Sunday Times 2

Rising to power: Lanka’s third woman premier and gender politics

View(s):By Shyama Basnayake

The appointment of Harini Amarasuriya, a social anthropologist, PhD holder, and women’s rights activist with a background in humanitarian work, as Sri Lanka’s third woman prime minister, marks a significant moment in Sri Lanka’s political history.

Her appointment has fired the public imagination and has earned admiration and respect across the nation, with social media images capturing her in particularly poignant moments—carrying her own umbrella, greeting a child at eye level, and sitting on the floor surrounded by Muslim women. These moments highlight her approachability, empathy, and a new political culture never experienced previously by the Sri Lankan public.

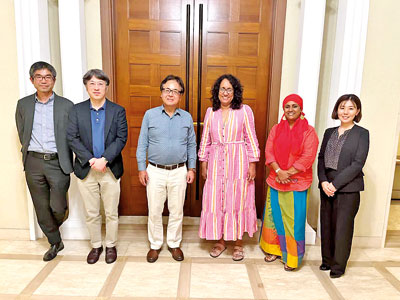

Prime Minister Harini Amarasuriya seen at the residence of Japanese Ambassador Mizukoshi Hideaki (on her right) for a dinner at the invitation of the ambassador

When Dilith Jayaweera—another presidential candidate in the recently held election and a business and media tycoon who positions himself as a Sinhala nationalist—criticised Harini for not conforming to traditional expectations of Sri Lankan women—particularly regarding marriage and childbearing, which he claims are cornerstones of Sinhala civility—it sparked a widespread backlash against Jayaweera, with many people viewing him as outmoded in his thinking. This outrage at Jayaweera’s sexist comments indicates a significant shift in societal attitudes toward women’s roles and identities in Sri Lankan public life and social life generally.

Harini is someone who certainly marks a significant break from the mould of the ‘typical’ Sri Lankan woman as defined by conservative standards. In a society like Sri Lanka, where a woman who strays from the ‘typical’ is often bullied, marginalised, and ultimately silenced (a fate that befell Nathasha Edirisooriya, a young female standup comedian who was vilified as a threat to Sinhala Buddhist culture), it is worth asking what led a majority of Sri Lankan society to accept Harini—a quintessentially ‘atypical’ woman—as prime minister without question. Is this the beginning of a new era in which all women have the luxury of breaking away from tradition without facing social obliteration?

While it is important to celebrate Harini’s rise to power, we must also question what this moment truly means for the women of Sri Lanka in general. There is no doubt that her appointment significantly bolsters the women’s movement and the ongoing struggle for equality in Sri Lanka. As a feminist activist, her position symbolises renewed hope for the empowerment of girls and women across the country. But we must ask whether this newfound social acceptance of the atypical woman is something that applies to Harini as an individual or something that has the potential to have broader social resonance for all women, regardless of their class, ethnicity, and religion.

For instance, has the empowerment signified by Harini’s appointment the potential to reach a female trade union leader in the free trade zone or a garment worker on the factory floor? Can it reach the average Sri Lankan mother in her home? Will this acceptance extend to Tamil women fighting for justice for their disappeared children? Or to Muslim activists working to reform patriarchal marriage laws? Would it apply to non-English-speaking women from lower social strata possessing qualifications, experience, and values similar to Harini’s?

Harini’s success is monumental, but its true impact will be measured by whether it can open doors for all women, regardless of their social status, background, or ethnicity.

A cartoon by renowned political cartoonist Awantha Atigala in the ADA newspaper depicts Harini’s appointment, with a large female gender sign within which a group of women are huddled together, while Harini breaks out from the other end victorious. It raises a thought-provoking question: Why aren’t the other women following Harini and breaking free? Why are they still confined within that circle? Whether an oversight or a deliberate message from the artist, this portrayal prompts reflection on whether Harini’s breakthrough represents an individual success or signals broader liberation for all women. Whatever the artist’s intent, the cartoon serves as a reminder that much work is needed to ensure that this victory becomes a collective one for all Sri Lankan women.

A pattern of privilege

If we examine the three women who have held the highest political offices in Sri Lanka—Sirima Bandaranaike, Chandrika Bandaranaike, and Harini Amarasuriya—there is an undeniable commonality: privilege, both social and educational, and family political connections. Sirima and Chandrika attended St. Bridget’s Convent, while Harini went to Bishop’s College—elite schools that reproduce social and cultural capital. Beyond their education, all three come from bourgeois backgrounds and have political connections. Sirima and Chandrika were part of the Bandaranaike political dynasty, and Harini, too, has notable political ties in her extended family. Despite Harini’s entrance through a leftist, progressive platform like the National People’s Power—a coalition built around the JVP, a party that has a radical Marxist history and staged two militant insurrections in the 1970s and 1980s—the party’s patriarchal power structure remains largely intact, and her role often aligns with these dynamics. This positions all three female leaders in Sri Lankan political history as figures placed within, rather than disrupting, the patriarchal structures of power in Sri Lanka.

This pattern underscores a critical aspect of the gendered nature of Sri Lankan politics: as a society, it has yet to fully envision or embrace female political leadership that disrupts the status quo. Instead, there remains a reliance on the archetype of the elite, educated, aristocratic, sari-clad, well-mannered ‘lady’—one who, while exceptional, still comfortably fits within existing patriarchal frameworks. Such leadership does not necessarily challenge the foundational structures of power. This reflects a deeper societal reluctance to accept women leaders who defy the patriarchal system, stifling the potential for a transformative, grassroots feminist movement capable of addressing systemic inequalities and providing a more inclusive vision for women’s political representation.

Breaking the mould:

Moving beyond symbolism

Harini has shifted the traditional political narrative by breaking away from the stereotypical image of the Sri Lankan woman who has historically dominated Sri Lankan female political leadership. However, this shift needs to be pushed beyond symbolism. It has to move towards overcoming entrenched upper-class dominance in women’s politics, creating genuine opportunities for women from all social and ethnic backgrounds to ascend to the highest positions of power. For real progress, women’s political leadership in Sri Lanka must reflect the current diversity seen in men’s politics.

Achieving this requires not only an inclusive political vision but also systemic changes that dismantle barriers preventing marginalised women—whether rural, working-class or from ethnic minority backgrounds—from fully participating and leading in the political arena. Only when women from diverse backgrounds and experiences can assume leadership roles will Sri Lanka begin to truly realise inclusive political participation for women. The ultimate goal must be to ensure that political power is accessible to all women, regardless of class, ethnicity, privilege, or patriarchal endorsement.

The patriarchal ‘helping hand’?

A cartoon by Namal Amarasinghe, another popular political cartoonist in Sri Lanka, published in the Daily Mirror depicted Anura Kumara Dissanayake—the newly elected president—offering a ‘helping hand’ to Harini as she ascends a perfectly built, red-carpeted staircase, while an adjacent, nearly impossible-to-climb staircase—marked with a female gender sign—sits neglected. Whether the artist intended to celebrate her appointment or highlight the conditions that facilitated her rise, social media widely interpreted this as a positive representation of Harini’s political ascent. This interpretation feeds into androcentric narratives that see women’s achievements as gifts from a benevolent male hierarchy, entirely missing the significance of her appointment. It undermines her accomplishments as a political activist, implying that she needed a patriarchal ‘helping hand’ to reach the top and implies that she did not face the same challenges as other women navigating rough, uneven paths to success.

Such portrayals reinforce damaging stereotypes and obscure the reality of women’s struggles and resilience in politics. Harini did not ask for, nor was she dependent on, any benevolent patriarchal gesture to become Prime Minister. Her rise to power is the result of years of hard work, standing with the right people on the right side of history, and fighting for the right causes. It’s the result of spending countless hours travelling across Sri Lanka, advocating for change, and demonstrating independent political wisdom and a vision that left the political landscape no choice but to pave a path for her. Reducing her achievements to a narrative of patriarchal munificence overlooks her political activism and dedication. Harini’s leadership is not a gift from patriarchy—it is the outcome of relentless commitment to democracy, justice, and good governance.

The paradox of gender and

glass in Sri Lankan politics

An overlooked aspect of Harini’s appointment is the contradictory way men and women are perceived in Sri Lankan politics. Anura Kumara Dissanayake’s rise to the presidency is celebrated as a triumph of non-elite politics, symbolising a transfer of power from the upper echelons of society to the grassroots. Yet, female political leadership remains dominated by those from privileged backgrounds, with power concentrated among a select few. From Adeline Molamure—the first woman elected to the legislature and a fellow Bishopian like Harini—to Sirima Bandaranaike, Rosy Senanayake, and now Harini Amarasuriya, female leadership has largely remained confined to women from privileged circles.

This is not to say these women are undeserving, but it underscores a troubling pattern within a male-dominated structure where power is only extended to women deemed acceptable within the framework. Rather than celebrating the empowerment of all women across classes, the system selectively allows a few to break through, perpetuating the idea that female political leadership is still a privilege of those at the top end of the social hierarchy. The patriarchal culture accommodates women in influential political roles only if they belong to a certain social circle, even bending its own rules to accommodate them.

For instance, starting with Agnes de Silva (née Nell; 1885-1961), a Burgher political activist (not the favoured Sinhala Buddhist woman typically preferred by the political patriarchy) who was instrumental in securing franchise rights for women in Sri Lanka; then Chandrika Bandaranaike, President of Sri Lanka from 1994 to 2005, known for her unconventional lifestyle; and now Harini Amarasuriya, who defies the image of a traditional Sinhala Buddhist womanall were accepted in the political arena despite not aligning with traditional expectations, but only due to their privileged class status. This flexibility, reserved for a few, does not stem from progressive values but rather aims to protect and perpetuate a chauvinistic political agenda. It is paradoxical that while Sri Lanka celebrates Anura Kumara Dissanayake’s rise as a victory for non-elite politics, the same society struggles to envision a woman from a similar background at the top of political leadership. The inconsistency lies in celebrating grassroots progress for men while limiting women’s leadership to the elite, reinforcing a hierarchical system resistant to genuine egalitarianism.

Towards true equality

Although we have every reason to celebrate Anura Kumara Dissanayake’s victory as a historic conjuncture in Sri Lanka’s non-elite politics, we must recognise that we are only halfway there. To achieve full equity, we must see a transfer of power to women from all walks of life, not just the upper echelons of society. The complete dismantling of elitism in politics will occur only when leadership is accessible to women from every stratum, including those at the margins. If not, the concept of dismantling elitist politics will remain a confused middle-class dream—a vision that celebrates ‘people’s politics’ while secretly aspiring to maintain a culture of privilege and elitism.

This half-revolution highlights the inconsistency of those who champion non-elite progress for men but fail to demand the same for women, particularly those from marginalised communities. Dr. Harini Amarasuriya’s appointment undeniably marks significant progress, but the struggle for women’s emancipation is far from over. To achieve a truly inclusive social democracy, the journey toward genuine equality must continue. There must be a relentless push forward, ensuring that the women’s movement in Sri Lanka breaks every barrier until all women experience unhindered equality across social and economic lines. The work ahead is challenging, but it is essential to create a future where every woman, regardless of her background, class, or ethnicity, has the opportunity to lead and thrive.

(The writer is a feminist activist and researcher)