“Primary balance hypothesis”

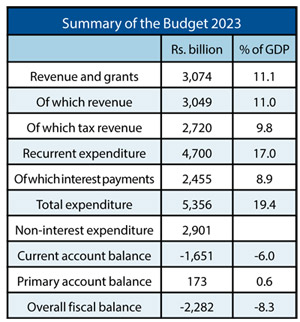

View(s):In all previous occasions – 1955, 1992 and 2018 – interestingly, voters defeated that government at the next elections. Last year, 2023 too, the government has been able to achieve a primary account surplus of Rs. 173 billion (0.6 per cent of GDP). And the elections are round the corner!

File picture of a budget presentation in Parliament.

A coincidence?

I am not suggesting any “predictive coding” or a political-economic theory, but it is more than a “coincidence” or at least a hypothesis. A hypothesis can be “either confirmed or rejected” after the research work is done, – in this case, the elections.

The point is, however, achieving a surplus in the primary account has an adjustment cost, which may be politically sensitive. Therefore, it is not surprising that a genuine attempt to reach a primary account surplus can have a political cost so that it may not be politically correct. The electorate seeks “microwave” solutions to their personal issues resulting in a loss of power to the governments with genuine attempts for corrective policies.

Over the past 75 years, Sri Lankans defeated the long-term policies in favour of short-term gains; they defeated the policies that cover the entire nation in favour of personal gains; they defeated the “realistic” policies in favour of “unrealistic” ones. Therefore, it is not surprising that attempts to correct primary account balance were a reason for losing a democratic battle.

We have a set of important questions related to the concept of primary balance. In the first place what is primary balance and why is it so important? And after all, does it have any political implications and, if so, would such political implications change the destiny of a nation?

In addition, surprisingly, not many countries bother about maintaining a primary account surplus. Given this contradictory evidence even from neighbouring countries in Asia, why do we want to push for it at a political cost?

Today, let’s try giving some simplified answers to these fundamental questions.

Today, let’s try giving some simplified answers to these fundamental questions.

Necessary, not sufficient

Primary balance is the difference between government revenue plus grants and expenditure without interest payments. Last year 2023, the government expenditure was over Rs. 5.3 trillion, out of which 46 per cent alone was on interest payments. The balance, 54 per cent expenditure amounted to Rs. 2.9 trillion as non-interest expenditure. The difference between the two, Rs. 173 billion, was the primary balance.

Interest payments are determined by the country’s borrowing costs, reflecting the size of previous budget deficits. A deficit in the primary account means that the country’s debt burden is still on the rise. In contrast, a surplus in the primary account means that the country can manage its expenditure from the revenue without further borrowings.

Maintaining a primary account surplus is a necessary condition for achieving debt sustainability. Given the current debt crisis of Sri Lanka together with suspended debt repayment since April 2022, maintaining a primary account surplus is fundamentally important.

As per debt sustainability arrangements, the Sri Lankan government expects to reduce the country’s debt-to-GDP ratio from 128 per cent in 2022 to 95 per cent by 2032. Although it is not sufficient, one of the necessary conditions to achieve this debt sustainability target is to maintain a surplus in the primary account.

Misunderstanding

Surplus in the primary account does not mean that the country does not need to borrow any more. The country may continue borrowing at least to meet interest payments, which we kept outside the primary account. As per 2023 budgetary numbers, Sr Lanka has to borrow in order to cover the budget deficit amounting to Rs. 2,282 billion (8.3 per cent of GDP).

While achieving a primary account surplus, the Sri Lankan government continued to borrow; during the first quarter of the year 2024, as per Central Bank data, the government’s outstanding domestic debt has increased by 1.4 per cent, but foreign debt has declined by 7.9 per cent.

While achieving a primary account surplus, the Sri Lankan government continued to borrow; during the first quarter of the year 2024, as per Central Bank data, the government’s outstanding domestic debt has increased by 1.4 per cent, but foreign debt has declined by 7.9 per cent.

The point is that technically the government does not have to borrow, unlike it did in the past, to pay for its recurrent and capital expenditure including salaries and pensions, subsidies and transfers, healthcare, education, and social services. The government has also been maintaining some important prices below the costs and covering up losses of state enterprises assisting them to borrow with government guarantees.

Transition time

In the past, the government must borrow even to pay for some of these expenditure items, resulting in a primary account deficit and a continuous increase in debt burden. As we have stated in our opening remarks, the country could achieve primary account surplus only on a few occasions in the past 75 years.

As of now, in spite of achieving a primary account surplus in 2023, however, the country is in a transition period. As per the just concluded bilateral and private debt restructuring, Sri Lanka has received some breathing space. The main elements in the debt restructuring were the extended period of debt maturity, grace period to start debt repayment, ability to issue new bonds to cover the arrears, and a percentage reduction in the debt value.

With all that, Sri Lanka has received space for flexibility for internal adjustments and to continue with strengthening its fiscal operations. How to manage that flexibility in order to prepare for the medium-term debt sustainability and long-term economic progress is, perhaps, the most pressing question that the country must focus on.

An indebted country

For a country that has faced a debt crisis, an achievement of primary account surplus is the first step to improve the credit rating and to win back investor confidence. A positive primary balance signals responsible fiscal policies. Investors and markets view it favourably, leading to lower borrowing costs and increased confidence in the economy.

However, it is time to focus on long-term goals within a broader economic context, without which the primary account surplus may not be able to sustain too long. In this respect, economic growth, trade performance, investment promotion, and income and employment generation are the key areas that need to be managed.

The conclusion of the debt restructuring process is not the end of the story, because it does not solve the country’s indebtedness. Perhaps, a country may start repaying its debt, remaining too long as an indebted country in the world. Debt-to-GDP ratio can be effectively lowered by increasing the denominator – GDP (although it may alter the “haircut” or the reduction in debt value).

The political question

We have already mentioned that achieving a primary account surplus is not a popular policy measure, at least in the short run. This is because it must be achieved through painful policy choices by raising tax revenue and cutting down expenditure, as well as by improving productivity in the public sector.

Sri Lanka achieved some improvements in government revenue by raising both direct and indirect tax revenue, while addressing the latter two policy measures continue to remain a controversial issue. It means that the public has been affected not only by the crisis impact but also by the policy responses to the crisis.

There is no dispute about the fact that tax evasion, tax avoidance and tax exemptions still remain widespread, while cutting down expenditure and improving productivity are key reforms too. Instead of accelerating the reform process, its slowdown or a detour would cost more in the long run. This is the lesson taught by the country’s history of the past 75 years.

(The writer is Emeritus Professor of Economics at the University of Colombo and can be reached at sirimal@econ.cmb.ac.lk and

follow on Twitter @SirimalAshoka).

Hitad.lk has you covered with quality used or brand new cars for sale that are budget friendly yet reliable! Now is the time to sell your old ride for something more attractive to today's modern automotive market demands. Browse through our selection of affordable options now on Hitad.lk before deciding on what will work best for you!