News

Little or no monitoring of Child Development Centres a serious threat to children’s safety, report reveals

View(s):By Mimi Alphonsus and Dilushi Wijesinghe

The escape of nine girls from a state-run child care institution in August this year has raised concerns about abuse in children’s homes. Deputy Inspector General of Police (DIG), Children and Women Abuse Investigation Range Renuka Jayasundara stated: “Every year, statistics have shown that some children who are abused in their homes are repeatedly abused in Child Development Centres (CDCs) again.”

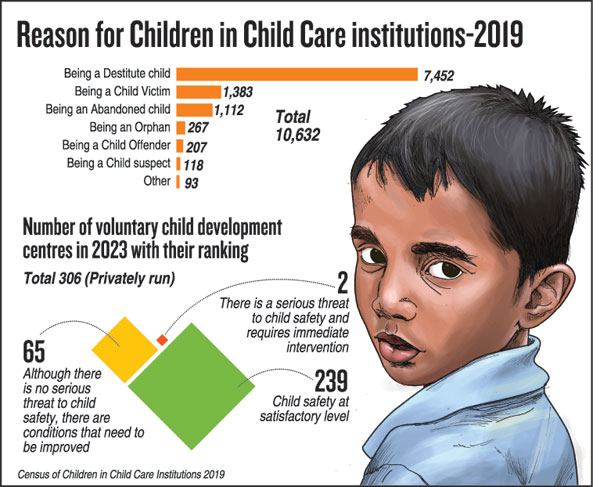

A 2019 census revealed over 10,000 children live in CDCs, placed there by the Probation Department. Some children are orphaned while others have abusive, neglectful or destitute parents. These children wind up in CDCs falling under the Provincial Commissioners of Probation. There are 306 privately-run (voluntary) CDCs and 42 state-run facilities.

In April 2024, a Committee to Monitor the Implementation of Child Protection Measures, appointed by former President Ranil Wickremesinghe, released a 190-page report with disturbing insights into the world of CDCs.

The report found that not all CDCs conduct thorough background checks putting children in danger. “Medical professionals have alerted the Committee to instances where individuals alleged to be paedophiles have attempted to join the staff of CDCs,” the report reads. The committee recommended that the National Child Protection Authority (NCPA) maintain an offender registry to ensure proper screening.

Other issues include a shortage of staff, lack of personalised care, no proper attention to mental health, disruptions to education, developmental delays, and very little attention to reintegration of children into society. Insufficient documentation is another key issue as children struggle to obtain documents such as birth certificates and permanent addresses that they will need in adulthood. Children are often re-traumatised and re-victimised in these institutions and are stigmatised in school and in the workplace later on.

Monitoring

A key reason for the poor and often dangerous conditions in CDCs is insufficient state oversight. Dr. Hemamal Jayawardena, a member of the committee and a Child Protection Specialist at UNICEF said that the NCPA should prioritise monitoring, which is not the case currently. “They are the only authority with the right to enter any child care institution from CDCs to juvenile detention centres,” explained Dr. Jayawardena, “but they focus more on educational programmes which any other department can do.”

Indeed, in the Rs. 40 million budget allocated to NCPA for 2024, only Rs. 700,000 has been allocated to monitoring private CDCs. For reference, NCPA’s “Advocacy, Awareness & Training programmes on Violence Against Children” is allocated more than double this amount.

Troublingly, the committee found that some institutions are simply not monitored at all.Due to a misunderstanding of their legal mandate, NCPA has not been monitoring state-run child care institutions at all. According to NCPA they have rectified this mistake this year.

Another major gap is the lack of NCPA monitoring in religious institutions, even when children are living there. This is concerning given that according to the report, between 2018 and 2022 there were 506 child abuse complaints in religious institutions. In the vast majority of cases–488–the alleged abuser was a Buddhist monk, pointing to the dangers that come specifically with residential religious establishments for children. The committee recommended that the government establish “District-Level ‘Pirivena’ Institutions for the Ordination of Young Monks” and monitor them with the NCPA. The committee has suggested that this apply to all institutions that enrol children for “residential religious study.”

Voluntary, private CDCs, where 88% of institutionalised children are resident, are monitored by the NCPA. Rasika Hegoda Arachchi, the main coordinator for private CDC monitoring at NCPA, explained the process. District and Divisional child protection officers inspect CDCs using NCPA guidelines in the last quarter of each year. Asked whether a set monitoring period might compromise the inspection Mr. Hegoda Arachchi said, “We don’t tell anyone an exact date so the CDC will have to maintain a good situation for three months continuously at least.” He added that inspectors are trained to investigate beyond what the CDC staff shows them.

CDCs are then classified into green, yellow, and red categories based on a score covering 17 themes. In 2023, 239 CDCs were green, 65 were yellow and 2 were red. Mr. Hegoda Arachchi explained that the monitoring process is struggling with a lack of staff. “Many people have gone abroad or switched jobs,” he said, “but we are still completing each year.” Mr. Hegoda Arachchi stated that while the NCPA has the right to monitor CDCs, actually taking punitive action against them is up to the provincial probation departments.

Due to the effects on children’s wellbeing, government policy has been that institutionalisation in a CDC should be avoided as much as possible. Nevertheless, in practice this is not so. The 2024 committee found that efforts had been made to reintegrate only 20% of institutionalised children.

The remainder will likely live out their childhood in CDCs. With a lethargic monitoring system, at best they might suffer from a lack of personal attention and mental health care, and at worst may be abused and in danger, with little hope of anyone noticing.

| Lengthy legal process and traumatic institutional child care system Many children in CDCs are involved in legal battles, due to instances of abuse, neglect, or custodial problems. For children, the legal system can be brutal, and in abuse cases in particular, justice and healing is hard to come by. Court cases related to abuse can take years and even decades, making it difficult for the child to get justice or indeed to move on. As Nevedita Jeevabalan, the Manager of Child Protection at LEADS, says: “There are girls who go into the court as children carrying a doll and come out as adults carrying their baby.” Akila, who was sexually abused as a teenager in 2011 endured a long gruelling battle, with his case only concluding eight years later, well into his adulthood. Akila had the support of his family and LEADS, an NGO working on child protection, but even so it was a painful process. “The opposition lawyer was very intimidating as if he was going to hit me,” said Akila. Legal delays hinder reintegrating children into society, particularly those who have been placed in an institution due to an ongoing abuse trial. In Safe Homes and Remand Homes–special state institutions meant to house child victims and child offenders during trial–“there is no schooling or regular programming”, explained Ms. Jeevabalan adding, “it becomes very difficult to re-enter society as an adult.” Mishaps in the legal system also result in entirely unnecessary institutionalisation. When there is an instance of child abuse the police are expected to inform the probation office within 24 hours and the probation officer should be present at court with the child. But according to Dr. Jayawardena, sometimes police do not inform promptly . “The main danger of bringing the child before the magistrate without a probation officer’s report is that it increases the likelihood of institutionalisation as the magistrate may not know of a suitable relative with whom to place the child, if needed,” he explained. If the magistrate determines that the home is unsafe, and no probation officer is present to suggest an alternative care system, the child will likely be sent to an institution. The lengthy legal process and traumatic institutional child care system is, according to Dr. Jayawardena, a key reason for under-reporting child abuse. Akila did not receive any mental health support from the state in the aftermath of his abuse. In his small village word spread fast and he suffered bullying and isolation. Now working as a pastor Akila says his one aim is to “make sure nobody goes through what I did.” | |

The best way to say that you found the home of your dreams is by finding it on Hitad.lk. We have listings for apartments for sale or rent in Sri Lanka, no matter what locale you're looking for! Whether you live in Colombo, Galle, Kandy, Matara, Jaffna and more - we've got them all!