News

Aggressive poachers challenge Sri Lankan naval intercepts

View(s):By Tharushi Weerasinghe

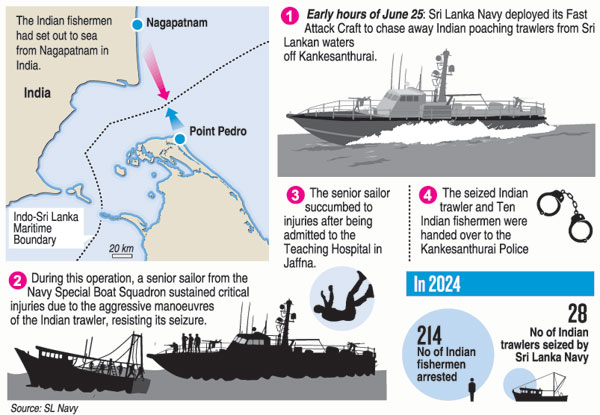

Ten Indian fishermen detained by the Sri Lankan Navy for poaching will be charged with the death of a sailor belonging to the Special Boat Squadron. He sustained critical injuries to his spine resulting from the “aggressive manoeuvres” of the Indian trawler that was resisting arrest. He died at the Jaffna Teaching Hospital last week.

This operation was the latest in a spate of arrests for trespassing this year, as the navy has apprehended 214 fishermen and 28 boats since January.

According to the Sri Lankan Ministry of Fisheries, 500 Indian bottom trawlers enter Sri Lankan waters daily, each hauling in about 1,000 kilos of fish and prawns from the northern waters. The estimated daily loss is Rs. 350 million.

The highly sought-after marine resources of Sri Lanka’s northern waters have been at the centre of a decades-long dispute between local northern fishermen and South Indian fishermen. The territories are clear, but tradition and rich resources continue to attract Indian trawlers.

“We go where the fish go,” said P. Sesu Raja, president of the Rameswaram Fishermen’s Association. He has been a vocal advocate of the expansion of south Indian fishermen’s territories and critical of the Sri Lankan Navy’s use of force against Indian poaching. A common claim from South Indian fishermen is that the SL Navy routinely targets smaller fishing boats instead of trawlers.

The SL Navy vehemently denies this. “Ninety percent of the arrests and seizures this year alone have been of bottom trawlers,” said Navy Spokesperson Captain Gayan Wickremasuriya. Bottom trawling was banned in Sri Lanka in 2017 due to the devastating impacts it has on marine ecosystems, but it is still legal and heavily practised in India.

According to the spokesperson, over 500 trawlers sail three times a week from “Baththalangunduwa to Point Pedro,” and the Navy does not have the resources to apprehend every vessel. “Their boats have steel hulls, which makes them more difficult to approach in rough seas since our hulls are made of aluminium and fibre.”

The trawlers aggressively manoeuvre and use other tactics to avoid seizure.

“They throw hot water and broken glass or try to take hostages—anything to avoid being captured,” the spokesperson told the Sunday Times. He noted that, given the volume of boats and complexity of the equipment at play, chasing trawlers back to India was often easier than seizing them.

Cpt. Wickremasuriya also claimed that some Indian fishermen were even destroying the equipment of local vessels. Northern Sri Lankan fishermen still use less advanced equipment with small capacities because fishing in northern waters was prohibited during the war.

Excess capacity is a major factor behind continued poaching by Indian fishermen, according to experts. “While it is a contributing factor, the belief in a traditional right to fish is one held by the fishermen on the Indian side of Palk Bay, not the entirety of Tamil Nadu (TN),” said V. Vivekanandan, Secretary of the Kochi-based Fisheries Management Resource Centre. He asserts that excess fishing capacity linked to the “historical right to fish” and strong public support in Tamil Nadu are the real roots of this persistent issue.

During Sri Lanka’s civil war, local fishing declined due to restrictions, while the TN trawler fleet expanded. Despite efforts by the Sri Lankan Navy to restrict access, TN trawlers continued to encroach on Sri Lankan territorial waters. Notably, Sri Lankan fishermen in the Mandapam refugee camp were permitted to fish on Indian vessels, inadvertently supporting the Indian trawlers.

The Tamil Nadu fishermen being taken to courts to face charges over the killing of a Sri Lankan sailor

Mr. Vivekanandan described how the excess capacity of Indian trawlers from Palk Bay is the root cause of continued incursions into Sri Lankan waters.

“Ironically, this capacity has only grown since the civil war ended in 2009, primarily due to the increase in the size and horsepower of individual trawlers rather than their overall number,” he claimed.

In Nagapattinam, post-tsunami rehabilitation replaced old wooden trawlers with large steel boats operating along

Sri Lanka’s northern coast. In Rameswaram, this escalation aimed to counter intensified Sri Lankan Navy patrols. “Larger and more powerful boats from Tuticorin facilitated swift incursions into Sri Lankan waters during patrol breaks, yielding substantial catches.”

Before the war, the northern fishing industry contributed to 1/3 of Sri Lanka’s fisheries earnings, but this has severely deteriorated. Sri Lankan fishermen from the north still use plastic-fibre boats. Indian trawlers, on the other hand, have GPS scanners that can locate pools of fish. Fifteen years after the war, the northern fishermen of Sri Lanka have not received any meaningful empowerment from the state.

Kumari Somarathna, secretary to the Ministry of Fisheries in Sri Lanka, held that an allocation of Rs. 500 million was made from the budget. “The honourable minister himself is from the north, and the Rs. 500 million allocated in the budget is for such development projects as lagoon development and sea cucumber farming projects, exclusively for the northern fishermen,” she noted.

Nonetheless, government support remains extremely elementary in comparison to the kind of support the fishermen need. Documents obtained by the Sunday Times revealed that all the proposed projects for 2024 remain limited to short-term assistance like the provision of nets and rice, while the resolution of the longer-standing issues like the bottom trawlers would help the fishermen in the long run by cutting the issue out at the root.

Ms. Somarathna refused to comment on the geopolitical resolutions to trawling that are the need of the hour. “I am not the authority to comment on this; the minister is.”

However, the local delegation to the India-Sri Lanka Joint Working Group on Fisheries, which oversees diplomatic discussions, is usually led by the Secretary to the Ministry of Fisheries. It last met in March 2022. A sixth meeting was proposed for November or December last year, but it did not materialise due to internal issues in Sri Lanka.

Last March, the Chennai High Court, in the case Fisherman Care v. Union of India, ordered the deputy solicitor general to inquire about the possibility of convening the working group to bring a lasting resolution.

Ms. Somarathna confirmed that no such meeting had been slated.

“I established a committee with some lecturers from the University of Jaffna, the Navy, and other stakeholders because the sectoral oversight committee has asked for a report.”

Geopolitics experts like diplomatic historian George Cooke have pointed out a double standard in the Indian government’s approach. While noting that they have always championed the political rights of Sri Lanka’s Tamil community, the deprivation of their economic rights in this case was problematic.

“The fishermen in the north are from the Tamil community of Sri Lanka, and this is their primary livelihood; so they are the ones directly affected when Indian trawlers choose to keep poaching.”

He noted the injustice in the fact that Indian fishermen have significantly more space to fish in but continue to encroach, against which Sri Lanka’s struggling northern fisheries cannot compete. “There must be no bullying,” he said.

| Indian fishermen remanded till July 8By N. Lohathayalan Ten Indian fishermen arrested over the incident leading to the death of a Sri Lankan Navy sailor off Kankesanthurai have been remanded until July 8 on an order by the Mallakam Magistrate. The incident occurred when the Navy tried to arrest the Indian fishermen who were engaged in cross-border fishing in the Kankensanthurai waters. The navy had arrested the 10 fishermen and handed them over to the Kankesanthurai police, where their statements were recorded. A medical examination of the fishermen was carried out at the Jaffna Teaching Hospital before they were produced before the magistrate. They were charged with trespassing into Sri Lankan territorial waters and recklessly piloting their boat, causing the death of the sailor. Bottom trawling turns ocean into graveyard Bottom trawling is a fishing method that scrapes the whole bottom of the seabed to extract economically viable species. “From an environmental perspective, it is totally devastating to coastal and shallow water ecosystems, so fish resources will die out because seagrass and corals, which are the cradles of marine biodiversity, will all be uprooted,” said Dr. Terney Pradeep Kumara, a senior lecturer on oceanography at the University of Ruhuna, Sri Lanka. The depth of the sea in Palk Bay and the Gulf of Mannar is between 12 and 14 metres, and those areas are fragile ecosystems covered in seagrass and coral patches. “When you remove them, you remove the base of the food pyramid, so not only are you destroying the species, you’re also destroying regeneration.” Bottom trawling also changes ocean dynamics by re-suspending bottom sediment and lowering light levels in the water. This reduces photosynthesis in ocean-dwelling plants and carbon absorption, making the water toxic. “Its continued use will turn our seas into a graveyard for our marine resources,” he said. | |

| Sri Lanka stands firmly against trawlersThe Sri Lankan stance is clear: poachers and trawlers must honour the international agreement and stay out of Sri Lankan waters. However, some compromises have been suggested, given the recurring nature of the issue. The trawler fishermen of Palk Bay, from Nagapattinam to Rameswaram, are diverse, coming from various religious and social backgrounds with differing levels of connection to the sea. A common demand among them is to be granted permits to fish in Sri Lankan waters for two days a week, rather than the three days they currently attempt. Some even request “at least one day per week’’. Where fishing in Sri Lankan waters is not possible, many groups propose alternative livelihoods or compensation for giving up trawling. These ideas have frequently emerged during fishermen-to-fishermen dialogues organised by both civil society and the two national governments. Sri Lankan fishermen have been adamant about completely stopping trawling, except during a transition period. The recommendation for designated fishing days is a common solution proposed on multiple fronts, but there is a general agreement that trawling must be banned regardless. Neelima A, a researcher for the Centre for Public Policy Research, Kochi, suggests an ideal diplomatic solution should include both immediate and long-term strategies for sustainable practices and cooperation. She recommends that both countries ban harmful fishing methods, like bottom trawlers, and implement a rotational fishing system. This would allow Sri Lankan fishermen to fish in Palk Bay for three days, followed by three days for Indian fishermen, with one no-fishing day, ensuring “sustainability and equitable access to marine resources’’. Additionally, establishing a joint India-Sri Lanka maritime authority to monitor fishing activities and enforce regulations would be beneficial. Ms. Neelima also advocates for regular meetings and exchanges between fishing communities in Tamil Nadu and Sri Lanka to foster better understanding and cooperation. |

The best way to say that you found the home of your dreams is by finding it on Hitad.lk. We have listings for apartments for sale or rent in Sri Lanka, no matter what locale you're looking for! Whether you live in Colombo, Galle, Kandy, Matara, Jaffna and more - we've got them all!