Lanka’s earliest links to Linnaeus

View(s):By Ismeth Raheem

It is a widespread perception among the general public and a view prevalent among academic circles that Sri Lanka’s contribution to the development of science is trifling and insignificant.

This approach overlooks the contribution that has been made over centuries in the fields of industry (manufacture of steel), hydraulic engineering and surveying (irrigation – construction of large scale reservoirs and channels) and medicine (variolation and immunization procedures).

Significantly it is in the natural sciences we seemed to have made some impact, particularly in the interest shown in our endemic flora by a writer (supposedly A.M. Ferguson), a century and quarter ago;

“The Sinhalese, as a race, have been credited with being “natural botanists” and have supposed to have possessed in pre-European times, a system of classification of their plants, as so many of their vernacular names would indeed, seem to indicate. Those of us who have any acquaintance of plants in other countries cannot but be struck with the comparative intimate knowledge which the Sinhalese have of native plants and their uses, as with the wealth of vernacular plant names which unlike so-called English have the merit of being usually descriptive.”

Often in such fields, particularly natural history, researchers have belatedly discovered what practical persons working in the natural world have been aware of for centuries and to some extent have understood.

Sir Alexander Johnston (1775-1849), Privy Councillor, FRS, our third Chief Justice was curious of all aspects of human activity and of every facet of the colony whether judicial, political, economic, social or cultural. Johnston attempted to improve the newly colonized country’s interest in science. His suggestion to establish a zoological society was ignored by the higher officials in London, but he was one of those liberal minded persons like Sir Joseph Banks who encouraged the then British government here to establish a botanical garden as early as in 1811.

He did not ignore the vernacular languages and their historical roots either. Over time, Johnston presented copies of the original text of the chronicles – the Mahavamsa, Rajaratnakara and Rajavaliya to the pundits and scholars in this country. As Chief Justice, by 1805 he introduced a range of administrative reforms and was a fierce advocate of the rights of the native people.

On his annual circuit to the Northern provinces in 1806, he documented several interesting unique features of the customs and rituals in Jaffna of the various communities. One aspect that intrigued him most was botanical observations of the inhabitants.

Possessing an enquiring mind, he consulted a wide range of personalities and among them met a group of Brahmin scholar priests, on what was then common knowledge among them, discussing several important attributes of their life and rituals.

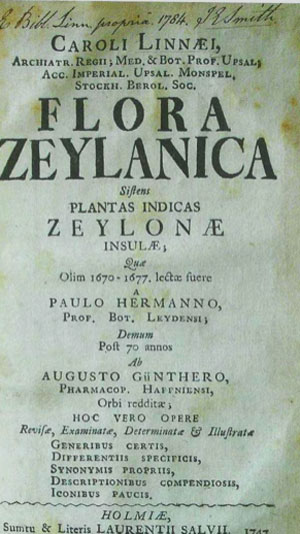

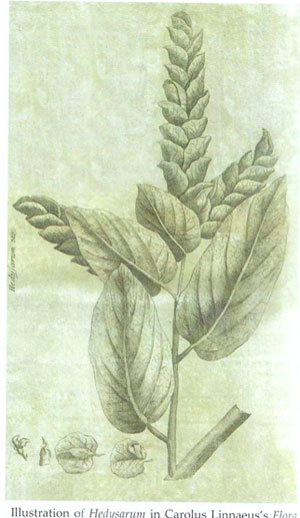

Title page of Linnaeus’ own copy of Flora Zeylanica and right, an illustration of Hedysarum in the book (from Rohan Pethiyagoda’s Green Gold)

Johnston made the following intriguing comments of which he proposed research and study;

“They are enquiring into the natural history of the island, its zoology and botany, into the character and habits of its elephants and the practicability of adopting them into particular description of labour; into the growth and culture of cinnamon, of its Chaya root (the Oldenlandia umbellate of Linnaeus) and of its several varieties of the palms; of the Tallipot (the Corypha umbraculifera) and the Jaggery (Caryota urens) in the interior, of the coconut (the Cocos nucifera) in the south and of the Palmyra (Borassus flabellifer) in the northern province;

Into the local limits within which each of these are brought to perfection; into the several uses and manufactures to which they are applied; Into the moral and political effects which they have produced upon the situation, and the habits of all they have produced upon the situation and habit of all the people who are employed in their cultivation, and in the manufacture of their produce.

Into the practicability forming a botanical map of the whole island. Into the knowledge, which the natives of Jaffna have possessed from the earliest times, of the male and female of the palm called the Palmyra palm, or borassus flabellformis.

Into the practical use which they have made of that knowledge. Into the manner in which it was first communicated by them to the Dutch botanist Herman, while he resided in Ceylon from 1670 to 1677; and into that which it was fifty years after his death, communicated by August Gunter, an apothecary at Copenhagen to Linnaeus, who on receiving Herman’s papers from him, discovered the information which ultimately led that great naturalist to the classification of all vegetable production according to the sexual system. (highlighted by author)

Having explained to the Society the different points to which the researchers of the Committee have been directed during the last twelve months I shall take the liberty to call to their attention to some event which must facilitate the future proceedings of the Society, and extend the influence of science and literature, over the Hindus and Mohammedan population of Asia.

The Swedish-born Carl von Linnaeus (1707-1778) was the founder of modern taxonomy and formulated ideas on a much earlier and simpler version of a similar nomenclature based at a genus level of an Aristotelian concept.

In his essay Alexander Johnston was imputing that the basis of Linnaean concept of classification based on male and female features of a flower was a notion that was known in Sri Lanka for centuries. But no doubt we are well aware that it was Linnaeus who codified and structured the whole concept that led to formulating the epoch-making concept of Binomial classification. Also, in no way is Johnston downplaying Linnaeus’ role in advancing his far-reaching work

Linnaeus, the founder of modern taxonomy, based his basic ideas on a much earlier and simpler version of a similar nomenclature based at a genus level of an Aristotelian concept.

For almost a decade Linnaeus pursued his passionate interest in conducting the research and study of Sri Lanka’s flora and most importantly Hermann’s herbarium which came into his hands. Between 1672-1677, Paul Hermann (1646-1695), physician and botanist while serving as the Chief Doctor of the Dutch Hospital in Colombo, conducted a thorough field survey of the flora in the neighbourhood of Colombo. He collected over 1000 species. These were compiled into four volumes and some of the important endemic species of plants were illustrated. While employed in such botanical activity, Hermann also attempted to master the Sinhalese language, and took care to note the Sinhalese names of each plant and their applications particularly those used for medicinal functions with help from his native assistants many of whom were Ayurvedic physicians.

Hermann during his field survey and collection was assisted by native ayurvedic physicians. Later European botanists of the 18th century, reformulated and published these botanical observations in their scientific work. This was exactly what Johnston hinted at in his comments.

The rediscovery of Hermann’s herbarium which was compiled between 1672-1679, in several volumes including hundreds of illustrations, was an opportunity Linnaeus would have not ignored. By the 1730s the study of the tropical flora of this country was an idea fundamental to Linnaeus.

Of his herbarium collection, 130 species are still listed in Sinhalese medical literature. After his return to Leiden, Holland, in 1679 and soon after his death in January 1695, Hermann’s herbarium (Musauem Zeylanicum) was thought to be lost or misplaced. Fortunately, the work was rediscovered by the Danish Apothecary-Royal, August Gunther and handed over to Linnaeus in 1744.

On receiving Hermann’s herbarium Linnaeus set to work and within three years published the Flora Zeylanica in 1747, at Upsala, Sweden. This publication was the first descriptive flora on a scientific basis of any Asian country. Subsequently he enlarged the scope of his research and after establishing the binomial taxonomic system, globally, still in use, he published the Species Plantarum in 1753, in which he included most of the previously listed Sri Lankan plant names.

Most intriguingly Linnaeus adopted the original Sinhalese names as mentioned in Hermann’s herbarium but Latinized and published these with the new scientific names in his own work. For almost 30 species Linnaeus used generic plant names based on the Sinhalese names such as Doona- dun (Sinhalese)-smoke; Elephant topus- et adi (Sinhalese) Elephant foot;Embelia- ambul (Sinhalese), sour: Ixora- Iswara (Sinhalese) Hindu god; Naravelia-nahara- (Sinhalese) nerve: Nelumbium. Nelum (Sinhalese), Lotus; Wissaudula- wisa (Sinhalese) poison; There were as many as 30 or more names Linnaeus included in his work.

No doubt, more research is needed to establish the “smoking gun” to arrive at some positive conclusion that such concepts were borrowed originally from Eastern sources.

A similar striking example of an earlier date of discovery could be cited in the field of medicine.

It is now an established fact that the medical procedure known as variolation and also immunization was known in Asia for centuries before the discovery attributed to the English doctor, Edward Jenner from his findings in 1796. It was found that this technique could reduce the effect of serious infection of the body. This medical fact was known to Sinhalese Ayurveda practitioners for centuries.

Gideon Loten (1710-1789), Dutch Governor and Head of the Dutch East India Company’s territories in Sri Lanka between 1752-1757, made this observation during an epidemic of smallpox raging in maritime provinces in his memoirs to his successor Governor Jan Schreuder on February 28,1757.

“Consequently, it would be very desirable for this country if the people here would adapt the same treatment as that practiced by the natives of Java, Macassar and elsewhere, namely of washing the sick; for one hardly ever hears the case of failure among the natives here in Ceylon, while the Sinhalese who are stricken with the disease rarely ever escape;

And not withstanding our frequent efforts at persuasion and the successful examples before their very eyes when the disease was raging severely, they did not follow them, giving as their excuse the reason, that the constitution of their bodies was different; and much less less would they be willing to submit to the use of the very salutary and universal remedy, which having originally come from Asia and passed into several counties into Europe and even America, has had such happy and certain results in various climates temperate as well as tropical but this only in passing.” (Inoculation refered to in passing).

The unfortunate situation that prevailed in countries in the East such as in Sri Lanka and elsewhere in Asia, is that the practitioners did not systematically record and publish their observations, moreover, due to a lack of such institutions or organizations for example like the Royal Society in England (est. 1660) which encouraged the public to experiment and publish their findings.

Searching for an ideal partner? Find your soul mate on Hitad.lk, Sri Lanka's favourite marriage proposals page. With Hitad.lk matrimonial advertisements you have access to thousands of ads from potential suitors who are looking for someone just like you.