Sunday Times 2

Truth and reconciliation: The South African model

View(s):By Shehan Ratnavale

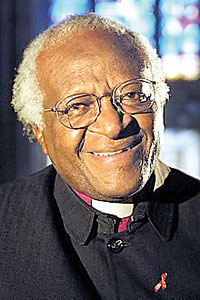

With tense music and a helicopter landing at Ballywalter House in Northern Ireland, the documentary “Facing the Truth” begins like a thriller movie. But instead of a villain or a secret agent, the passenger is Archbishop Desmond Tutu described as ‘the world’s greatest champion of truth and reconciliation’. The documentary relates his role in guiding victims and perpetrators of the Northern Ireland conflict to face the truth and reconcile.

Tutu was chairman of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), a model that has inspired similar commissions in countries such as Nigeria, Ghana, Sierra Leone and Canada. The Canadian Truth and Reconciliation Report, for example, has used TRC-type story-telling to address the traumas of indigenous Canadians in aboriginal residential schools.

Left to right 1996: Chairperson of the Constitutional Assembly Cyril Ramaphosa, President Nelson Mandela and Constitutional Assembly Deputy Chairperson Leon Wessels

TRCs, by their nature, arouse controversy and contention. The International Commission of Jurists has described Sri Lanka’s bill to establish such a commission “as more of a legislative manoeuvre aimed at deflecting the attention of the UN Human Rights Council … than a genuine accountability measure.” The UN Human Rights High Commissioner Volker Turk seemed to endorse this with his observation that: “The environment for a credible truth-seeking mechanism remains absent.”

Archbishop Desmond Tutu

A credible truth-seeking mechanism is viewed by some as essential for Sri Lanka to come to terms with its past. Closure is believed imperative for those unaware of what happened to their loved ones, as well as justice for war crimes and healing by giving victims a voice. Others see such objectives as a combined diaspora western governments’ project motivated by electoral concerns, and even a ruse to criminalise a military who rescued Sri Lanka from terrorism. The hypocritical silence if not tacit support of many of the same nations at the genocidal mayhem launched by Israel in response to the savagery of the October 2023 Hamas attacks, gives aspects of this notion some credence.

While prompted by the UNHRC’s recent observations on Sri Lanka, this article is not written to sit in judgment. It is to specifically understand the South African approach which has been studied by successive Sri Lankan Governments and is also viewed as something of a gold standard internationally. Accordingly, I interviewed Dr. Leon Wessels who served as Cabinet Minister in F.W. de Klerk’s last apartheid Government and testified before the TRC. He is also a lawyer, activist and political commentator.

Dr. Wessels, we are privileged to

have your insights. Can you specifically explain your involvement with South Africa’s TRC?

When former President F.W. de Klerk appeared before the TRC, he asked me to accompany him. He told the commission that neither he nor his cabinet colleagues were guilty of gross human rights violations. Subsequently, I was invited to appear to share my thoughts. I said I would not condemn policemen or soldiers who had committed violent unlawful acts as we were on the same side and fought to maintain law and order as we saw it to ensure that South Africa was not ungovernable. However, I differed from de Klerk as I said I don’t believe the political defence of ‘I did not know’ is available to me as in many respects I did not want to know. I had my suspicions but no facts to substantiate. I didn’t have an investigative mindset and lacked the courage to shout out my suspicions from the rooftops.

I understand amnesty for state crimes was part of South Africa’s negotiated settlement. Would a restorative justice mechanism like the TRC have surfaced if it was not?

This is a good question. I don’t believe a restorative justice mechanism would have surfaced if it was not, so let me explain.

The notion of a TRC and amnesty for state crimes arose during the negotiation process. There were extreme views around with some groups seeking vengeance and others seeking to forget. Typically, victims seek vengeance and the perpetrators want to forget. What enabled the restorative justice outcome is the extraordinary situation where during negotiations between the Government and the African National Congress both perpetrators and victims sat side by side to reach a settlement.

Of the TRC’s three committees – reparations, human rights and amnesty, the latter is the most intriguing. Can you explain the amnesty granting process?

The person seeking amnesty will need to make a public appearance and show that his wrongdoing was politically motivated. The crimes committed should be proportional to the politically motivated instruction. They would need to reveal the truth and there must be full disclosure of the crimes committed. There have been cases where people have revealed some crimes but not all, and have therefore been referred to the National Prosecuting Authority. As per the act, the crimes for which amnesty is sought should have taken place between March 1960 and May 1994.

Testimonies of victims, and accounts of gruesome killings by those such as Dirk Coetzee seen on the online video “Desmond Tutu and the TRC” make one’s stomach churn. While one can understand how Dirk Coetzee fits the TRC amnesty criteria, how were such amnesties received by the country as a whole?

Opinion is still divided on this and some would say that having fitted in with the amnesty criteria, perpetrators of horrific crimes such as Dirk Coetzee leave the scene unpunished. By way of background, I must explain that when the TRC bill was introduced it was challenged in the constitutional court. During the judicial process, one of the judges made the point that if the bill was not passed the truth would never surface even though the perpetrator might leave unpunished.

Also, for the first time victims had a voice and could prevent the amnesty if they proved the perpetrator was not telling the truth. Further not everyone sought punishment. For those who were granted victim status reparations were paid out. Their children’s education in most cases was provided for and those involved in the liberation struggle often received appropriate memorialisation.

President Mandela appointed Archbishop Tutu chairman of the TRC. How pivotal was his character and outlook to the outcomes of your TRC process?

Most important with this choice was that Archbishop Tutu had struggle credentials. His commitment and role in the fight against apartheid was unquestionable and he was widely respected. He didn’t want to forget the past and believed it needed to be addressed for healing to take place. At the same time, he was not legalistic nor was he a vindictive person. That’s why President Mandela appointed him as chairman and that’s why he was pivotal.

What do you see as the main benefits the TRC brought to your country?

I see the biggest benefit it brought South Africa was for the country to know the reality of its past. A country must know its history. The conflict was a hard-fought struggle and depending on where you sat with respect to the conflict you had a selective picture of the past. The TRC opened up all of that. Disclosure of the horror stories was important to enable reconciliation to happen. In the sense that the wounds had to be opened and disinfected for healing to take place.

Finally on global applicability, Archbishop Tutu’s statement:

“here is something, there are mistakes, there are achievements, choose what may be of use to yourselves,” underlines that

TRCs should be context-specific. What would be your advice to countries seeking to learn from South Africa’s TRC model?

This is an extremely difficult question. One has to first understand the dynamics of South Africa to understand the South African model. One has to mould something given the history and expectations of the particular country seeking to develop a TRC.

I have been exposed to international situations where TRCs have been considered and I believe you can’t simply cut and paste aspects of the South African model. The country establishing a TRC needs to be conscious of its particular situation, its history, its society and its aspirations.

Dr. Wessels many thanks for your thoughtful responses.

(The writer works for Softvil Technologies and was a former High Commissioner to Singapore and South Africa)