Diverse voices out of Sri Lanka

View(s):In this email interview with Adilah Ismail, the editors behind a new anthology of poetry share their lengthy process and many challenges in bringing it together

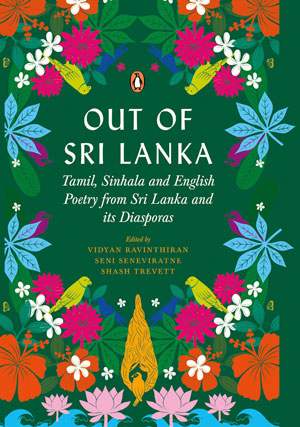

Out of Sri Lanka is the first ever anthology to bring together Sri Lankan and diasporic poetry. Published in 2023 in India and the UK, it features diverse poems of a mix of styles, place and time. Largely concentrating on poetry published after Sri Lanka’s independence, Out of Sri Lanka highlights poetry in English as well as Sinhala and Tamil poetry translated into English, by established and new poets in and out of Sri Lanka.

- Vidyan Ravinthiran

- Shash Trevett

- Seni Seneviratne. Pic courtesy Sam Hardwick@Ledburypoetry

The anthology features poems by 138 poets and 38 translators. A notable feature in the anthology is the diversity of poets and themes covered — both well-known names and up-and-coming poets share space in the anthology writing about love, loss, memory, the tsunami, insurrection, racism, cultural cadences, the immigrant experience, bearing witness to the civil war and more. Out of Sri Lanka features work by Packiyanathan Ahilan, Anar, Michael Ondaatje, Vivimarie Vanderpoorten, Vihanga Perera, M.A. Nuhman, Ramya Chamalie Jirasinghe, Mahagama Sekera, Alfreda de Silva, George Keyt, Avvai, Megan Dhakshini, Tashyana Handy, Imaad Majeed and more. Further, the anthology recovers poems from archives long out of print while a call was also put out for submissions to encourage and feature new poems. Some poems in the anthology have never been published before.

“Yet the time is right — the moment is now — for the world to know Sri Lanka better: its beauty and pain,” notes the anthology’s introduction, locating the book in the context of the civil war, Easter attacks, the pandemic and the 2022 protests while acknowledging and challenging the complexities of poetries of the Global South and postcolonial poetry.

A project in the works for three years, the anthology is edited by Vidyan Ravinthiran, Seni Seneviratne and Shash Trevett. Below are excerpts from an email Q&A with the editors by the Sunday Times.

n Something I enjoyed was the diversity of poets and poems featured in the anthology. What was the process of obtaining, selecting, structuring and organizing the poets/poems in the anthology? Could you describe some of the work that went into the process and how long this took?

Vidyan: One of my tasks was to track down Anglophone poetry, much of it hard to access and often out of print. Library loans helped with this. Also, Sri Lankan literary magazines archived either in libraries or online. One important decision we made was to arrange the poems in the book alphabetically, instead of siloing Sinhala, Tamil and English poetries. Sri Lanka has been a country divided, and we wanted to put these works in conversation.

Shash: Putting together this anthology, from start to finish, was one of the most pleasurable and affirming things I have done, mainly because Vidyan and Seni are such wonderful poets (and people) to work with. We nominally split the workload based on our own spheres of expertise: Vidyan sourced and collated the Anglophone poetry, Seni concentrated on the Sinhala and I looked after the Tamil side.

It took a lot of reading! We had just begun talking about the scope of the book when we hit lockdown. Suddenly we had the time to read and digest material at leisure. We began with the poets: we read anthologies, journals with a special focus on Sri Lankan poetry, individual collections by poets, academic articles on the politics and poetics of Tamil and Sinhala poetry, all the while noting down names that kept cropping up. Soon we had embryonic lists – one for each of the three languages – which we sent to poet and academic contacts we had, asking them to add any names we had overlooked. From there we began to search for the poems themselves. Our original lists were enormous!

Seni: We also decided at an early stage to organise a call-out for submissions from previously unpublished poets or those less well known. This involved reaching out to contacts in Sri Lanka and elsewhere and soon we started receiving some wonderful poems from poets we had not previously heard of. At times we entered into dialogue/mentoring relationships with poets in order to help them bring out the best in the work they had submitted.

n What were the challenges you faced when putting together and publishing Out of Sri Lanka?

Vidyan: There is, now, a welcome emphasis on racial, and other forms of diversity, in poetry publishing. But this usually means, people of colour writing in the UK and the US. There’s also a problem on the academic side, where postcolonial scholars tend to focus on fiction, not poetry. Reading lists rarely feature any poets from the Global South other than Derek Walcott.

One reason I took the job at Harvard – even though it meant leaving a permanent job in the UK, for an untenured post – is because I knew we’d need Harvard’s clout, both esteem-wise and money-wise, to get this done. We also needed the support of a publisher who could think in terms of literary history, and see beyond today’s trends. As far as I’m concerned, Neil Astley at Bloodaxe is a hero for doing this.

Shash: One of the biggest challenges we faced was getting hold of texts. Much of the poetry published in Sri Lanka had never made it out of the country, had had a small print run, or had been privately printed. These books had vanished from the public sphere and were mostly held in the private libraries of other poets or family members. As none of us are based in Sri Lanka, we had to build up networks of connections with poets and academics there who could access these books for us. On top of this, the pandemic brought to a halt the inter library loan service at Harvard, which we had wanted to use to get hold of books.

When it came to translating Tamil poetry, I met a similar problem. Publishing houses had gone out of business, poets had died. It is almost impossible to get hold of Tamil texts in the U.K. But many people were generous with their time. They put us in touch with family members who could give permission for us to publish new translations of poems. Others sent us scanned pages from their libraries.

Some of the hardest conversations we had were to do with the translations: do we include the work of a major poet poorly translated, or do we leave the poet out? In some instances, we decided not to include a well-known poet because we didn’t feel the translations did them justice. Sometimes we approached the translator and asked whether they would accept editorial suggestions: in most cases translators were happy to work with us. In some cases, they weren’t, and we were not able to include their work.

Seni: I agree with Shash that getting hold of texts was one of the hardest things. There were also difficult decisions to make about some of the submitted poems that we didn’t think were ready for publication. As Shash said earlier the poems and the quality of the poems was the main focus so although it was hard to say no to some of the work it was also necessary. And also when it came to trying to contact some of the published poets for biogs and permissions that presented another challenge.

n All of you come from a background in poetry, are based in the UK and US and are of Sri Lankan heritage. There is a brief allusion in the book’s introduction about recognizing the complexities of applying Anglo-American literary standards to global literature, both as anthologists and Sri Lankan poets immersed in the process of selecting and discarding work for this anthology. Could you speak a little about this, please and how you navigated this?

Vidyan: Aesthetic standards vary. But all poets want their poems to read as works of art—even when they are writing, as Tamil poets often are, a poetry of witness. We cannot go on, say, reading Robert Lowell for his beautiful phrasing, while never giving the same level of attention to poets from the Global South. It’s patronizing.

Shash: We were not interested in perpetuating an old, or creating a new, cannon. We wanted each poem to have earned its place in the book, regardless of who had written it or had translated it. The strength of the poem itself was of paramount importance to us, recognising of course, the biases and influences that coloured our own judgement. ‘What makes a good poem’ is a conversation poets can spend weeks arguing over! We recognized the particular stylistics of poetry from Sri Lanka, whether in English or in translation. For example, a slightly formal, stilted style used by older poets who were writing during, and just after, Independence in 1948. Or the difference in form and structure used by Tamil and Sinhala poets which bled through into the translations: for example very short, 5 syllable lines which led to long, thin poems on the page, something which is (traditionally) alien to English poetics in the West.

n What were the biggest surprises you encountered while working on this project?

Shash: I think one should always be surprised by a good poem. That is one of the joys of life: to begin reading something and to have the poet open new vistas to you. I think we were all often delighted by what we read, sometimes sobered, sometimes upset. Almost every poem we included in the book evinced some sort of reaction from us and we hope that they will similarly strike the reader.

Along with shining a light on neglected and forgotten works, we were committed to publishing work by new and unknown poets. We put out a call for submissions and used literature organisations across the world to spread the word. We received many, many submissions and discovered young poets who, in a post-war Sri Lanka, were forging their own paths: tackling corruption, dislocation, sexual and identity politics alongside age old preoccupations with family life or love. These new voices were ones we were keen to champion as they were the future of the country.

Many young poets were writing in interesting ways: merging Sinhala, Tamil and English to forge a poetics which sought to break down barriers. They were iconoclasts in their own way, wishing to dismantle the ever-present strangleholds of privilege and patriarchy which still holds the country in sway. We found spoken word poets and fell in love with their energy; we found young women refusing to give legitimacy to sexual politics. Poets from the diaspora were writing about the effects of second generational trauma so powerfully, we wanted readers in Sri Lanka to have the chance to read them. All these poets played with form and imagery in exciting ways and we were so privileged to be able to include them in our book.

Out of Sri Lanka is available at

leading bookshops

Searching for an ideal partner? Find your soul mate on Hitad.lk, Sri Lanka's favourite marriage proposals page. With Hitad.lk matrimonial advertisements you have access to thousands of ads from potential suitors who are looking for someone just like you.