Born in Travancore, worked in Ceylon and buried in Borella

View(s):Rahul Jacob on a mission to find the grave of his great-grandfather Dr. K.K. Jacob from India, who had headed the Infectious Disease Hospital in Colombo between 1916-’34

The Borella cemetery in Colombo, Sri Lanka, could double as a sculpture garden. Angels tower over gravestones with wings so delicately carved that they appear about to take flight. The funeral parlour for Buddhists is a minimalist marvel in pristine white. The Christian chapel with its vaulted wood and tiled ceiling and stained-glass windows is similarly uplifting. Gardeners and cleaners roam the place sweeping away fallen leaves as if honouring a sacred duty.

Dr J.M.J. Supramanian: The doctor from Jaffna who made his mark in Singapore

On a Saturday in May, I visited the cemetery not to take in its beauty, but on a mission. Just weeks earlier, I had learnt that my great-grandfather was buried there. I knew he had died in 1933 or 1934, but that was all the information I had and thus went with little hope of finding his grave. The person in charge of the office for the Christian cemetery didn’t seem the least bit flustered by this paucity of information. He explained that many diaspora, especially Burgher families living overseas, routinely came to the office seeking to find ancestors’ graves.

And, indeed there was my grandfather’s name, with the plot’s location: Dr K.K. Jacob, 5A 024A. The lined notebook where the records of 1934 were kept had been elegantly rewritten, the roll-call of burials looked as if an entry in a handwriting competition.

The person in charge then consulted an old record of the plots from that time. Scarcely 150m away from the office, we were standing in front of the grave. Ninety years almost to the month after he had died, the lettering on the gravestone was still easy to read: “In Loving Memory of Kaithail Koshi Jacob… Died 8th April 1934.”

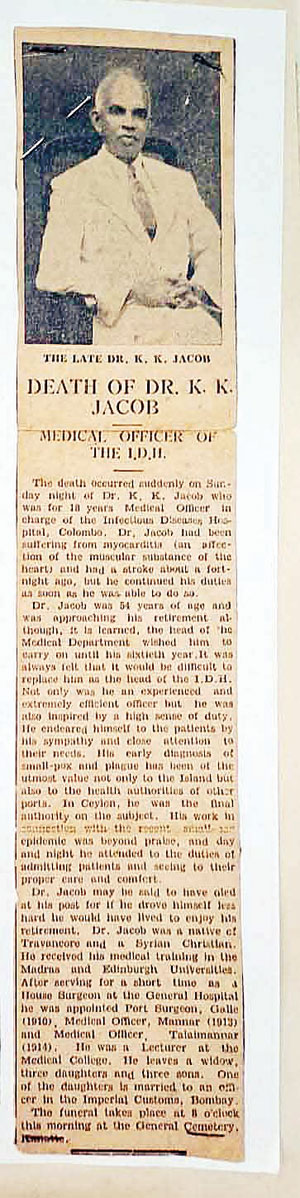

Weeks earlier, when I had learnt from a cousin in Chennai that my paternal great-grandfather was buried in Colombo, I had joked in an email to a Sri Lankan friend that I should have visa-free access to the country since my great-grandfather’s work as a doctor there had likely helped his ancestors recover from dysentery. In fact, as often happens, the real story was much richer. Dr. K.K. Jacob had headed the Infectious Disease Hospital in Colombo approximately between 1916-’34. His obituary published in a local newspaper applauded “his early diagnosis of smallpox and the plague as (having been) of the utmost value not only to the island but also to the health authorities of other ports. His work in connection with the recent small-pox epidemic was beyond praise.”

Paper cutting of the obituary

In a world of Google, Netflix and outsourcing, most of us likely assess our times as the high watermark of globalisation. But, the arc of K.K. Jacob’s life was a reminder that the late 19th century and early 20th century was also a period of unfettered globalisation and cosmopolitanism, in large part because it was a heyday of British imperialism. Before his medical career of almost a quarter of a century in what was then Ceylon, K.K. Jacob had grown up in Travancore and studied medicine in Madras and Edinburgh. He was not by any means unique in making a career in another country. Many others were pulled along by the engine that was British imperialism and much more open borders, including the Chettiars to South-East Asia and Gujaratis and Sindhis to Africa.

Although colonialism is rightly critiqued for its dense web of social and economic exploitation, it also made possible relatively free movement of businesspeople, professionals and civil servants across continents.

In late June while I was in Colombo, I learned of a remarkable story of a Jaffna Tamil doctor, James Mark Jeyasebasingam Supramanian, who imprinted himself not only on colonial Singapore’s history but also in the annals of medicine by devising efficient, cost-effective treatments for tuberculosis in Singapore. The method he refined by using Rifampicin and pyrazinamide for treating the disease was an adaptation of the treatment devised at the Edinburgh Medical School. It was adopted by the World Health Organisation in the 1960s.

Writing The Economic Consequences of Peace (1919), the economist John Maynard Keynes, had issued a kind of nostalgic benediction on the globalisation the world—or rather his world—had enjoyed until the outbreak of World War I in 1914: “The inhabitant of London could order by telephone, sipping his morning tea in bed, the various products of the whole earth, in such quantity as he might see fit.” Reading this today is discomfiting because we know that hundreds of thousands of indentured labourers travelling from India and Africa to plantations overseas made the globalised world Keynes idolised in that passage possible. In Sri Lanka, the sad plight of the Malaiyaga Tamils is a reminder that ‘Ceylon tea’ also has a grim past and present. But, Keynes was making a fair point when he said that the Industrial Revolution and this opening up of the world also made advancement possible into the middle and upper classes “for any man of capacity or character at all exceeding the average, for whom life (then) offered conveniences, comforts, and amenities beyond the compass of the richest and most powerful monarchs of other ages.”

The extraordinary career trajectories of Dr. K.K. Jacob and Dr. J.M.J. Supramanian, who presciently called for a ban on smoking in public spaces at the World Tuberculosis conference in New York in 1969, are emblematic. While only in his thirties, Dr JMJ advised the British governor of Singapore to introduce compulsory BCG inoculation for all children after becoming one of the first local heads of department in 1958 while Singapore was still a colony.

It is hard to guess how K.K. Jacob’s career would have played out if he had stayed in his native Travancore, but his career as an expatriate Indian in government administration and hospitals in Sri Lanka could not occur today. After World War II, and especially in the last few decades, visas and work permits have tightened up. My great-grandfather’s obituary mentions that the authorities wanted him to delay his retirement till he was 60. He died a month or so short of turning 54. “It was always felt that it would be difficult to replace him as the head of the IDH,” the writer of the obituary observed. “In Ceylon, he was the final authority on the subject (of smallpox and the plague).”

My great-grandfather quite literally worked himself to death. Just a fortnight before his death, he had had a stroke. He was suffering from myocarditis, an inflammation of heart tissue. In an era before antibiotics, the condition was incurable. Before he had fully recovered from his stroke, he was back at work. As the obituary noted, “Dr. Jacob may be said to have died at his post for if he drove himself less hard, he would have lived to enjoy his retirement.”

All intact and easily accesible at the cemetery office: An old record of the gravestone plot

Last year, while on a trip to Colombo, I needed to take the third dose of a rabies vaccine after having been bitten by a dog in Bengaluru. On a weekend morning, I went to the National Hospital of Sri Lanka. I trudged up the road expecting the long waiting periods and organised chaos of an Indian government facility. Instead, I was administered the injection in the well-laid out rabies treatment unit within minutes of arriving. As Swati Narayan observes in her book Unequal: Why India Lags Behind its Neighbours, Sri Lanka’s public health system is well ahead of its South Asian neighbours.

Harder to comprehend for me is how Colombo has long been a second home after repeated visits since 2002. Like an archaeological excavation, the coincidences lie layer upon layer. Writing my will a few months before I discovered his grave, I had requested that a small portion of my ashes be dropped at the foot of my parents’ grave in Bengaluru and deleted an impractical plea that a handful be dropped somewhere in the Borella cemetery because I had become so enamoured with its tranquillity and beauty, opting instead for the sea at Bentota. The Colombo gym I regularly exercise at begins its warm-up jogs a little past dawn along the perimeter of the cemetery. On more than a few occasions earlier this year, I had thus been a couple of hundred metres from my great-grandfather’s grave without knowing it.

I have often quoted the late writer Gita Mehta’s witty remark that “karma is not everything it is cracked up to be.” Now, I am not so sure. Standing before my great-grandfather’s grave in late May and listening to the story of Dr. J.M.J. Supramanian from his son who I met by coincidence at the end of June, I am conscious of a curious paradox. I am a journalist at a loss for words, an agnostic trying to make sense of the long tail of fate and history.

90 years almost to the month after Dr. K.K. Jacob had died, the lettering on the gravestone was still easy to read

(Rahul Jacob worked as a foreign correspondent and a travel editor for the Financial Times, London)

Searching for an ideal partner? Find your soul mate on Hitad.lk, Sri Lanka's favourite marriage proposals page. With Hitad.lk matrimonial advertisements you have access to thousands of ads from potential suitors who are looking for someone just like you.