News

Outdated laws and societal norms fail women enduring marital rape

View(s):By Tharushi Weerasinghe

In Sri Lanka, a woman loses her legal right to consent, or not, once she enters into marriage.

Ms. Samanthi, 34, whose name is changed for privacy, works in a small-scale bag factory in Gothatuwa, has a teenaged daughter, and regularly suffered rape by her husband. But legally, there was nothing she could do about it.

“He would come home drunk at around 2 a.m. every day, 6 a.m. if he goes night racing on his tuk-tuk, and it doesn’t matter if I am sick, tired, or asleep, and I always have bruises all over me the next day because he’s maniacally rough. I hate it.”

Under the Penal Code, rape is only recognised as such if the couple is judicially separated. The law also permits the marital rape of girls as young as 12 years despite the age of consent being 16 years in Sri Lanka. This loophole is one in a long list of discrepancies surrounding the definition of rape in Sri Lanka’s legal system under which the rape of male victims, even male children, for instance, is not recognised.

These assaults fall under the purview of “grave sexual abuse” and carry penalties that are similar to those of rape.

“The non-recognition of marital rape is the failure of the law to recognise all forms of rape completely,” said lawyer Ermiza Tegal, who added that the move by the legislature not to extend the protection of the law to a person simply because the act is committed within a marriage is a “deliberate one’’.

UNFPA Sri Lanka Representative Kunle Adeniyi

This is further exacerbated for children and women married under the Muslim Marriage and Divorce Act, which legitimises child marriage. “The two laws—MMDA and the exception to the rape law in the Penal Code—work together to create conditions in which Muslim children cannot seek any redress if raped within a marriage,” she noted.

Ms. Tegal also said that while abuse or rape are not grounds for divorce in Sri Lanka, it forms part of the story that explains why a woman was compelled to leave the matrimonial home. “Malicious desertion, including constructive malicious desertion (forced to leave by the malicious acts of the other), is one of the three grounds for divorce in Sri Lanka. The other grounds are adultery and impotency.”

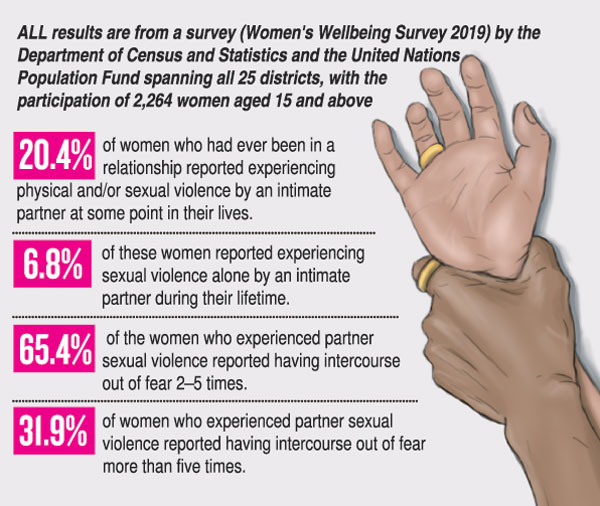

According to the Women’s Wellbeing Survey 2019, by the Department of Census and Statistics and the United Nations Population Fund, one in five women (20.4%) who has ever been in a relationship reported experiencing physical and/or sexual violence by an intimate partner at some point in their lives.

The survey also revealed that 6.8% of women reported experiencing sexual violence alone by an intimate partner during their lifetime. Many of these women mentioned being forced into sex when they did not want to, simply out of fear. Among those who experienced partner sexual violence, 65.4% of women who had intercourse out of fear reported it happening two to five times, and nearly one-third (31.9%) experienced it more than five times.

“What makes these numbers even more concerning is that nearly half (49.3%) of women who endured sexual violence by a partner did not seek any form of formal help,” stated Kunle Adeniyi, country representative of the UNFPA in Sri Lanka. He noted that responses to their survey revealed that the main reasons for not seeking support were deeply rooted in feelings of shame, fear of blame, and, in many cases, a societal perception that such violence is a “normal” part of marriage.

He said that while the data collected provided valuable insights, it was likely a severe under-representation of the problem.

“The data from the Women’s Wellbeing Survey is one of the most representative pictures of the issue so far, but it is essential to recognise that the real situation remains hidden due to the stigma, fear, and social conditioning surrounding it because we observed that many women don’t feel safe or comfortable talking about their experiences, even in an anonymous survey setting.”

Other sources of data, such as police reports, hospital records, or calls to helplines, also fall short of capturing the full extent of the issue, as they only account for cases where women reach out for help, often as a last resort.

“In my humble opinion, Sri Lanka’s laws should be reformed to provide married women with comprehensive protection from sexual violence, ensuring their rights to dignity, autonomy, and health are fully upheld,” said Mr. Adeniyi, who felt that the current legislation’s “narrow provisions” overlook the “harmful presence of sexual violence within marriage’’. This limited legal framework not only places married women at heightened risk of repeated abuse but also perpetuates harmful social norms that view marital consent as irreversible.

Mr. Adeniyi also said criminalisation must extend to marital rape in all circumstances through amendments to Section 363 of the Penal Code and removal of the loopholes allowing marital rape of girls over 12 by standardising the age of consent to ensure equal protection.

“It would empower victims to seek justice, encourage societal shifts toward respecting women’s rights within marriage, and ultimately uphold Sri Lanka’s commitments to international conventions like the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR).”

Both the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) Committee (in 2017) and the Human Rights Committee (in 2014) have recommended that Sri Lanka recognise marital rape as a criminal offence.

The then Justice Minister Wijedasa Rajapaksha had announced that efforts were being taken to criminalise marital rape in March this year; however, the law currently remains as it is.

While legal reforms are an important step, a change in societal thinking patterns remains vital for holistic change.

“To fully address and prevent sexual violence, the legal reforms should be accompanied by widespread access to comprehensive sexuality education (CSE), which teaches young people about respectful relationships, consent, and bodily autonomy, equipping them with the knowledge to recognise and challenge harmful gender norms and stereotypes,” Mr. Adeniyi said.

He said that through CSE, girls and women become more aware of their rights and are empowered to speak out against abuse while playing a crucial role in educating boys and young men about respect and equality, fostering a culture where violence is neither tolerated nor normalised.

The only countries in South Asia that criminalise marital rape are Bhutan and Nepal, but the concept of recognising and criminalising rape within marriage is a fairly new legal protection even in the United Kingdom, where the law was introduced 33 years ago. About 150 countries criminalise the act either explicitly or by not differentiating between the perpetrator being a spouse or anyone else.

Ms. Samanthi has managed to get a divorce and is raising her daughter with the salary she earns by working as a supervisor in the factory.

“I know I was lucky to even have the understanding that what was happening to me was wrong and break away because some women that I shared my story with did not understand how I could be upset with my ex-husband for wanting sex even when I did not,” she says.

She claims that leaving her husband was easier because she had parents who supported her and a job to financially provide for her and her daughter.

“Being able to afford a life independently and knowing my rights to my body set me free, and this needs to be promoted more because too many women I know are okay living a life of abuse simply because they do not know better, but we deserve more than that.”

The best way to say that you found the home of your dreams is by finding it on Hitad.lk. We have listings for apartments for sale or rent in Sri Lanka, no matter what locale you're looking for! Whether you live in Colombo, Galle, Kandy, Matara, Jaffna and more - we've got them all!