After the storm

The month of September every year brings with it a great deal of conversation about suicide prevention. Our social media is flooded with information about risk factors, warning signs, restriction of means, etc, in the context of prevention and frequent reminders to reach out and seek help in connection with intervention. We are reminded that ‘we matter’ and that ‘we are not alone’, and helpline numbers go viral.

As time passes, our consciousness is occupied with other pressing concerns, and the narrative gradually comes to a halt, until next year. However, there are embers that remain of the dying flames, searingly hot, in the lives of those who experience suicidal thoughts and feelings, of those who have survived attempts at taking their own lives, and those bereaved by suicide. While mitigation and intervention are widely addressed on social media, and in our health systems, a vital cog in the wheel of prevention is severely neglected in Sri Lanka; and that is postvention.

Postvention is an organized response in the aftermath of a person taking their life, where healing and recovery is promoted while mitigating negative effects of exposure. It is an integral part of prevention, where practical social support in the immediate aftermath and long-term support is offered to prevent future suicides from occurring, especially in those who are already vulnerable and are at risk. It involves acknowledging the fact that bereavement as a result of suicide might be complicated in nature, and that it would be experienced differently than when losing a loved one or a friend to other causes.

Survivors of suicide loss are often left with fundamental beliefs around safety, predictability and control being shattered, and with ‘why’ questions and questions around responsibility for which seeking answers may be a challenging process. Feelings of anger and rage, guilt and shame, abandonment, groundlessness and disbelief are some of what survivors may experience, while there is a strong need to seek explanations and reasons for the death of their loved one. There is a process of profound meaning making and other existential questions that a survivor may grapple with, not excluding spiritual questions.

Survivors of suicide loss are often left with fundamental beliefs around safety, predictability and control being shattered, and with ‘why’ questions and questions around responsibility for which seeking answers may be a challenging process. Feelings of anger and rage, guilt and shame, abandonment, groundlessness and disbelief are some of what survivors may experience, while there is a strong need to seek explanations and reasons for the death of their loved one. There is a process of profound meaning making and other existential questions that a survivor may grapple with, not excluding spiritual questions.

The complex nature of suicide often means that there is no one single factor that might contribute to a person taking their life, and therefore no socially consensual answers. This when coupled with speculation, blame, rumors and gossip spread through mainstream media and social media, can bring excruciating pain to those bereaved by a loved one ending their life.

The grieving process that one goes through after a tragic loss like suicide, is often disenfranchised in our society, where there is no public acknowledgement of one’s grief, one’s grief may not be seen as valid, and friends, neighbours, extended family members etc may be unsure of how to support the bereaved, uneasy about what to say and do. The already existing stigma and taboo around suicide may cause a wall of silence to shroud the bereaved, as the initial days after a loss passes by.

Therefore, effective postvention involves us staying close to the bereaved, not just in the initial phase after their loss, but for the long haul. Avoiding asking for explanations, and refraining from providing hollow reassurances like “at least they are not suffering anymore” is crucial. Acknowledging their pain, and understanding that different people may need different forms of support at different times can contribute to constructive postvention.

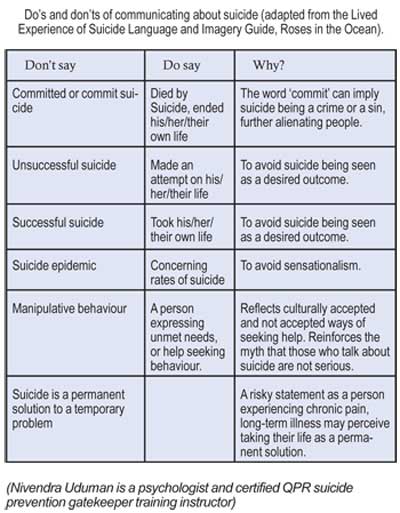

Language matters! The way we talk about suicide plays a vital role, as it has the potential to wound or heal, disenfranchise or empower, defeat or motivate, especially for survivors of loss. Roses in the Ocean, the national lived experience of suicide organization in Australia, created guidelines for communicating about suicide through consultations with those with lived experience. Lived experience of suicide can be understood as having experienced suicidal thoughts, survived an attempt at ending one’s life, caring for someone through a suicidal crisis or having been bereaved by suicide.

Using non-judgmental, compassionate language when speaking about suicide, while avoiding the sharing of graphic details, images of locations, and methods can promote prevention, and lessen the negative effects of exposure. Being mindful not to provide simplistic reasons for someone ending their life, as it can put other vulnerable people at risk, is another powerful way to promote prevention through postvention.

The media reporting suicide in an ethical and responsible manner while promoting help seeking behaviour also contributes to postvention efforts. There is also a need for law-enforcement personnel, emergency medical personnel, coroners, funeral directors, hospital staff, school administrators and human resource personnel to be provided training in postvention, so that they can provide immediate support to the family and loved ones of the deceased.

Schools and organizations require robust postvention action plans, where trained mental health professionals establish contact with students, employees and their families. Finally, posts on social media, text messages, etc reminding people to speak up and reach out, puts the onus solely on the person needing support, whereas we all have a collective responsibility to reach in and offer support.

In the context of reaching in and offering support, an important segment of our population that often falls through the cracks in the health system and beyond, are suicide attempt survivors. It is of great importance that we look through a critical lens at the support and follow-up that is offered through our health services for those who have survived non-fatal attempts at taking their lives. While a common belief is that an attempt survivor would have ‘learnt their lesson’ and therefore will be safe in the future, the effects of stigma, shame and guilt coupled with potential rejection by family, friends and the community, can create further isolation. This can then increase the risk of suicide in the future.

We need to take a long hard look at our policies and systems, and start closing some of the taps that are leaking rather than only mopping the floor. There is learning to be had by listening to those who have survived non-fatal attempts at ending their lives, and those bereaved by suicide. We can and must do better.

| Helpline numbers | |

| Sumithrayo: 0112696666/0112692909 (9 a.m.-8 p.m.) 1333 Crisis Support Service (24 hrs) Lanka Life Line: 1375 (24 hrs) National Mental Health Line: 1926 (call and text, 24 hrs) |

Searching for an ideal partner? Find your soul mate on Hitad.lk, Sri Lanka's favourite marriage proposals page. With Hitad.lk matrimonial advertisements you have access to thousands of ads from potential suitors who are looking for someone just like you.