Sunday Times 2

Preserving wonder: The vital role of Colombo Zoo in conservation, children’s lives and urban ecology

View(s):By Arefa Tehsin

It was a sweltering afternoon. We were surrounded by the chatter of excited children, each clutching an ice cream cone as they marvelled at the baby orangutang, lion cubs, and a baby sloth bear. The zoo’s vitality was palpable, evidenced by the successful breeding of these animals in captivity. As the wise old orangutang, the zoo’s central attraction, retreated for rest, we left with a silent promise to return. However, this haven of discovery for millions of children, together with its ancient trees, is under a demand for closure. Once again.

The magic of childhood zoo visits

Most of us have witnessed the thrill of a child on visiting a zoo or being at close quarters with a wild animal. As millions of children flock to Dehiwela Zoo each year, they’re not just visiting animals; they’re forming connections that could shape the future of our planet. The zoo serves as a living classroom, bridging the gap between urban life and the natural world and instilling a sense of wonder that no AI can replicate. To experience the wild through AI is as good as experiencing a holiday through it.

A lion cub, closely watched by the Zoo's well-trained staff, is seen entertaining the visitors

Jerry Mander, in his book ‘Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television’ (comparable to AI now), wrote that after some time, if you ask a child, “Where do oranges grow?” she’ll reply, “In the supermarket.” Most city-dwelling children are suffering from nature deficit disorder.

Many kids from the lower income classes never get to see a wild animal. Zoological parks remain the only place where they can have close wildlife encounters and experience their gestures, smells, noises and calls. It opens a whole new world of curiosity.

According to CEE India’s report, “In India there are more than 150 zoos, and they attract as many as 50 million visitors annually… Zoos’ potential for making people of all ages aware of the threats to the global ecology is unlimited.”

An Indian naturalist’s visit

On Dr. Raza H. Tehsin’s (one of the initiators of the wildlife conservation movement in India) visit, he was awed by the 26-acre zoological garden housing around 250 species, including iconic animals like black panthers and white cobras, and the crowds of visitors thronging the zoo. He met the zoo officials to congratulate them. The animals were well-fed and routinely checked by veterinary staff; mating partners were organised periodically, resulting in the breeding of various species, and the enclosures were species-specific (e.g., pools, climbing frames, hides, nest boxes, plants, and hiding spots).

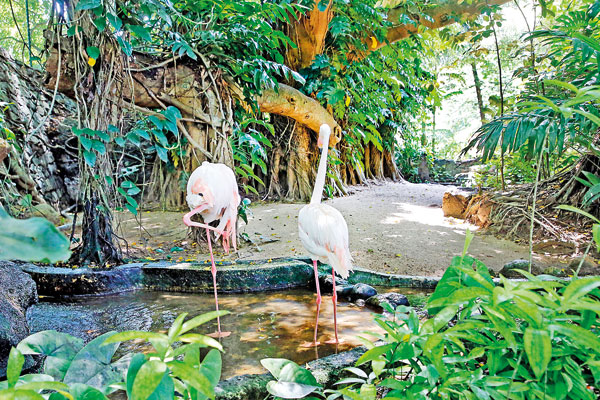

Dehiwala Zoo's flamingos: The conservation work extends much beyond the animals on display

Last 20 years

We have witnessed the zoo becoming only better. The National Zoological Gardens Department, along with the Department of Wildlife Conservation, is engaged in programmes to reduce the density within the zoo and to prioritise conservation. The breeding and rewilding project is focused on endangered, threatened, and endemic species like barb fish and rusty-spotted cats, one of the smallest wild cats in the world. They are also building capacity for a climate change adaptation programme for susceptible species like pangolins.

The conservation work extends much beyond the animals on display.

Young Zoologist Association

A few years ago, we had a large monitor lizard outside our home with its face cut off in half (including the eyes and mouth) by a passing vehicle. The reptile could not feed or see. We waited for its misery to end for 2-3 days and finally called the zoo. A student involved with YZA came to pick up the injured animal. Since he didn’t have money for a tuk-tuk, he came walking two kilometres from the main road, asked for a carton to lift and take the lizard with him, and refused money for the transport back. The monitor lizard continues to survive with dedicated care at the zoo hospital.

The Dehiwela Zoo hospital provides veterinary graduate, undergraduate and voluntary training. It conducts research on preventive medicines, provides surgical treatments and undertakes laboratory investigations.

I have come across several naturalists across the country who have begun their conservation journey at YZA.

Zoos vs. Natural habitats

On a visit to Gal Oya during the rains, we went for a night drive with a naturalist. The tar road, which does not have heavy vehicular traffic, was almost white with the flesh of tens of thousands of frogs, crabs, snakes, snails and other animals that had come out in the rains and were flattened by a few passing vehicles. Among the live creatures, which we picked up and kept on the side, were terrapins and a four-foot-long blue worm. How safe are these “natural habitats” from humans?

The governments of many countries have failed to implement wildlife laws effectively, leaving neither enough forests nor timely action for wildlife crimes. The wild animals need protection from us, many of which are on the brink of extinction due to our enormous horde of 6 billion. We’re facing an extinction rate 1000 times faster than the normal rate of extinction. The causes are overexploitation of natural resources, pollution, fragmentation of habitat and climate change.

Most of the animals that are bred in captivity will not survive if released in the wild. The emphasis on “caged” animals overlooks the fact that much of the natural world has already been lost to human encroachment.

The ethical dilemma?

Critics argue that keeping animals in captivity away from their natural habitats is cruel. This perspective often overlooks the harsh realities of the wild.

We tend to interpret and superimpose human sensibilities (boredom, depression, etc.) on animals. Yes, cruelty is deplorable, and nature/wild should be treated not with equal but greater respect. But what is cruelty? Cruelty is leaving no space for creatures in the wild, building highways, cutting forests for “development,” making no animal crossing on roads—the list is endless. In ‘Was the Buddha a Rationalist,’ Takiri Dissanayaka writes, “When the puritan Devadatta wanted to enforce vegetarianism on the Bhikkhus’, the ‘ism’-free Buddha turned the proposal down… The true intellectually free man can never be a purist in this mixed, never wholly pure world.” Is there cruelty in eating meat or eating vegetables for which forests are cleared (agriculture being the biggest source of habitat destruction in the world) and pesticides used to grow them that kill countless insects and birds each year? How many petitions against these cruelties do we see?

Contrary to common misconception, animals bred in zoos often don’t face mental issues and have significantly longer lifespans. The caretakers treat them with love, risking their lives daily. Not many of us would fancy going inside a cage to feed a carnivore or a ‘masth’ elephant. The hypocrisy of keeping pets while opposing well-maintained zoos often lies in a misplaced empathy that overlooks the complexities of conservation.

While pets are kept for companionship, often confined to homes or yards, zoos aim to balance public education, conservation, and animal welfare. We domesticate animals, making them dependent on us for food and security, take them out on a lease, and decide on their mating choices. Well-maintained zoos, unlike some pet ownership scenarios, are often regulated and focused on ensuring the physical and psychological well-being of animals, contributing to conservation efforts that are essential in a world where natural habitats are rapidly disappearing.

What’s at stake? The broader perspective

Zoos play an irreplaceable role in the conservation of endangered species. The Dehiwela Zoo, for instance, is a hub of ex-situ conservation. It has housed record-breaking animals, such as a giraffe that lived up to 45 years—the oldest in the world—due to meticulous care. The ancient trees and diverse ecosystems within the zoo provide a vital counterbalance to the concrete jungle surrounding it. As urban development encroaches on natural spaces, the zoo becomes increasingly important as a refuge for both wildlife and city dwellers seeking a connection with nature. Moreover, closing the zoo would likely result in the loss of prime property to commercial development.

The Homo sapien—the thinking man—in his great walk towards ‘progress’, invents new philosophies to cover his guilt of ruthlessly destroying nature (donate a dollar with every doughnut for saving dogs). If insects’ blood was red, says Dr. Tehsin, our roads would be bloody every day. We sit on a mahogany chair (a dead tree), sip on a glass of wine (from vineyards made by clearing wilderness), remove our leather shoes (animal skin), cast a glance around our air-conditioned (greenhouse gas) room (built on countless insects and small creatures buried alive with cement), pet our pet, and sigh about zoos, those cruel places that encage animals.

I tend to agree with what Edward Ebby, who strongly advocated for environmental issues, said, “I am a humanist. I’d rather kill a man than a snake.” And I tend to agree that zoos are vital for conservation in the world we live in. If we truly care about wild animals, let’s start with re-connecting their age-old migration corridors, which they have lost due to us, making the parks they live in no different than large zoos. Perhaps that would be a worthy start towards our fight against cruelty.

(Arefa Tehsin is the author of 19 fiction and non-fiction books and an Ex-Honorary Wildlife Warden of Udaipur, India. Her latest book, The Witch in the Peepul Tree, has been shortlisted for The Asian Prize for Fiction.)