News

20 years on new threats loom over tsunami-hit coastal areas

View(s):By Tharushi Weerasinghe

Twenty years after the Boxing Day tsunami, Sri Lanka’s coastal areas are still healing from the waves that came crashing in on December 26, 2004. While communities have been rebuilding lives and livelihoods, a new threat looms with coastal vegetation, natural barriers against disasters like tsunamis, becoming casualties of urbanisation.

“When the tsunami hit, I felt that our area was comparatively safer because of the vattakeiya (screw pine) that lined the shore,” one survivor from Mirissa told the Sunday Times. She noted that the shoreline has changed significantly with development encroaching on the beaches as tourism developed in the area.

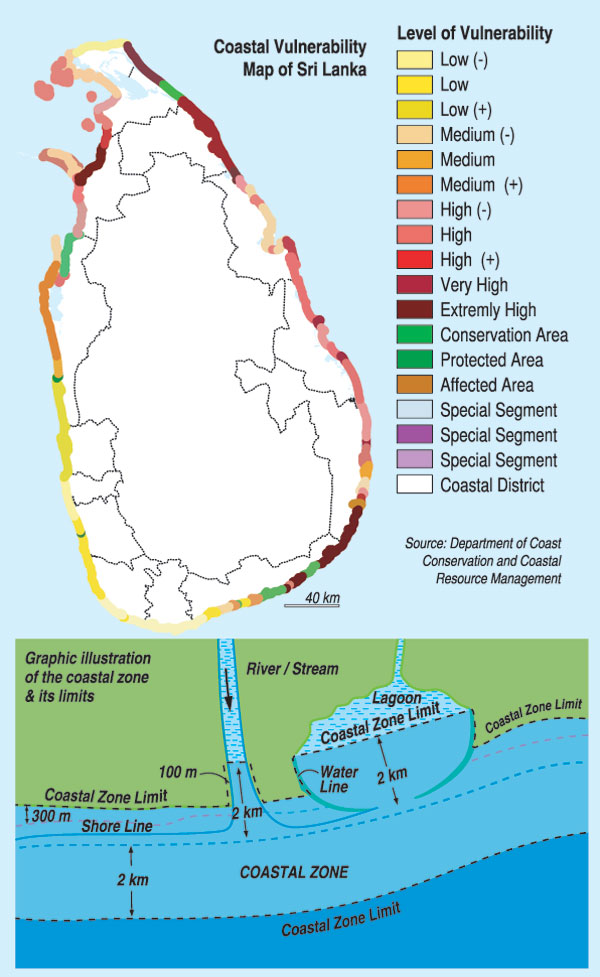

According to the Coastal Conservation and Coastal Resource Management Department’s (CCD) recent coastal zone and resource management plan, the impact of the tsunami on the coastal zone was most severe where there had been some degree of human-induced environmental damage, such as the removal of sand dunes, coral reefs, and coastal vegetation. The report, released in September this year, recognises mangroves, salt marshes, dunes, beach barriers, lagoons and estuaries, other water bodies, and sea grass as the island’s primary coastal ecosystems.

Between shrimp farms, sand and coral mining, and urbanisation, Sri Lanka’s coastal resources have been crippled. Coral reefs, for example, have deteriorated by 90%, mostly due to pollution, according to the Marine Environment Protection Agency. Over the past 30 years, more than half of Sri Lanka’s mangrove populations have reduced.

“Vegetation buffers are important not just for disasters like tsunamis but also for storms and even the sea breeze when it is too strong,” said Eng. Sujeewa Ranawaka, Director General of the Coastal Conservation and Coastal Resources Management Department.

However, he cautioned that these buffers alone are not enough. “This won’t be the one thing that stops a tsunami, especially because the required buffer does not exist in all exposed areas.”

Discussing the specific benefits of vegetation, Mr. Ranawaka noted, “While large shrub plants like vattakeiya do disrupt the force of the wave, the strength of a tsunami cannot be completely tamed by it.”

He noted that sand dunes play a more significant role in protecting coastal areas. “They offer good protection, especially in places like Hambantota and Puttalam and the North-West and East,” he said adding that dunes gave a lot of protection during the 2004 tsunami.

The department has taken measures to preserve these natural features. “We do not approve any constructions on top of dunes and declare them as protected sites in some places, like Panama and Pottuvil. We have also suggested other locations like Ulla be gazetted this way,” Mr. Ranawaka stated. These protected areas remain accessible to the public but cannot be claimed for private ownership.

Encroachment continues to be challenging, prompting the declaration of numerous sites as protected zones. “We have a lot of encroaching issues, which is why we declare so many sites to protect them,” he added.

In addition to vegetation and dunes, the coastal zone is managed under a structured framework. “The 1,620 km coastline has been divided into 95 sections. With this reservation in mind, we give protection,” Mr. Ranawaka explained. Despite these protections, unauthorised constructions persist. “We treat them as unauthorised constructions and are legally empowered through the Act to break and remove them following the legal process, which includes a demolition order and notification period during which the owner must remove their illegal construction or we will.”

The tsunami-affected region face a delicate balancing act, in the region hit by the 2004 tsunami where development often comes at the cost of inevitable ecosystem destruction. “We are losing a lot of vegetation to urbanisation as populations along with their needs for land and resources increase,” said Dr. Mizna Mohamed, Director of Science and Innovation at the Small Island Geographic Society, Maldives.

She held that increased vulnerability in areas without coastal vegetation was also observed by communities in the Maldives. “We have a special name for the coastal vegetation around an island—heylhi—which protects the islands from strong waves, swells, and surges.” She also noted that even under normal circumstances, they play an important role in reducing coastal erosion. “The importance became clear in the 80s when people used coral and sand for housing, but some communities recognised the impact on beaches and created local rules to stop mining, followed by government regulations against it.”

In Sri Lanka, a lack of data and concurrence between government institutions continues to drive the lack of importance given to the conservation of coastal vegetation. Lack of resources to implement the protections that are already in place is also an issue.

Officials in preparedness and mitigation-related institutions believe that coastal vegetation as a “nature-based solution,” like sand dunes and mangroves, should be prioritised more. “With the 2004 tsunami we had an opportunity to learn and develop our coastal zone methodologically, but sadly we missed it,” claims DMC Director of Mitigation and Research Anoja Seneviratne. She noted that structural tsunami mitigation measures were not feasible in Sri Lanka and that Sri Lanka’s experiential knowledge of how damage occurred should be utilised in its planning.

She claimed, however, that at times, decisions that prioritised solutions like these would be shut down due to public dissent because of the impact it would have on the development goals of various industries. “Sometimes we have to let go of the idea of making popular decisions and just make the right decision,” she held.

She added that state institutions had worked to increase coastal resilience despite these pressures. “After the tsunami, we collaborated with the CCD and the Ministry of Environment’s EIA division on how to implement tsunami-resilient construction,” she said, referring to the introduction of tsunami-conscious architecture along the coast with guidance from relevant experts. Hotels along the coast are intentionally designed with no rooms below the third floor, incorporating large open-ground spaces to mitigate tsunami risks. These features are part of tsunami-resistant structural designs developed between 2008 and 2010 through collaboration between the Structural Engineering Association, the Universities of Moratuwa and Peradeniya, the Building Department, NHA, CCD, and DMC. Local governments are responsible for implementing and enforcing these guidelines.

The best way to say that you found the home of your dreams is by finding it on Hitad.lk. We have listings for apartments for sale or rent in Sri Lanka, no matter what locale you're looking for! Whether you live in Colombo, Galle, Kandy, Matara, Jaffna and more - we've got them all!