In war and peace: A candid memoir

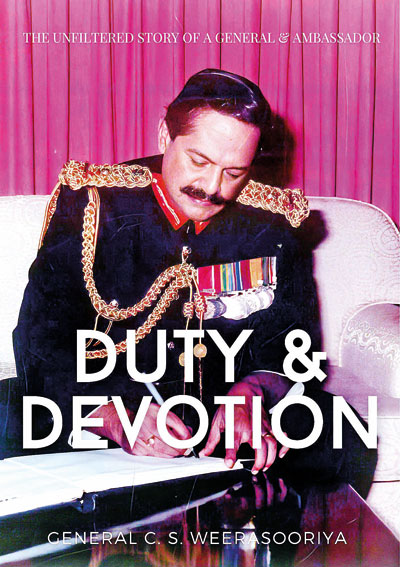

View(s):Former Army Commander General C.S. Weerasuriya’s memoir ‘Duty and Devotion – The unfiltered story of a General and Ambassador’ will be launched today at his alma mater S. Thomas College, Mount Lavinia. Here are edited extracts of two chapters ‘Elephant Pass’ and ‘The 9/11 Impact’ that cover very different and challenging periods of the General’s life. The book is a Vijitha Yapa publication.

Elephant Pass

The LTTE launched ‘Operation Unceasing Waves’ which, by its very name, indicated their intention to fight through until they regained control of Jaffna.

In early January 2000, the Brigade under the command of Brig Leonard Mark at Vettilekerni was threatened and was being gradually pushed back. 53 Division was deployed in the Soranpattu area to stem the LTTE, which was attempting to land north of Vettilakerni by sea, and cut off access to Elephant Pass.

More command problems arose. Brig Gamini Hettiarachchi, Commander 53 Division, had to be replaced due to medical reasons. Brig Sisira Wijesooriya, who replaced him, also did not last too long as he too fell sick, within a week of taking up the appointment. I then appointed Brig Seevali Wanigasekera in his place. Brig Wanigasekera performed extremely well and stabilised the area under his command.

Maj Gen Chula Seneviratne was the SF Commander in Palaly.

I sent the Chief of Staff, Maj Gen Balagalle, to Palaly to support him. From the reports I received, the LTTE was inching its way towards the water source at Eiyakachchi, north of Elephant Pass.

Brig Egodawela was the GOC at Elephant Pass, with Brig Percy Fernando as his Deputy. The troop strength was increased at Eiyakachchi, but by 15 April 2000, Vettilekerni had fallen. The water source at Eiyakachchi was under LTTE control.

The situation was critical.

I met the command element of the Elephant Pass troops, who briefed me, saying, “We have no recourse to water for our daily needs. We are not receiving any supplies by air or by sea.” It was difficult for the ground commanders who were unanimous in their request to withdraw from Elephant Pass.

“The decision to withdraw, if at all, has to come from the Security Council,” I said to Brig Egodawela. “Continue to hold Elephant Pass and regain control of the water source,” I said, promising them that I would not leave them to fight on their own if it came to the worst. By this time I gathered that several battalions of Elephant Pass troops had relocated on their own, to positions north of Eiyakachchi, where there was water.

I requested the Secretary Defence to summon the Security Council immediately so that I could brief them. President Kumaratunga was in London, and the Deputy Minister of Defence was in Nuwara Eliya.

On 20 April, we met with the Deputy Minister, and I briefed the Security Council on the critical situation at Elephant Pass.

The Security Council decided to pull back from Elephant Pass to Muhamalai, and thereafter, to strengthen the Chavakachcheri approach, thereby securing Jaffna.

I knew this decision would be interpreted poorly by the media and the public, but the fact of the matter was that we could do the same task we were doing at Elephant Pass from Muhamalai, where we had developed a defence line right up to the sea.

General Srilal Weerasooriya with Brig. Percy Fernando, Maj. Gen. Janaka Perera and others

Holding Elephant Pass, as I described earlier, was a prestige matter. We had fought tooth and nail to defend Elephant Pass in the past, but now the circumstances were different. Our troops at Elephant Pass were fighting with their backs to the wall. They had been unable to dislodge LTTE infiltrators who had come by sea and were dominating the area north of the main road leading to Elephant Pass. As much as I knew the media would go to town on this move, I also knew that the reality would remain unchanged – I was in no way ready to sacrifice the lives of the men at Elephant Pass on the basis of prestige or popular opinion.

On the morning of 21 April, the artillery guns, the 152 mm and 130 mm, were being moved out under the command of my former ADC, Capt Shiran Abeysekera, when they came under LTTE mortar and small arms fire. Shiran was injured, and during the evacuation, one 152 mm gun was left behind. It fell into the hands of the LTTE. Losing a piece of artillery was serious.

The planned withdrawal was on two axes: the main road, and the track along the Kilali Lagoon, which I used on 19 April. They were supported by Armour, Special Forces and Commandos. Much of the non-essentials, including ammunition, which could not be carried back, were destroyed at Elephant Pass to prevent them from falling into LTTE hands. This is the normal drill of a withdrawal.

Air Force helicopters and Artillery gave covering fire. The troops who took the main road had a fairly smooth run without much opposition, as the LTTE was concentrating on the second axis. By late evening the troops had moved out, but a large number of them died from dehydration.

The Deputy Divisional Commander, Brig Percy Fernando, succumbed to injuries caused by LTTE mortar shrapnel. According to reports Percy had the option of moving back in an Armoured Personnel Carrier but he, true to his character had said, “I will move on foot with my men.”

It was a tragic loss of a very good and efficient senior officer. Others who died, mainly of dehydration, were Col Bhatiya Jayatilleke, Col Neil Akmeemana, and Col Haris Hewaarachchi. The total number of casualties according to records at Army HQ were eight officers and 86 other rankers killed in action, and 14 officers and 227 other rankers missing in action.

Maj Gen Janaka Perera was appointed SF Commander Jaffna and Maj Gen Sarath Fonseka was appointed his Deputy. They had the task of holding the Jaffna peninsula.

The aftermath of the suicide bomb attack at PLC, Islamabad, March 2002

I returned to Colombo after debriefing Brig Egodawela and his command element. The Security Council met for an emergency meeting that night. There was total confusion. The Foreign Minister, Mr Kadirgamar, said “The country needs to be told of the situation and what happened at Elephant Pass.”

The question arose as to who would bell the cat. I said, “I will,” and volunteered to address a press briefing.

The Navy and Air Force Commanders joined me in appearing before the media, but they chose to remain silent throughout the conference. The journalists fired questions at us. “Why did you give up Elephant Pass?” I answered them.

As I anticipated, the media blew this out of proportion, even inflating the number of troops killed in action. They made it into the catastrophe of the century.

The 9/11 Impact

On 11 September 2001, Dilhani and I, together with my brother Richard (who was in Pakistan on holiday) were at the airport in Rawalpindi, awaiting the arrival of our friends, Druki Martenstyn and her mother Pam, from Sri Lanka, when we witnessed on TV the horrendous sight of the twin towers in New York being struck by two aircrafts.

America was shaken, and it was clear that the shockwaves would spread throughout the world in the years to come, with violence and counter-violence. I was keenly aware that Pakistan would be badly affected.

It was soon established that the Al Qaeda leader, Osama Bin Laden, had been given refuge in Afghanistan by the Taliban.

To cut a long story short, the Bush government prevailed upon Gen Musharraf to assist the US by requesting the Taliban to hand over Osama Bin Laden. The Pakistani Defence Minister made numerous visits to Kabul in this regard, but the Taliban would not budge from their stance that according to Islamic tradition, a person who seeks refuge has to be given hospitality and protection.

By 1997 the Taliban were in control of most of Afghanistan.Their government was recognised by Pakistan and the UAE.

After 9/11, the US had intelligence that Osama Bin Laden had been given refuge in Afghanistan. They demanded that he be handed over to the US, and issued several warnings to the Taliban to this effect, in the next few months. However, since the Taliban responded negatively to these warnings, the US and allied forces, called the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF), decided to launch an invasion of Afghanistan.

Meanwhile, in March 2001, the Taliban founder and leader Mullah Omar, ordered that the Buddha statues in the Bamiyan valley of Afghanistan be destroyed as they were ‘idols’ and therefore an abomination to Islam. The statues were 6th century monuments, carved out of the side of a mountain at an elevationof 8,200 ft.

The Bamiyan Buddha statues were a holy site for Buddhists on the ancient silk road. The international community condemned the impending destruction of the statues and Sri Lanka took the lead in the campaign to prevent the destruction from being carried out. It was for me to coordinate matters, being the Sri Lankan representative closest to the site.

I convened a meeting of the Ambassadors of Japan, Thailand, India, Nepal and Myanmar to discuss what should be done to prevail on the Taliban to desist from committing this dastardly act. The Prime Minister of Sri Lanka, Mr Ratnasiri Wickramanayake, flew to Islamabad prior to the destruction, to make representations to the Taliban, through the Taliban Ambassador there. I arranged an emergency meeting between the two at the Marriott Hotel. When the two officials met, the Taliban Ambassador informed our PM that the deed was already done. “The statues have been destroyed,” he said. This was before the discussion even commenced. What an anticlimax, after all the effort taken on our part. This act by the Taliban could only be described as criminal.

A group of freedom fighters, called the Northern Alliance (NA), comprising Uzbeks led by Gen Dohstum, and Tajiks led by Ahmed Shah Masood (known as the Lion of Panjshir, who was assassinated by the Taliban two days prior to the 9/11 attack), fought against the USSR, and resisted the Taliban. The NA supported the ISAF against the Taliban during the US-led invasion of Afghanistan. Due to the intransigence of the Taliban, the USA, supported by the ISAF, launched the invasion of Afghanistan in October 2001. The Taliban were, at this stage, in control of nearly 95% of Afghanistan. When fighting started in Afghanistan a large group of pro-Taliban tribal people from Pakistan, crossed over to Afghanistan to support the Taliban against the ISAF.

After the fall of Kabul and other major strongholds, the Taliban dispersed, and the Pakistani supporters withdrew to Pakistan.

The US invasion of Afghanistan caused retributive violence against Americans in Pakistan, including Christians in Pakistan (who were unfortunately seen as allies of America). During our time in Pakistan, my family and I worshipped at the Protestant International Church (PIC), which was located within the Diplomatic Enclave, next to the US Embassy in Islamabad. It was an interdenominational church which had a mix of Pakistani and foreign worshippers. In fact, we counted 14 nationalities, which included many diplomats, refugees, missionaries and NGO workers.

On 17 March 2002, our family was attending Sunday morning service at PIC. By this time many of the Western diplomats’ families had been recalled to their countries due to post-9/11 security measures. As such, there were only a few diplomats, NGO workers, Pakistani families and foreign missionaries in attendance that Sunday morning. Towards the end of the sermon, a man entered the church from a rear door and started hurling grenades into the sanctuary. The panic-stricken congregation rushed towards the exits. Dilhani and I were seated in the rear, close to the centre aisle. Amma was right at the back. Pearl and Rukshani were close to a window on the right side. Rushika was in the basement, teaching Sunday school. Knowing it was a terrorist attack, my wartime instincts took over. I shouted, “Get down.” The attacker walked to the centre of the church and detonated the bomb that was strapped to his chest.

It all happened in a matter of seconds, but the destruction of the interior of the church was total. Apart from the effects of the seven grenades that were thrown inside the church, the collateral damage caused by splinters of glass from shattered windows and the massive chandelier that was destroyed, was immense. A total of 5 people died and 45 were seriously injured. The suicide bomber’s head and limbs were scattered all over the church. Dilhani had shrapnel injuries on her legs and hands, while 84 year old Amma had shrapnel injuries on her ankles. Pearl and Rukshani who were seated by a window were miraculously spared of injuries.

Rushika’s story of what happened in the basement and how they were protected by an unknown person dressed in Afghan clothes is a miracle. We refer to the person as an Afghan angel as he was never seen before or after.

Rukshani, 17 years old at the time, chronicled her experience in detail, days after the attack. Her article is titled ‘Spared’ and was published in the Pentecostal Evangel in the US. It remains the first and only eyewitness account of what took place that horrific morning.

This attack, being the first suicide bomb attack in the history of Pakistan, sent shock waves through the city of Islamabad. Gen Musharraf was particularly upset by it. He invited us to his home and requested us to give him all the details we could, of what took place. At the same time, the FBI launched its own inquiry, as two of the persons who died that morning were US citizens – one, a child of just 17.

‘Duty and Devotion- The unfiltered story of a General and Ambassador’ will be available at Vijitha Yapa bookshops from tomorrow. It is priced at Rs. 3,500

| Batik shirt to the rescue The LTTE began its offensive stance in a more deliberate manner, after its success in Vavuniya. On the afternoon of 10 March 2000, an LTTE group of about 10, laid an ambush on Parliament Road in Rajagiriya. The MOD bills were to be taken up in Parliament that afternoon, and so the three Service Commanders and the Deputy Minister of Defence were in Parliament. While the session was in progress, we were informed that a bomb had been detonated in Rajagiriya, impacting a number of civilian passenger-vehicles. It transpired that the LTTE group, disguised as cricketers, carrying cricket bags, occupied an abandoned house by the main road. They had set up a series of claymore mines along the road, with the intention of ambushing the military high-ups on their way back. A police constable on picquet duty on the main road had, however, gone to the abandoned house in search of a place to answer a call of nature. When he stumbled on the heavily armed group in the house, he raised the alarm. The LTTE group, realising that their game was up, shot him and detonated the claymores that were placed at random along the vehicle-congested road. Several vehicles were damaged, 36 civilians were killed, and about as many were injured. The LTTE group, having failed at their mission, began to run along the railway line towards Wanathamulla, shooting at random. We were advised to stay in the Parliament complex until a helicopter arrived to lift us to Colombo. However, I could not wait for the helicopter, so I contacted the Colombo Commander Maj Gen Marambe. “Track the movements of the LTTE group,” I said. “And call for the Commandos.” Thereafter, I wore a batik shirt over my uniform, got onto the pillion of one of my escort riders, used the back road through Thalawathugoda, and reached my official residence on Bauddaloka Mawatha within 15 minutes. Dilhani and the girls were seated on the front steps, worrying and praying. I could see their shock and surprise when they realised the smiling man in the batik shirt who was just let into the premises, on the back of a motorbike, was me. When Athulathmudali became Athul Mudal Ali There were 90 diplomatic missions in Islamabad, and so there was a busy diplomatic social calendar with very few days off. One had to be vigilant to keep up with it all on a daily basis. During a function one evening an eminent Pakistani gentleman said he had been closely associated with the late Lalith Athulathmudali at Oxford. He lamented the fact that a Muslim holding as high a position as Minister of Internal Security in Sri Lanka had been assassinated. I agreed that Mr Athulathmudali’s assassination was a great loss, but I also said, “Mr Athulathmudali was a Sinhalese Buddhist, not a Muslim.” “Oh, I always thought he was a Muslim because of his name,” the man said. This was even more curious than his previous statement. “What do you mean?” I asked. To which, he responded, “Athul Mudal Ali is a Muslim name!” I did my best to keep a straight face. Shakespeare said “What’s in a name?” but at times, there is so much!

| |

Searching for an ideal partner? Find your soul mate on Hitad.lk, Sri Lanka's favourite marriage proposals page. With Hitad.lk matrimonial advertisements you have access to thousands of ads from potential suitors who are looking for someone just like you.