He turned the tale of Sigiriya topsy-turvy

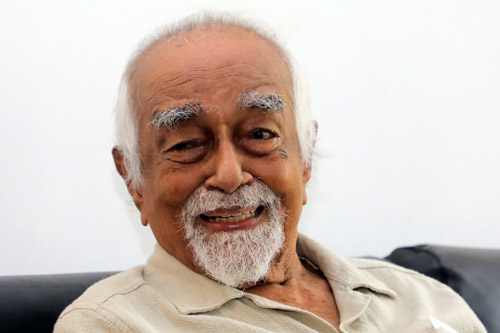

All smiles at the Orient Club, Colombo. Pic by Akila Jayawardena

Polite but point-blank was the refusal to be interviewed, on the grounds that he is no longer a public figure.

The clincher was when told that the younger generation needed a role model, very few and far between these days, who was unafraid to stand true to his convictions garnered through toil and meticulous research.

Grumbling that his arm has been twisted, Dr. Raja de Silva, the first scientist (he was a chemist) to take to archaeology in Sri Lanka, is standing spruce and smart, at the entrance to the Orient Club in Cinnamon Gardens, 10 minutes before the appointed time on July 27.

Dr. de Silva who turns a century (100 years) today, August 4, jokes about why the appointed time was 11.15 a.m. “The bar opens at 11.”

His passion has been the majestic Sigiriya rock and over delicious cutlets and lime juice this invariably becomes our main topic of discussion.

Long before patricide King Kassapa 1 turned his attention to this forbidding rock which rises from the vast plains of Sigiriya, it was the abode of the Mahayana monks, proved Dr. de Silva, meticulously analysing every detail about Sigiriya.

The beautiful damsels in diaphanous attire adorning the walls of the fresco pockets were paintings of the divine Tara and not Kassapa’s queens or concubines, he contended and even published the book ‘Sigiriya Paintings’ replete with minutest detail and stunning photographs in 2009.

What was the outcome when he turned the tale of glory and grandeur of the iconic heritage site of Sigiriya topsy-turvy, we ask, and the prompt reply is that people accepted the theory because mere mortal women had been replaced and displaced by a benevolent Goddess!

This passionate pursuit of a different line of thinking on Sigiriya had begun by chance for Dr. de Silva when he, as an Assistant Commissioner at the Department of Archaeology, was instructed by Commissioner Dr. C.E. Godakumbura to take necessary action after vandals had daubed green paint on the priceless paintings on October 15, 1967.

The fresco pockets had been cordoned off and were out of bounds for all and sundry, fearing more acts of vandalism. Giving permission to access the area was Dr. de Silva’s prerogative and on his second visit to Sigiriya after the vandalism, he had found a couple of people including German swami Gauribala who was living at Dodanduwa in Galle, pleading to be let in.

This swami, earlier a Christian but turned Hindu, who had delved deep into ancient texts had told Dr. de Silva that the Sigiriya paintings were of Goddess Tara. When later he met him again and attempted to probe further, he had been told to “find out yourself”, setting this archaeologist on this quest.

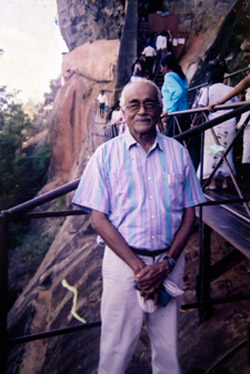

At Sigiriya: His lifelong passion

“As I dug deeper and deeper into literature, evidence emerged that it was indeed Goddess Tara…….the complexion and the ‘mudra’ (a symbolic or ritual gesture or pose in Hinduism and Buddhism, most performed with the hands or fingers) and much more indicating that it was not a mere mortal but divine being,” he says.

Recalling the reaction to this controversial revelation, Dr. de Silva says that two men had tried to approach powerful Minister C.P. de Silva of the then government to kick him out of the Department of Archaeology but the Minister’s brother Dr. L.B. de Silva who was also a chemist like him, had chased them off.

On another occasion when Dr. de Silva delivered a lecture on the same topic at the Organization of Professional Associations (OPA), a senior monk had opined that “history would have to be changed” to which his repartee had been “karanna deyak ne (there’s nothing that can be done)”.

He laughs over the politics of those times……….how he was next in line for the post of Commissioner. Though Cultural Affairs Minister I.M.R.A. Iriyagolle preferred his junior, the Chairman of the Public Service Commission (PSC) had stood firm (by Dr. de Silva).

“However, I retired early, at 53 years and allowed my junior to sit in the coveted chair,” laughs Dr. de Silva.

Our conversation meanders to other stuff, when he says that he is actually not Raja but “Rajendra”, named by his parents after an ancient Chola king.

Down memory lane, he goes – he was the fourth son in a family of six boys and one girl. His father, Dr. Walter T. de Silva, was a government doctor and his mother was Mangala from a big family from the south. As his eldest brother was into chemistry, Raja’s childhood was full of science books, while his father insisted that he enjoy the pleasures of English Literature classics.

Turning in his seat, he points through the door and the window at revered Royal College and how his mother insisted that she would accompany him to school on the first day, even though he could have walked with his brothers from their home down Buller’s Road.

Nostalgia is obvious when Dr. de Silva recounts that his mother did not stop at the gate but marched him into the college’s august 600-seat hall and made him look in awe at the names of Prize Winners down the years, portrayed on the wall.

Both in 1923 and 1924, a Diyasena S. Jayawickrama had bagged the Shakespeare Prize. It was his mother’s brother who had later become a Queen’s Counsel.

“The day you get your name up there,” his mother had promised he would get a bicycle.

“One bicycle please,” he had told his mother, for Raja had indeed won the C.A. Lorensz Prize awarded to one of the top students in academics. The promised bike, all in red, became his.

After Royal College it was straight off next door to the University of Ceylon to dabble in the properties, composition and structure of substances, passing out with a Degree in Chemistry. He had also been the All Ceylon Table Tennis Champion.

His first job had been at the acetic acid factory of the Department of Industries in Madampe but yearning for permanent employment, he had written “like Oliver Twist of Dickensian fame” to his Chemistry Professor “asking for more”. The Department of Archaeology job had just been gazetted and the rest is history.

A specialist Chemistry graduate from the Universities of Ceylon and London, joining the Archaeological Department in 1949, training at the Archaeology Survey of India and obtaining his post-graduate qualification at the University of Oxford after researching the technical aspects of art-history. After retirement, he took on the mantle of advisor to the department on the conservation of cultural property.

One tale, Dr. de Silva picks out from his colourful tenure at the Department of Archaeology……..one day the Commissioner’s peon had passed onto his peon the message that the Commissioner wanted to see him. Having gone home for lunch, Dr. de Silva had walked into Commissioner Senarath Paranavitana’s office at 2.10 p.m., to see him glancing at his watch and stating that lunch-hour was from 12 noon to 1 p.m.

Pat had come the reply from Dr. de Silva, that 1-2 p.m. was nap time which made him more efficient at work thereafter to which Paranavitane had replied: “Is that so?”

Accompanied by a deep-throated laugh, Dr. de Silva describes how Paranavitana had added a new piece of furniture to his office’s anteroom – a weval (rattan) lounge chair just like the one Raja had, most probably for him to take an afternoon nap as well!

Today, widower Dr. Raja de Silva celebrates 100 years of an illustrious life with a lunch for kith and kin, organised by his two daughters who have come from abroad for this special occasion and his son at the Dutch Burgher Union (DBU) at Thunmulla.

“Come visit me in Sigiriya, where my permanent home is,” invites Dr. de Silva, for he will be there, he assures, for the Presidential Election on September 21 to cast his vote.

Just before we bid goodbye, this famous Archaeologist of yore presents me with his “home copy” of ‘Sigiriya Paintings’ autographed then and there by him.

“I will replace this with another book – but this is to ensure that we meet again soon,” he smiles.

Searching for an ideal partner? Find your soul mate on Hitad.lk, Sri Lanka's favourite marriage proposals page. With Hitad.lk matrimonial advertisements you have access to thousands of ads from potential suitors who are looking for someone just like you.