Loris and the evolution of environmentalism in Sri Lanka

There’s no gainsaying the fact that the Wildlife & Nature Protection Society (WNPS) is, by far, Sri Lanka’s premier conservation NGO. It has for the past 130 years flown the flag for conservation in this country. And during that time, it has not just changed with the times but caused the times to change.

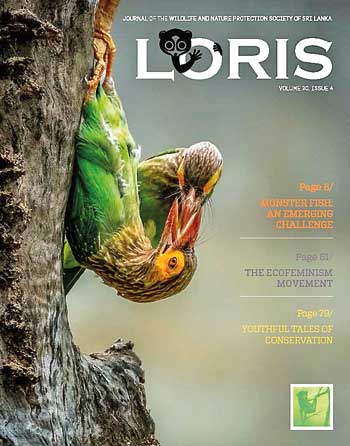

Loris cover page image by Rajeev Amerasekera

Its 3000 members would squirm to be reminded that the Society’s founding ethos revolved around the preservation of wildlife for sport hunting. White men, who were for the most part its founders, needed a steady supply of game to shoot. The aversion to killing wild animals, whether for sport or because they are agricultural pests, occurred only in the lifetimes of many who are alive today. Sport hunting remained a middle-class pastime well into the 1960s, fizzling out in the following decades partly because of changing values but mostly because of gun controls introduced in the wake of the JVP insurrection of 1971.

As recently as 1963, P.E.P. Deraniyagala, by far the most celebrated naturalist Sri Lanka has produced, wrote how when fishing on the Walawe River at Timbirigasmankada (now Thimbiriyamankada), he simply shot a bear and used bits of its flesh as bait.

When ‘Loris’, the Society’s journal, began publishing in 1936 then, hunting was very much ‘a thing’. Indeed, WNPS’s then name was the Ceylon Game and Fauna Protection Society. From the very outset, however, ‘Loris’ never advocated hunting. Instead, it stridently opposed the commercial exploitation of wildlife. This was made clear in 1937 in the very first review of the journal in ‘Nature’, the world’s premier scientific magazine:

“The slaughter of sambar and deer for the sake of the export of their hides and horns had reached gigantic proportions and entailed great cruelty, before the Government in 1891 passed ordinances to check the trade and to ‘prevent the wanton destruction of elephants, buffaloes and other game’. Even so the trade continued, and several subsequent enactments have been required to bring about the protection which was desired.”

But rather than acting merely as a strident voice of opposition to wanton exploitation, the Society thought better results might be obtained by moulding public attitudes through the celebration of nature. “The editors are aware,” continued Nature, “that the stimulation of interest in animal life is a better means to their end than mere denunciation. Accordingly, they include sporting articles of a naturalist flavour, accounts of trips in the jungle, and an instructive article on natural history photography and the apparatus it demands, illustrated by excellent photographs of birds and nests.”

It worked.

The selection of the loris after which to name the journal is striking especially because the animal was of no interest to hunters. It signalled the appreciation of wildlife for its own sake, rather than its utility. I imagine there was heated debate amongst the Society’s committee at the time, about the selection of an unfamiliar diminutive, secretive, nocturnal animal after which to name its journal. There must have been those who argued for something more charismatic: an elephant or a leopard, perhaps. But the name and the painting of a Loris in the moonlight by William Henry Jan Cooke was chosen and remained on every cover for the next 66 years, until it was finally defenestrated by a philistine editor in 1999. It now persists on the cover of every issue of ‘Loris’ only as a stamp-sized vestige of its former self.

The journal has now been issued for 88 consecutive years, possibly the only periodical in Sri Lanka to have done so. Many older journals, not least the National Museum’s ‘Spolia Zeylanica’, fizzled out in the course of Sri Lanka’s post-Independence decline.

WNPS has just released volume 30, number 4 of ‘Loris’, now edited by Sriyan de Silva Wijeyeratne. Keeping with the times, it is issued both in print and electronically, as an open-access PDF. Refreshingly, alongside Loris, WNPS too, has evolved. Most importantly to my mind, the Society has embarked on an ambitious plan finally to give meaning to article 3(e) of Act No. 29 of 1968, by which it was incorporated, “To establish, administer and hold private wildlife sanctuaries and nature reserves”. It is the only institution in the country to be so empowered.

Through a series of innovative public-private partnerships, WNPS’s PLANT initiative has come to manage hundreds of acres of non-state forest land, seeking to conserve in addition to restore native forest on vast extents of deforested land. It is without doubt the most ambitious and important conservation initiative that has seen fruition in my lifetime. Clearly, the donors who are chipping in million of rupees to make this happen agree.

It was WNPS too, that took the lead in litigating against the infamous Adani wind power project in Mannar, thus stymying Ranil Wickremesinghe’s plan to not only to harm the peninsula’s unique wetlands, which facilitate the ingress and egress of millions of birds from Sri Lanka, but also to fleece consumers by charging a tariff 70 percent higher than market rates.

‘Loris’ encapsulates the WNPS’s prevailing ethos, centred on sound environmental stewardship. consistent with that objective, the current issue highlights the risks of ‘monster’ alien fishes and no-less-destructive bladder snails being released into our aquatic ecosystems; the wondrous gathering of elephants at Minneriya; the causes of the dugong’s near extirpation; the crocodiles inhabiting the Kimbulawela tank (right beside my house); biodiversity conservation and restoration by the PLANT initiative; ‘ecofeminism’; conservation insights from India by Valmik Tharpar; a thoughtful essay on earth jurisprudence by Professor Nimal Gunatilleke; and much more.

Once the enemy of industry, WNPS, as its list of donors, sponsors and advertisers shows, now works closely with the corporate sector. While retaining its commitment to radical activism in defence of the environment, the Society has quietly ditched the radical ideologies that bedevilled its mission in decades past. “The people are taking back control of their nation”, it editorialises, but “time is not on our side.”

Thanks to governmental corruption and inefficiency, the environment is worse now than it was when I first ventured into biodiversity research 35 years ago. But there is now a grassroots concern for nature and the environment that was completely absent back then. Rural schools didn’t have nature clubs then. The transformation has been revolutionary. Today, not just NGOs but civil society, the corporate sector and, most importantly, the judiciary choose to defend the environment. The WNPS and Loris, have been front and centre of that transformation. And it is why I remain optimistic that we are turning the corner and will, in fact, hand this country to our children in a better state than we found it.

Searching for an ideal partner? Find your soul mate on Hitad.lk, Sri Lanka's favourite marriage proposals page. With Hitad.lk matrimonial advertisements you have access to thousands of ads from potential suitors who are looking for someone just like you.