Why we need leopards in Sri Lanka

To me, the leopard, with its dappled coat, perfectly crafted by nature for camouflage, is the epitome of strength and grace in movement. To me, the leopard is an animal on which I focused for many years of my student life and about whose well-being, my passion continues to this day.

However, to a labourer in a tea estate, it is a fearful predator which can attack him/her. To a politician, the leopard, just like most other elements of the natural world, does not fall within the purview of obtaining votes. To those promoting nature tourism in Sri Lanka, the leopard is one of the big four attractions that can generate income. To the amateur wildlife photographer, the leopard is a must-have shot when visiting Yala or Wilpattu.

The Sri Lankan leopard (Panthera pardus kotiya). Pic courtesy WNPS

Each person’s perspective of the leopard is different. But the fact is that leopards are important to all of us.

This is because they are apex predators. Many articles about Sri Lankan leopards often state ‘The Sri Lankan leopard is an apex predator’. They proceed to explain that as apex predators, leopards in Sri Lanka are ecologically important. But why are they ecologically important? And how are they important to all of us?

An apex predator is at the very top of a food web, with no natural predators of its own. Apex predators include tigers in several Asian countries, lions in sub-Saharan Africa, grey wolves in Yellowstone National Park, USA, jaguars in South America, killer whales (orcas) in many oceans, and our very own leopard in Sri Lanka in terrestrial ecosystems. Unlike on the African continent and in mainland Asia, where leopards are subordinate to lions and tigers, the Javan and Sri Lankan leopards are the dominant, apex predators.

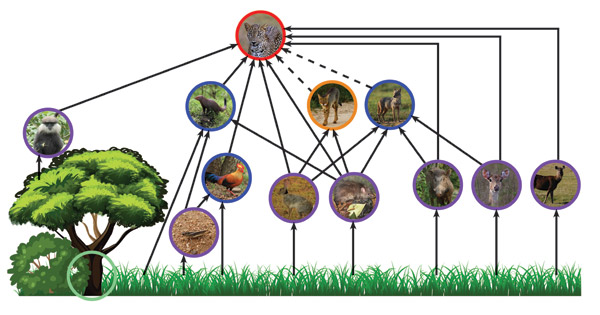

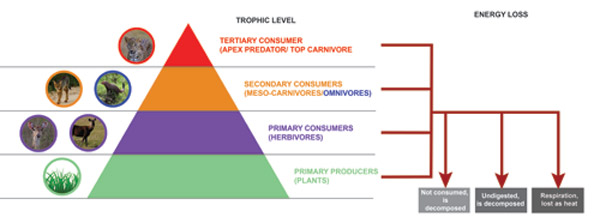

A food web is a hierarchy of complex interconnections among species in an ecosystem, based on what each species eats. (See Figure 1.) So, there are several trophic (meaning feeding) levels in a food chain/food web, and this is the position or rank of an organism in a food chain/food web. The basic trophic level comprises organisms that make their own food – primary producers. In terrestrial food webs, these are plants. Herbivores (such as spotted deer, sambur and purple-faced leaf monkeys), which consume these plants make up the next trophic level and are primary consumers. Medium-sized carnivores (such as jungle cats) and omnivores (such as jackals and mongooses), which feed on primary consumers and therefore, form the next level up in the food web, are known as secondary consumers. The final, the top tier has leopards, which are tertiary consumers. Therefore, in feeding rank, the leopard is the highest, apex predator.

Through each trophic level, energy (which an organism needs to live) is transferred from a lower trophic level to the next. This is shown in Figure 1 by the direction the arrows point.

But at each of these levels, energy is lost (as much as 80-90%) as heat through respiration. Also, there is a part of food that is not consumed or not digested (such as bones). Therefore, there are fewer and fewer organisms at each trophic level, which, pictorially, would look like a pyramid – a trophic pyramid (Figure 2). At the top of this pyramid, there are very few leopards, compared to plants and herbivores.

Although so few compared to other species, these apex predators play a disproportionately important role in the ecosystems in which they live.

Extensive decades-long studies of what happened when another apex predator was extirpated, at another time, in another part of the world, give us a clear snapshot of what is in store for us if the leopard becomes extinct in Sri Lanka.

Figure 1 : Simplified food web with the leopard as the apex predator in, say, Yala National Park. Green outlined circle=primary producer; purple=primary consumers; blue and orange=secondary consumers (orange=carnivores; blue=omnivores); red=tertiary consumers. The dotted lines are inferred from literature from other parts of the world but not recorded in Sri Lanka.

At the turn of the 20th century, a programme was begun by the US government to eradicate grey wolves in the western USA to protect livestock from predation. By mid-century, grey wolves had been exterminated in most of the US states and also in Yellowstone National Park in the western USA. For 70 years, there was no apex predator in Yellowstone. Without an apex predator to keep their populations in check, deer and elk populations exploded, eating up the barks of trees such as willow, aspen and cottonwood. This resulted in greatly reduced growth and eventually the loss of entire stands of trees. With fewer willow trees along the banks of rivers, these banks began to erode. Without willow trees to feed on and to build their dams, all but one colony of beavers disappeared and with them, many other aquatic species. With the de-barking of trees, pathogens had a field day, killing off more trees. With fewer trees, there were fewer songbirds. The food web was disrupted and the entire Yellowstone ecosystem collapsed, with a change that occurred at the top of the food web, spilling down in a domino effect of unexpected changes, technically called a trophic cascade.

Then three decades later, as it became apparent to biologists that somehow wolves were important to this ecosystem, 14 wolves were re-introduced to Yellowstone National Park. The changes were immediate, as wolves started to prey on elk. But their presence also triggered a behavioural response in these hoofed mammals – who began avoiding valleys and gorges where the predators could hunt them easily. Then, as these avoided areas started regenerating, birds and beavers came back. Even bears returned because now, there were berries to eat. With the growth of trees, riverbanks stabilised, and with it the course of the river. Beavers, back once more, built their dams and created microhabitats for species such as otters, ducks and fish. The ecosystem was transformed by the reintroduction of its apex predators.

Photo credits: Riaz Cader, Sampath de Alwis Goonatilake, Chitral Jayatilake, Niroshan Mirando, Luxmananan Nadaraja, Indika Nettigama, Nadeera Weerasinghe)

Another example in the state of Bolivar, in Venezuela, tells of a complex of hydroelectric dams which was built across the Caroní River in 1986, flooding the area and creating the enormous Lake Guri. With the flooding, hilltops in this area were transformed into islands, well isolated from each other, as well as the mainland. This set the stage for a natural experiment. Before the construction of this dam, this area contained apex predators, such as jaguars and harpy eagles, and herbivores such as howler monkeys, iguanas and leaf-cutting ants. With the flooding, small- and medium-sized islands could not sustain their apex predators (the habitat was, simply, not large enough). Without predators, the prey populations exploded: with iguanas to 10 times, howler monkeys to 50 times and leaf-cutter ants to 100 times the densities in the mainland. On each island, the habitat has been transformed by its herbivores. Where once there were many herbaceous plants on one island, there is now bare land covered with capybara dung. Where once there were birds on another, omnivorous capuchin monkeys have eaten all but 10% of the bird population. Where once there was a diverse landscape in yet another, only plants which agoutis like to eat are thriving, because agoutis bury only these seeds.

This is why leopards, like any other apex predator, are ecologically important in Sri Lanka. Without them, sambur, deer and wild boar populations will increase uncontrollably and eat up all the natural vegetation, in addition to our crops. (Wild boar are considered pests in agriculture.) Leopards exert a huge influence on the ecosystems in which they are. Natural ecosystems are not just important for their stunning vistas and incredible species, but they are also critical for our – human well-being. The smooth functioning of ecosystems yields benefits to us humans – the very oxygen that we breathe; the water we drink; the food that we eat; the many medicines that we take and the wood and fuelwood that we use. Species in ecosystems degrade our waste (but not plastic), regulate our climate, protect us from floods and famines, purify our waters and detoxify our soils. Ecosystems sustain our lives.

So, ultimately, conserving leopards in Sri Lanka, because of their position in the ecosystem, benefits all of us who live in Sri Lanka no matter what perspective we have about its conservation.

Unfortunately, though, as Arian D. Wallach and his co-workers write, we humans have turned ourselves ‘into the fiercest and most dangerous predator on the planet. . . and are arguably apex predators in our own right’. We are, in fact, super apex predators, triggering not just the collapse of a single ecosystem but a sixth mass extinction and the collapse of a planet.

| Sri Lanka Leopard Day | |

| On August 1, Sri Lanka celebrates Sri Lankan Leopard Day based on a proposal put forward by the Wildlife and Nature Preservation Society of Sri Lanka (WNPS), Sri Lanka’s oldest (and the world’s third oldest) nature protection society. The Multi-Regional Monitoring System for the Sri Lankan Leopard project established in early 2022 through the joint efforts of LOLC Holdings PLC and the WNPS is designed to monitor and protect the nation’s apex predator against both longstanding and emerging threats. While many of the leopards within natural reserves and sanctuaries are identified and accounted for, there remains a pressing need to understand the distribution and behaviour of this species outside the protected zones. The Multi-Regional Monitoring System will rely on a collaborative research-based model to gain a deeper understanding of the core issues as more reports of leopard deaths and close interactions between humans and leopards come in. The hope is that this can improve understanding of the complex dynamics that exist between humans and leopards across the island, and enable solutions to mitigate the challenges faced by both parties on a daily basis.

|

Searching for an ideal partner? Find your soul mate on Hitad.lk, Sri Lanka's favourite marriage proposals page. With Hitad.lk matrimonial advertisements you have access to thousands of ads from potential suitors who are looking for someone just like you.