News

Memories of that fateful day are still vivid to many

View(s):- Twenty years after the deadly tsunami of December 26, 2004 brought death and destruction to the country, Tharushi Weerasinghe visits the southern coast

“I felt utterly betrayed by the ocean—it gave me palpitations just to look at it, which felt wrong, as though a lifelong friend, integral to my identity, had suddenly turned on me and taken almost everything I had,” says tsunami survivor Shamali Dickumburage.

On Thursday, a week away from the 20th anniversary of the Boxing Day tsunami, that left a trail of death and destruction, the Sunday Times visited the southern coast to speak with survivors.

December 26, 2004: Devastating scenes at the Galle bus stand and right, Peraliya train tragedy, in the aftermath of the tsunami

Twenty years after that devastating day, on December 26, 2004, Shamali says a day that started like any other in Mirissa turned into a ‘run for her and her family’s life’. That fateful morning, Shamali was attending to a tourist at her dispensary when sudden shouts of “run!” and “the sea is flooding!” pierced the air. Stepping outside, she was momentarily frozen by the sight of the waves surging toward the shore. “At first, my legs wouldn’t move, but I managed to reach my family, and we drove to a relative’s house inland,” she says. They spent a week there before returning, fearing what they might find.

Many lives were lost in Mirissa, though it was not as severely impacted as other areas of the country. “People were curious and walked toward the sea, only to be caught by the waves that followed,” Shamali recalled.

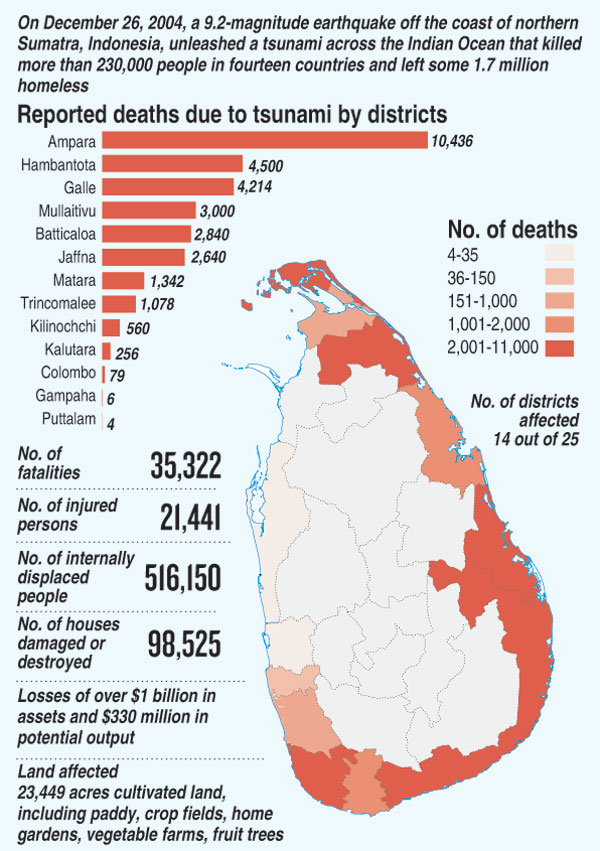

Official figures reveal the staggering impact of the tsunami, triggered by the 21st century’s strongest Asian earthquake. Over 220,000 lives were lost across 15 countries. In Sri Lanka, more than 30,000 people perished, with many still missing, making it the country’s most catastrophic natural disaster. According to the World Bank, it caused over $1 billion in asset losses and $330 million in potential output. The destruction left 35,000 dead or missing, wiped out 70,000 homes, and left 250,000 families without livelihoods.

'Even if a tsuanami doesn't kills us these houses will', say some who pointed to the state of the houses built for them

Two decades later, survivors like Shamali live with the scars of that day, their memories a poignant reminder of the ocean’s power to give and take.

Further, along the coast in Ahangama, 59-year-old Nandani sells coconuts and other refreshments to tourists on the beach. She was a recent widow and mother of three the day the tsunami took her home. “I worked abroad and had returned earlier that month.” She was asleep when the sound of running and screaming jolted her awake. People were rushing through her garden, shouting warnings about the sea coming ashore—a phenomenon she had never heard of before. She stepped onto the road to see for herself. “I thought they were lying, but the water was coming in so fast, I had no choice but to run,” she recalls.

Residents are critical of the state of the tsunami towers and lack of preparedness but officials tell a different story. Pix by Priyanka Samaraweera

In the chaos, she tried to shut the doors of her home but quickly realised there wasn’t time. The air was filled with screams and cries of despair. “I heard people shouting, ‘My father is gone, my daughter is gone,’” she says, the memory still vivid. She and her family sought refuge at Uganwala temple for three weeks before returning home to assess the damage. She found a dog’s body in her living room, and the few valuables she owned were robbed, she says.

Shamali Dickumburage

While recovery efforts included rebuilding homes for those affected, many survivors, like Nandani, were left disappointed. “The new houses weren’t up to standard,” she explains. “I told them, last time we were saved because we ran from the tsunami. Now, if one comes, we’ll die from the house falling on us.”

At the China friendship tsunami village in Kurunduwatta, Galle, houses are derelict, and some have been abandoned. “We got this house after we lost our home. I ran with my in-laws and children. My husband was at work,” said Kumudini Vidanage, a 55-year-old resident. The house they were given began falling apart a year after moving in. “We are not people who should be living in this state, and we had to build from scratch because our leaders at the time stole from us.” She claims that they were one of the few lucky families who could afford to renovate the house they received, but many of her neighbours were making do as best as they could despite parts like windows rotting and falling off.

B. Suneetha

“My wife and daughter managed to get to an upstairs building somehow, but I was on the ground floor when the water started filling in,” says H. P. Padmakumara, a 53-year-old residing in one of the inroads near the Galle bus stand. He recalls feeling like he was stepping on fish as he tried to wade through the water to safety. Later he realised he was walking on bodies.

B. Suneetha, a 63-year-old who now has a peanut stall at the stand, used to sell fruits there back in 2004. “The policeman who was at the bus stand asked me to ‘run”. I asked why, and the water hit,” she said. She ran up the stairs to the next floor of the bus stand, but the walls around her caved in. She says her most horrific memories are of children she saw being washed away or falling into the water. Official records show that 40% of Sri Lanka’s deaths caused by the tsunami were children.

H. P. Padmakumara

Many survivors claim that tsunami awareness and evacuation drills have largely ceased since 2007. “Our children know where to run because we teach them, but there has been no effort from government officials,” says 43-year-old fisherman Ajith Nishantha at the Galle fish market. He says that while fishermen receive SMS updates on wind patterns and weather warnings, tsunami discussions are limited to December 26 every year, when families gather at the Kurunduwatte cemetery to remember loved ones. Mr. Nishantha, who was home during the tsunami, says he was disappointed with the government’s response, noting that NGOs replaced his boats only in 2006. He is also critical of the tsunami alarms, claiming they are rung only on anniversaries for commemoration, not for evacuation drills.

Some residents and survivors claim that the tsunami warning towers do not work at all. “We set up 11 towers on our own with help from foreign donors right after it happened,” said Roshan Waduthanthri, a 53-year-old, the coordinator of the community tsunami education centre in Peraliya, Hikkaduwa. He had moved into his newly built house four days before the tsunami struck in 2004 and was a volleyball player for the Sri Lankan Army at the time.

Ajith Nishantha

“We were using these towers for awareness announcements until the government introduced their towers in 2009, and the Disaster Management Centre told us that the legal authority lay with them and not us, so we stopped and started to share ‘weather information” with the local fishermen instead. But these towers put up by the govt. have not worked in at least two years, he said. At present the centre functions as an information sharer and regularly hosts school students.

Mr. Waduthanthri also maintains a 24-hour earthquake monitoring system with Bluetooth attached to an alarm that goes off in his home when necessary. The Centre also maintains five “focal points” in the area that are gathering points for villagers in case of an emergency and has 2 bikes with megaphones that are ready to go around making announcements when necessary.

Roshan Waduthanthri,

He was critical of government response to their complaints about the tsunami towers being broken. “We were told that other systems like SMS alerts exist, but this is not a practical solution for areas with low-income households that have elderly people in them,” he said.

Peraliya marks the location of the world’s single largest rail disaster, the “Queen of the Sea” train tsunami crash, which claimed over 1000 lives. Tsunami photo museums, community education centres, and memorials like the tsunami Honganj Viharaya and the Peraliya tsunami memorial stand as a remembrance of that fateful day.

One of the museum managers, 68-year-old Lal Wickramaratne, was a fisherman when the tsunami hit. “I don’t go out to sea on poya days, so I was home.” He told the Sunday Times that he started the museum in 2018 to raise funds for various children’s organisations because of the heartbreak in memory of his nephew and niece, who were snatched away by the waves that day. “They came to our house every Sunday—but not that day. Their dad was at sea, and their mother was at the market. If they had come as usual, I’d still have them. Losing them was unbearable.”

Photos of these children take centre stage at the museum, along with the only thing he took with him as he ran for his life that day—a blue sarong with his writing on it. “My head was spinning because I could not understand what happened or comprehend that the children were gone,” he said. He spent a lot of time collecting photos from various people, buying them, to build the museum.

“It is unforgivable that the government cannot even maintain a tsunami warning tower after everything we lost that day,” he said, claiming that the SMS alert system was completely inadequate as protection. “What happens if a disaster strikes at night when everyone is asleep? How is an SMS supposed to wake me up? How do they expect people without a phone to know?” he questioned. Mr. Wickramaratne claimed that out of the 77 towers that were constructed across the country, over 50 do not work.

Some of the remembrance monuments that dot the southern coast

Records from the National Audit Office corroborate his statement. Out of 77 disaster warning towers installed in 2016 by a private company for the Disaster Management Centre (DMC) at a cost of Rs.134.7 million, 55 have become nonfunctional. The project also failed to update the multi-hazard risk index variations needed to create a comprehensive risk profile.

“We have begun procurement procedures to repair and upgrade our towers,” noted Pradeep Kodipilli, director and media spokesperson for the DMC. These renovations are being done with support from a World Bank project called the Climate Resilience Multi-Phase Programmatic Approach (CResMPA). He added, however, that towers are one of 14 ways in which early warning is handled in Sri Lanka and were not working because they were 15 years old now. He claims the upgrades, which are set to be completed by the end of 2026, include the introduction of innovative practices and state-of-the-art systems that will enhance the 117 emergency services and disaster management centres across all the districts in the country.

He also vehemently denied allegations that awareness programmes were not being conducted. “Just this year the DMC alone conducted about 300 awareness programmes and an additional 150 were done with private sector/NGO support.” He stated that awareness programmes were implemented across all 14 tsunami-vulnerable districts and communities, accompanied by evacuation drills. He noted that training sessions were mostly attended by women, as men were often at work, but added that women did not relay the information back home. He did not explain how the DMC came to this conclusion.

“We are conducting training programmes for 1500 youth volunteers with the National Youth Services Council and regularly train youth corps in every district.” He also added that development officers from the divisional secretariats were also given regular training and that tsunami evacuation boards were up at necessary places.

The Sunday Times, however, did not observe any boards by the DMC during our field investigation on Thursday. Mr. Kodipilli then said that some have been defaced due to land price issues raised by owners. Apart from this, he said schools in Galle, Matara, and Hambantota affected by the tsunami now have disaster committees, evacuation plans, and guidebooks on disasters in Tamil and Sinhala, incorporated into the curriculum.

State and government employees, health sector networks, and local communities have received disaster management training, with approximately 500 sessions held annually, often in partnership with organisations like the Red Cross and Sarvodaya. Triforces and police officers are trained regularly and then dispatched nationwide.

The hotel sector has also undergone staff training, including evacuation plans. SMS alerts for disaster warnings are provided free of charge, though complaints about their effectiveness persist.

“It is very surprising to me that anyone would claim these things are not happening, but we will keep conducting these trainings with or without funds, and we are always open to the public’s feedback on gaps that exist so that we can fill them,” he noted.

The first authorities to monitor, inform, and safeguard communities from natural disasters like tsunamis are the DMC and the Meteorological Department. “We currently depend on three regional centres located in India, Australia, and Indonesia that monitor earthquakes and measure the tsunami risks of each event,” said Srimal Herath, duty forecaster at the Meteorological Department. Based on severity and relevance, the department then communicates the event as “information” or an “advisory/warning” if a serious threat arises. “We have an alarm system that alerts us to earthquakes with a magnitude of 5 or higher, but we only take action after receiving confirmation from the regional centres.”

The best way to say that you found the home of your dreams is by finding it on Hitad.lk. We have listings for apartments for sale or rent in Sri Lanka, no matter what locale you're looking for! Whether you live in Colombo, Galle, Kandy, Matara, Jaffna and more - we've got them all!