were held in Edinburgh and this rebuke spurred him on to win a bronze medal for Scotland at the age of 16.

By the time of the buildup to his first Olympics, two years later, he was ranked 36th in the world, but with a reputation for avoiding

hard work. His apparent lack of commitment made his silver medal a surprise to many, but he had done enough to impress in the US, with the offer of scholarships at Harvard and other universities.

He accepted a place at the University of Miami, where he studied marine biology while training for the next Olympics. As he later admitted, had he not made the move from Edinburgh he would probably not have gone on to win Olympic gold. Though based in the US, Wilkie became the one to break the American swimmers’ dominance of the sport, and the clean sweep of medals that they might have expected in Montreal.

“I was looked upon as an American that was swimming for Britain, because I spent four years in America. I was funded by them so they really thought I was a phoney Brit.” He went on to develop business interests beyond swimming, in 1986 co-founding the healthcare company Health Perception, which in 2004 was sold for £7.8m. Then he co-founded Pet’s Kitchen, a pet food company supplying British supermarkets.

In this respect he was something of a pioneer in building a career that went beyond sporting success while young: “I think I was one of the first commercial athletes to make that change from sport into commercial life; writing books, working with television companies, opening up swimming pools, doing talks. It was an eye-opener for me, because it was a change in amateur sport. In ’76 that breakdown started to happen between amateurism and professionalism.”

In 1985 he married Helen

Isacson, from Sweden. She and their two children, Natasha and Adam, survive him.

– The Guardian