News

Tea estates condemn workers to sub-human lives, tribunal testimonies show

The performance-based pay system on many plantations is a major part of the problem, says the tribunal. (file pic)

“I wanted to express my struggles somewhere,” said a plantation worker who testified at a workers’ tribunal on exploitation in the sector. “There has been no solution for years.”

The tribunal is a symbolic one, organised by the Ceylon Workers Red Flag Union and presided over by three retired justices from Sri Lanka, India, and Nepal. Frustrated with the lack of progress for over 200 years, the tribunal aimed to collect testimonies and pass at least a token judgment.

The judges—A.P. Shah, the former chief justice of the Delhi High Court; Shiranee Tilakawardane, a former Supreme Court judge; and Pawan Kumar Ojha, a former judge of the Supreme Court of Nepal—said the testimonies of the 11 workers “shocked our collective conscience’’.

The tribunal used Sri Lankan law, international law, and historic precedents from around the world in their judgment.

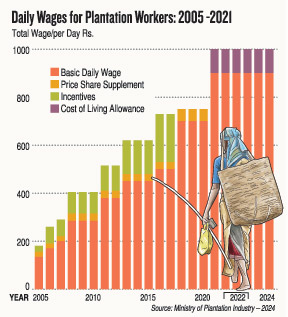

They found that many workers took home less than the minimum wage.

In a strong statement, the tribunal found this to be akin to “forced labour”, and further said that the condition of plantation workers “reduces them to bonded labour’’. The performance-based pay system on many plantations is a major part of the problem.

One worker recounted how 20 kilograms of tea leaves have to be picked to earn Rs. 1,000, but because this is not possible during certain seasons, some days they take home only Rs. 700. Plantation companies also offer fewer working days to avoid paying the minimum wage, she said.

The tribunal also found there to be a “lack of fundamental living standards and working conditions, especially for women,” and a “blatant disregard for occupational health and safety.” Many plantation workers live in line rooms, some of which were built by the British more than 100 years ago. These are tiny rooms where entire families live with no privacy and often no sanitary facilities. Work provides no escape, as painful living conditions are repeated on the job.

Speaking to the Sunday Times, a worker explained how she eats her lunch at work: “On the floor where the dogs urinate, the ants crawl, and the leeches bite.”

Another worker said that unlike before, forest cover is spreading in many plantations, and creatures including snakes and wild boar are increasingly common.

“We have had to run away from animals while working, but the plantation company doesn’t do anything about the overgrowth,” said a rubber plantation worker.

The lack of protections for workers stems in part from the casualisation of their work, whereby many estate staff are not registered but rather hired as daily wage workers without guarantee of working days and income.

The tribunal found that this system deprived workers of “protection from unlawful termination, compensation for injuries at the workplace, retirement benefits such as provident funds and gratuity, maternity benefits, as well as the right to unionise and engage in collective action.”

Menaka Kandasamy, an advisor for the Red Flag Union, said that a key issue is the end of the collective agreement, which stipulates wages and other conditions for work between unions and employers, in 2019. “Normally, if there is no collective agreement in place, it’s the government’s duty to get involved to protect the worker. They are failing to do this.”

People’s tribunals, such as this one, have been practised around the world, often in instances where real justice seemed unlikely. For instance, the Russell Tribunal addressed the United States’ aggression towards Vietnam, and the Comfort Women Tribunal passed judgment on sexual violence committed by Japanese soldiers during World War Two.

Plantation workers, too, have had little luck in seeking justice.

Plantation workers, too, have had little luck in seeking justice.

Labour tribunals take years to pass judgment and provide relief. Officials from the Badulla, Hatton and Thalawakelle Labour Tribunal said most cases take anywhere from two to five years.

“We have been complaining to the big unions, but they didn’t advocate for us,” said a worker, describing her frustration. “We complained to the Labour Department, and then too, we got nothing. So that’s why we organised this for justice.”

The organisers said the next step would be to join with other unions and push for the recommendations made by the tribunal. Among the many recommendations, the tribunal suggested that Sri Lanka implement a law specifically for plantations, as in neighbouring countries, stipulating minimum working standards.

The best way to say that you found the home of your dreams is by finding it on Hitad.lk. We have listings for apartments for sale or rent in Sri Lanka, no matter what locale you're looking for! Whether you live in Colombo, Galle, Kandy, Matara, Jaffna and more - we've got them all!