Keeping memory alive: The exhibition on Malaiyaga Tamils shows the need for justice

A fistful of earth tied to a corner of a sari pallu hangs as one of the exhibits in the old Matara courthouse. This display was recreated by Sujata, a welfare officer at Oliphant Estate in Nuwara Eliya, inspired by a story among the Malaiyaga community. During the forced repatriation of Malaiyaga Tamils from Sri Lanka to India in the 1970s and 1980s, some women would take soil from the land of their birth, Sri Lanka, to in effect consecrate temples they made in India. This speaks of the powerful emotional tie to the country from which they were forcibly uprooted. This precious earth from a kovil was believed to have curative properties.

At a time when colonial histories are being widely re-examined and historical narratives energetically contested across the world, the Malaiyaga Tamils have mostly been confined to a footnote. ‘Is the tea plant a tea bush or a tree?’ asked Velusamy Weerasin-gham, who was moderating a discussion on the Malaiyaga community last weekend in Matara, part of a series of events curated by the Collective for Historical Dialogue and Memory around the exhibition, ‘Rooted: Histories of the Malaiyaga Tamils’. Some say a bush. But it is a tree, he corrects them, making a broader point.

“The Malaiyagam is symbolic of this. The colonial Raj and majority communities pruned the plant aggressively to extract the maximum yield, but, if given the right conditions, we can also blossom into a healthy tall tree,” he says. The term ‘Malaiyaga’ means ‘from the hills’ and was introduced in the 1950s when they were still referred to as ‘kallatoni’ or illicit boat people. The term Malaiyaga acknowledges their roots to the land.

The singer T.M. Krishna in an article in late September recounted meeting a young Malaiyaga Tamil writer who regarded the long-used official categorisation of Indian-Origin Tamils “as a bane; (that) only placed them in no-man’s land.”

Inevitably, while viewing the exhibition, debates sometimes arose with members from the majority community over the term ‘plantation workers’ or ‘estate workers’ to refer to the Malaiyagam. A panel at the exhibition duly addressed these issues, going back to derogatory terms used for the community and how it is necessary to change. Even today, many people in Sinhala and English use ‘wathu demala’ or ‘estate Tamils’.

The idea of holding an exhibition to mark 200 years of the arrival of the Malaiyaga Tamils was conceived by CHDM in late 2022. The first recorded effort to introduce Indian labour on plantations here was in 1823.

Collaborating with the Institute for Social Development and the Tea Plantation Workers’ Museum and Archive in Gampola, CHDM was able to display artefacts such as the kambili (blanket) and thappu (frame drum) that represent a sense of belonging for the Malaiyaga Tamils. A session with leading Malaiyagam academics and professionals provided feedback on the exhibition’s framework, especially to highlight the community’s own efforts to demand rights as opposed to being viewed as passive victims. With the support of ISD, CHDM joined a workshop in Hatton in March 2023 with poets, journalists, teachers, public servants and activists and documented their memories of these objects.

Last weekend, a group of young cultural artists from Nawalapitiya performed with the thappu. This drum was used by the first migrants to ward off wild animals as they made a perilous journey of 150 miles to tea plantations, carrying bundles of tamarind rice and basic provisions that suggested they expected the journey to be much shorter. Thappu player Moses Suresh, 28, and the others in his group are former students of the Kandaloya Tamil Maha Vidyalaya, whose inspiring principal is Yatiyantota Karunagaran. The school actively encourages students to embrace Malaiyagam cultural heritage, learning folk songs and organising street dramas.

Suresh and his friends are completing their university education at the Eastern University in Batticaloa, a huge achievement given that members of the community still struggle to be on par with national educational attainment levels. When they light-heartedly demonstrated beats of a deity-possessed man, the deity delivered a message through the medium: “It is your…duty as educated youth…..to preserve…..this heritage for the future.”

Voices of the community such as Karunagaran were presented through an audio-visual installation to reinforce that Malaiyaga Tamils have also risen to become lawyers, award-winning writers, engineers, businessmen and tea-tasters.

In taking the exhibition to Nuwara Eliya, Colombo and now Matara over the past year or so, we have seen that it evokes a range of emotions. One person, aged 65, said sounds could also trigger haunting memories; Oppari Kochchi, or the lamenting coach, was the sound of steam engine trains that was associated with the painful separations of families due to repatriations to India.

The overwhelming response, however, was that many visitors were not aware that the histories of the Malaiyaga were so intertwined with the history of the nation. A young Malaiyaga woman wrote, “I was born and raised in Sri Lanka but stuttered with tears to learn about my ancestors’ journey. Even though they tried so hard to give us a good life, we are still in the same hardships.”

Another visitor to the Colombo exhibition put it, “We are aware of slavery in terms of what happened in Britain and America, but our history books have nothing to show what happened on our own soil.” CHDM hopes to take the exhibition to more cities, including Jaffna, in the next few months.

One huge positive is that in 2024, the community will have the option of identifying themselves as Malaiyaga Tamil on the Sri Lanka census for the first time. But, the need for societal change has a long way to go. Almost two-thirds of the Malaiyagam still live in line rooms, originally constructed during the colonial period with a single source of water and communal latrines. Land distribution measures for the most part were not extended to the community. Groups from the community are in conversations to include their history in textbooks. A public apology by both India and Sri Lanka for the forced repatriation would be a step towards redressing historical wrongs.

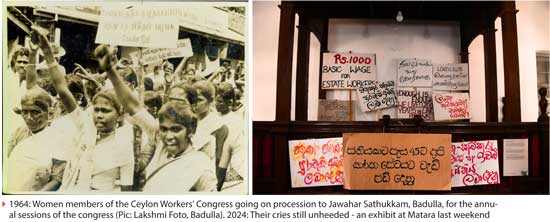

Coincidentally, protest posters bearing slogans from earlier years to recent times were placed along the judge’s seat in the Matara courthouse, a metaphor for the community’s continued need for justice.

(Johann Peiris works for the Collective for Historical Dialogue and Memory and was part of the curatorial team of the exhibition)

Searching for an ideal partner? Find your soul mate on Hitad.lk, Sri Lanka's favourite marriage proposals page. With Hitad.lk matrimonial advertisements you have access to thousands of ads from potential suitors who are looking for someone just like you.