News

Sri Lanka’s first Albatross sighting thrills birdwatchers

View(s):

Lahiru: Daily observes seabirds in Mannar

By Malaka Rodrigo

Lahiru Walpita, an avid birdwatcher based in Mannar, spends his days combing the beaches in search of seabirds. On the morning of July 22, at around 5.45 a.m., something caught his attention; a large seabird appeared on the horizon. The bird was following a boat.

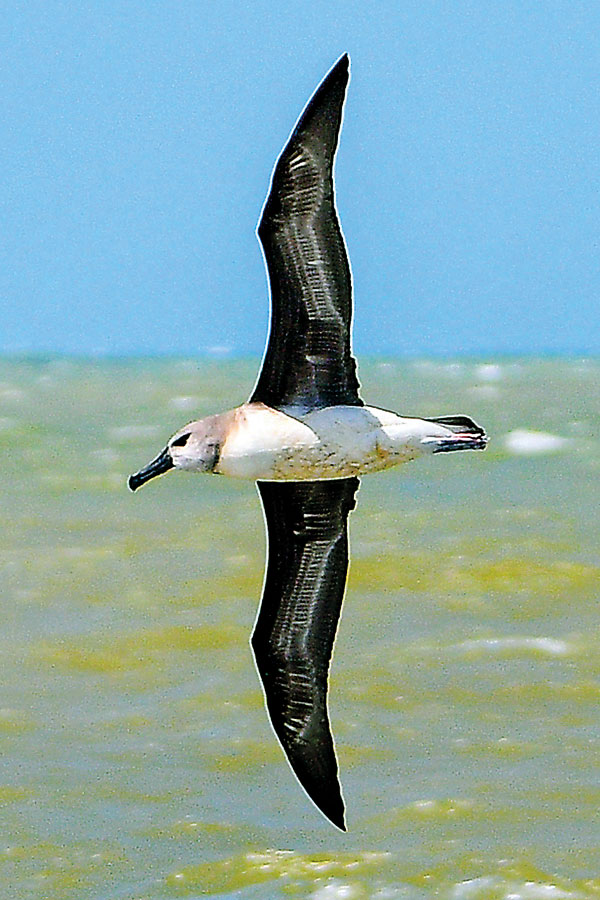

Eagerly peering through his spotting scope, Mr. Walpita hurriedly noted the bird’s features and was thrilled to identify the unmistakable beak pattern of an albatross. Later, around 10 a.m., he spotted the bird again. This time, he managed to take some clear photographs.

There are several species of albatross, so Mr. Walpita shared the photos with more experienced birders. With their help, the bird was identified as a grey-headed albatross (Thalassarche chrysostoma), based on its distinctive features—primarily a white body and a slate-grey head and neck.

“This could be one of the biggest finds of the century for Sri Lankan birds,” says Prof. Sampath Senevirathne, an ornithologist at the University of Colombo. There are about 30 species of albatross worldwide, most of which inhabit the Antarctic and other southern polar regions, except for three species. This is the first recorded observation of a living albatross in the Northern Indian Ocean, says Prof. Senevirathne, highlighting the significance of the sighting.

The grey-headed albatross photographed by Lahiru Walpita off Mannar.

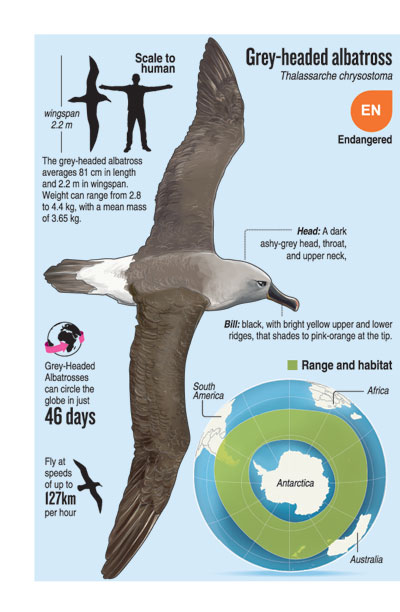

Albatrosses are large seabirds that travel long distances. The grey-headed albatross, for example, has a wingspan of 2.2 metres (7.2 feet), making it a gigantic bird when it spreads its wings. The large wingspan of albatrosses, including the grey-headed albatross, is a remarkable adaptation that enables these birds to thrive in their oceanic environment, says Prof. Senevirathne. Some species, like the wandering albatross, can have wingspans of up to 3.5 metres (11.5 feet). Their wings are long and narrow, and this shape is ideal for gliding and soaring, as it reduces drag and allows for sustained flight. Their large wings distribute their body weight, making it easier to glide efficiently over the ocean, explains Prof. Senevirathne.

The grey-headed albatross primarily flies around the South Polar region and only comes to land to raise its young. The birds lay their eggs on islands, and the parents take turns caring for the young. While one stays with the chick, the other goes to sea to forage for food, a process that can take a week or two and involves travelling across the southern ocean. Upon returning, they feed the chick a nutrient-rich substance, and then the other parent leaves to forage.

Prof. Senevirathne explained to the Sunday Times that this feeding cycle requires incredible stamina and endurance.

Albatrosses have a long lifespan, with some species reaching the age of 70 years. They require predator-free islands to lay their eggs, as they nest on the ground where small mammals like mice or snakes can threaten entire colonies. Albatrosses also have a tendency to follow fishing boats in search of an easy meal, but they often become entangled in long-line fishing hooks when attempting to take bait, resulting in drowning.

Additionally, albatrosses often mistake plastic debris for food, leading to injury, starvation, and death. Overfishing reduces the populations of squid and fish that albatrosses rely on, further threatening their survival. These factors collectively make the species vulnerable, as increased adult mortality can cause a drastic decline in the population, says Prof. Senevirathne.

The grey-headed albatross is categorised as endangered, with the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) estimating their global population to be about 250,000 to 300,000, with a declining trend. Some species of albatross have nearly become extinct, with only a few dozen surviving, Prof. Senevirathne said, adding however that international conservation organisations are taking action based on scientific methodologies to minimise the threats faced by albatrosses. This has led to some conservation successes, with populations of most being stable, he said.

Climate change is also expected to impact albatross species, as changes in ocean temperatures and currents affect the availability of prey such as squid and fish. Rising sea levels and increased frequency of storms can damage breeding sites on remote islands, which can be particularly harmful for species like the albatross that have fewer broods.

Prof. Senevirathne, who conducts research in Mannar, praises Mr. Walpita’s dedication to seabird observation, noting that seabirds are one of the most challenging groups of birds to study. He said Mr. Walpita has provided a number of dead seabird specimens he found on the Mannar coast, some of which are first-time records.

Meanwhile, Mr. Walpita told the Sunday Times that he began birdwatching seriously in 2020 and focused more on studying seabirds in 2021, inspired by a few other birdwatchers who started engaging in seabird observations. Mr. Walpita begins his birding sessions daily at 5.30 a.m., walking a 5 km stretch along the beach in search of seabirds. He also rescues seabirds that have difficulty flying and collects carcasses to send to the University of Colombo’s specimen collection.

The best way to say that you found the home of your dreams is by finding it on Hitad.lk. We have listings for apartments for sale or rent in Sri Lanka, no matter what locale you're looking for! Whether you live in Colombo, Galle, Kandy, Matara, Jaffna and more - we've got them all!