Farewell to a musical icon

Rohan de Saram: Earned plaudits from critics, conductors, academics and composers alike

Last weekend, a prominent music journal in the UK, published a short article as an obituary for Rohan de Saram, declaring, ‘British Cello Legend dies, 85’. The notice is not entirely wrong, yet not accurate either!

Few among the people of Lanka have been considered as worthy and held in highest esteem among a global audience comprising those who follow the arts, musical performance, its interpretation, appreciating and understanding the elements involved in mastery of an instrument as Rohan de Saram. He earned plaudits from critics, conductors, academics and composers alike, and was invited to perform for Royalty and before various heads of state.

Rohan also received praise by fellow performers and younger players who benefitted from his teaching and sharing, as he supported various causes, including bringing the work of emerging contemporary composers in various parts of the globe into prominence.

For much of his life as a professional musician and concert artiste, Rohan was based in a suburb near London. His musical education was in Europe, and his performances took him to different centres around the globe, both east and west.

His father, Robert de Saram who studied law and began his career ar Gray’s Inn in London during the 1930s, and mother Miriam Pieris, met and married while in England. Rohan was born in 1939 in Sheffield, and then the family moved to Guildford in Surrey for a few months, when World War II broke out. The small family with their newborn son, hastily travelled back by ship to Ceylon, since the European theatre of war was considered unsavoury for all.

Little Rohan and his parents lived on Ward Place in Colombo. From there, he attended the kindergarten (nursery class) at Bishop’s College Colombo. Later, he was on the roll at S.Thomas’ College Mount Lavinia. Not long after, there were siblings, brothers Skanda, and Druvanand (Druvi) and sister Niloo. The whole family was exposed to and influenced by artistic and intellectual pursuits and this boded well for Rohan’s later development.

Although a lawyer with a practice in his family’s firm in Colombo, Robert de Saram’s passion was music. He was a competent pianist and very interested in the art of composition, avidly studying the books ‘Craft of Musical Composition’ and ‘Elementary Training for Musicians’ by Paul Hindemith. His affinity was toward what might be called ‘Western culture’. Robert’s mother, Myra Loos-de Saram had studied music and piano in Europe, and was an admirer of Grieg. These interests percolated down to Rohan’s mind and heart.

His parents thought it fit to provide lessons in piano to all of their children, and who better than Irene Vanderwall née Sansoni as teacher! Irene was a prodigy and fine performer who had qualified at the Royal School of Music, London. It was she who was responsible for preparing the genius of Lucien Nethsinghe so he could be sent to England for higher studies in music and become an organist of repute. Another of her star pupils is the brilliant concert pianist Malinee Jayasinghe-Peris.

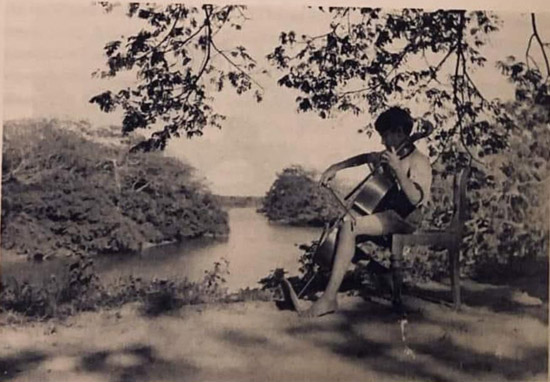

By the banks of the Menik Ganga: 13-year-old Rohan practising the cello during a holiday at Yala National Park

Miriam Pieris, on the other hand, had definite interests in the Oriental arts. Although, her mother, Lady Hilda Obeyesekere was also an accomplished pianist with a penchant for Chopin, Miriam, who schooled at Hillwood in Kandy, was fascinated by the Kandyan dance and its rhythms. She managed to have lessons from Ukkuwa, one of the great dancers of the 1920s, thus entering a sphere traditionally reserved only for males. Miriam was also very involved in the art of the Kandyan drums. She would, later, pass on this fascination to Rohan. Miriam also studied singing and playing violin when in England in the 1930s, when her father, Sir Paul Pieris-Daraniyagala was working in London.

At S.Thomas’ College, Rohan came under the tutelage of the iconic Chaplain Roy Bowyer-Yin, the Cambridge scholar, organist and choir-master. Bowyer-Yin, referred by all as ‘Father Yin’, took special interest in Rohan’s capacity for playing music. Yin would organise lessons in musical appreciation in the evenings, after the end of a school day. Rohan and brother Skanda accompanied by their father Robert, would drive back to school after sundown and spend some hours listening to gramophone recordings and discussing with Father Yin, the music played.

Keeping beat on the Kandyan drum: A passion passed on from his mother Miriam

In this same period, Rohan and Skanda would spend quite some time on weekends and holidays at Nugedola near Pasyala where lived their maternal grandparents, in a fairly spacious property given to coconut cultivation.

In those idyllic days, the brothers would create their own ‘adventure’, going down deep into the plumbago mines in primitive ‘lifts’, going fishing in the ponds, or being spun round and round on the buffalo-powered sekkuwa, (granite mounted-grinder) which crushed the sun-dried copra and extracted coconut oil. Or they would search for the bright-blue eggs of the ‘Babblers’ in their nests in the iron-wood trees, which lined the three-mile dirt track to the house. They would visit the piggery and be chased by the pink pigs when attempting to pluck a ripe jak fruit inside the pen. And, among the special delights would be sampling the freshly drawn sweet-sap of the coconut-palm flower (thelijja) each day, as well as driving the buffalo-drawn cart with oil drums filled with water from the reservoir nearby, to water the plants in the garden around the residence!

These many experiences definitely ‘grounded’ Rohan as belonging on Lanka’s soil.

On matters musical, Rohan’s parents held the idea that there might be ‘another instrument’ that Rohan might be persuaded to try playing. They found in Colombo, a Jewish immigrant named Martin Hobermann who was playing cello in a dance band in Colombo. A refugee from Poland, who had fled Nazi occupation, he had qualified at the Conservatory in Warsaw. Robert and Miriam de Saram were impressed with his skills and capacity as a player of ‘classical’ music.

Miriam kept pressing Hobermann for lessons for her son, but he was not interested in teaching a nine-year-old. After repeated appeals, he relented. Soon, the teacher was impressed by the boy’s rapid progress. Within a year, he arranged for Rohan to perform as soloist at the Grand Oriental Hotel in Colombo in 1950. His first public concert! In the audience that evening was the Governor General of Ceylon, Lord Soulbury, and the first Prime Minister of Independent Ceylon, D.S.Senanayake.

Insisting that this boy was unusually gifted, Hoberman recommended that he should stop at nothing short of being taught by the towering Pablo Casals. The family was not sure that was possible. Ceylon’s economy was in a parlous state, unable to find funds for rice. How could the family afford such things as musical education with Casals? But Hobermann was insistent that no time should be lost in securing an opportunity for Rohan to be taught by a true maestro.

Back at S. Thomas’ College, Chaplain Yin supported the idea that it would be of far greater value to not ‘waste time’ with scholastic studies, and that Rohan would benefit greatly by pursuing his musical studies instead.

Major decisions had to be made. Miriam de Saram decided to follow the advice of Rohan’s teachers. Nothing was going to be easy. Securing auditions was one aspect. Seeking funds or scholarships seemed a barrier hard to overcome. Privilege was conspicuous by its absence. With letters of introduction from various people and prominent cellists, Sir George Dyson of the Royal College of Music, offered a scholarship after an audition. Other scholarships were also sought and a series of auditions set up with much difficulty. Finally, even an audition in the south-west of France, with Casals!

One thing led to another, and finally, the family, at great sacrifice to themselves, decided that the 11-year-old was to be supported to become a musician, and be taught by true masters. A former pupil of Casals, the Catalan cellist Gaspar Cassado, who heard Rohan play when he arrived for concerts in South Asia, said that he would teach the boy free of charge if he came over to Italy, where he was now domiciled. Casals himself suggested that Rohan should be taught elsewhere first, and that later, he would accept him for master classes.

Rohan’s parents took their son over to Florence in Italy, and stayed there enduring trial and adverse circumstances, while he was taught by Cassado.

In time, he progressed to a point where he won a competition, judged by Sir John Barbirolli and Gerald Moore among others. With winning the Suggia Award, Rohan was able to seek master classes with Pablo Casals. Casals said of him, “There are few of his generation that have such gifts”. In the following year, he won a Harriet Cohen International Music Award.

At the invitation of Dimitri Mitropoulos, Rohan was invited to give his Carnegie Hall debut in 1960 with the New York Philharmonic, playing Aram Khachaturian’s Cello Concerto under the baton of Stanislaw Skrowaczewski. Impressed, Gregor Piatigorsky presented him with a special bow.

Snapshot from the past: The brothers three, Skanda, Druvi and Rohan

The accolades flowed from there. While his fame and reputation were securely established with the ‘classical’ repertoire, Rohan also championed new and contemporary music. He was able to travel on these seemingly parallel paths with ease. He was cellist with the leading contemporary ensemble, the Arditti Quartet from 1979 to 2005, and premiered new music by Cage, Glass, Gubaidulina, Ligeti, Rihm, Xenakis and Luciano Berio among many other composers. Even though some of those works and challenges that he undertook with mastering such new material confused certain audiences, he was recognised as a serious musician of stature, because of his versatility.

A special privilege was when Rohan was able to include his pianist brother Druvi in his performing career. They collaborated several times on stage, and were included as a duo in concert programmes and on recordings, one significant recording being Prabandha for cello and piano, especially composed for them by John Mayer.

Ramya de Livera-Perera, the highly accomplished pianist and musician recalls the time she was called upon to play a concert in Colombo with Rohan, a decade or more ago. She admits the challenge was “scary”. She was nervous about playing with such a celebrity. Adding to her apprehension was that they had time only for two rehearsals before the concert. She describes how Rohan calmed her and guided her through the rather unusual tempi of a work by Gaspar Cassado, which was a compliment or ‘tribute’ to Cassado’s teacher, Pablo Casals. Coincidentally both were Rohan’s teachers. Rohan had taken time and effort to explain the rationale for the piece, and how it was conceptualized by the composer, and of the manner in which the piece needed to be expressed at the piano. The piece is ‘Requeibos’.

The other composition they played was Beethoven’s cello sonata op. 69, no 3. Rohan provided the nervous Ramya with the confidence and spirit to turn in a performance that she realized was a cherished opportunity at “making music together”, being equals and collaborators upon a musical canvas.

Another cellist, and conductor of the Symphony of Orchestra of Sri Lanka, Dushyanthi Perera, also refers to a similar experience where Rohan instructed and caringly taught her, how to interpret this same piece by Cassado. With Rohan, there was no display of impatience or superiority, and definitely no histrionics as associated with the prima donna antics that some celebrities resort to.

It is also worth quoting a very young musician and pianist, Johann Pieris, who wrote: “I particularly remember seeing his name in the Oxford Dictionary of Music and thinking how wonderful to know what a great contribution he made to Western Classical music particularly the cello repertoire, its techniques and the 20th century string quartet.

“He studied with the leading cellists of the time, Cassadò and Casals. He worked closely with (Elliot) Carter, Stockhausen, Shostakovich, and Kodály among many other leading contemporary composers.

‘He was definitely not recognized as much in Sri Lanka for his contribution to the contemporary repertoire but I am very fortunate to have at least witnessed him perform in close proximity. Farewell!”

In December 2004, Rohan de Saram was awarded an honorary Doctorate of Letters (D.Litt.) from the University of Peradeniya. In December 2005, he received the Deshamanya, a national honour bestowed by the President of Sri Lanka.

Rohan had made it his guiding principle that any musical performance that he would present in Sri Lanka, would be gratis. He would accept no payment or gratuity, rather, would consider it his due to bestow a gift upon what he considered his natural inheritance in the land of his fathers. His passport was British, but his spirit resided in Lanka.

Rohan leaves behind his wife Rosemary, daughter Sophia and son Suren.

Searching for an ideal partner? Find your soul mate on Hitad.lk, Sri Lanka's favourite marriage proposals page. With Hitad.lk matrimonial advertisements you have access to thousands of ads from potential suitors who are looking for someone just like you.