Poetry from the hills

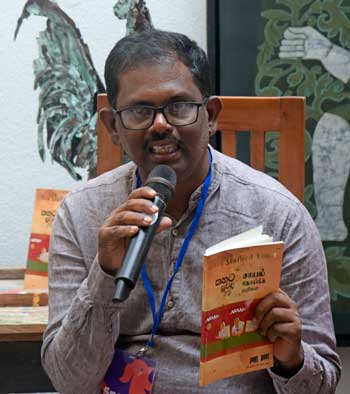

Mylvaganam Thilakarajah at the Tea and Poetry session and below with panelists Jeyakantha Janu and Annal Glory

For Malaiyaha Tamil poetry, context – not imagination – is everything. Mylvaganam Thilakarajah’s office is a testament to this. Surrounded by books on the history and literature of the hill country and framed by photos of famous Tamil literary and political figures, the 50-year-old speaks about his poetry that was this week highlighted at the Galle Literary Festival.

“That photo is of C. V. Velupillai,” he says pointing to a black and white photo on his shelf. Velupillai was born on the same estate in the Nuwara Eliya district as Thilakarajah. They attended the same school, moved to Colombo for higher studies, and entered politics. Both were also poets. “Even without my knowledge I was attracting his life,” chuckles Thilakarajah, who writes under the name “Malliyappusanthi Thilakar”.

Thilakarajah first started writing poetry in school. He encountered Velupillai’s work in his Tamil literature syllabus and describes it as having a “big impact” on him to have learnt, in that moment, that such a famous poet was from his town.

Velupillai originally wrote about big topics like Indian independence or very imaginative, romantic poetry, explained Thilakarajah. But then he received a letter from a fellow poet imploring him to “look around at your own people”. Thilakarajah says that since Velupillai was from a supervisor family in the estates it was only then that he turned and noticed the workers he lived among and encountered a rich folk culture. It was collecting these folk songs, and the writings inspired by them that shot Velupillai to fame.

So too, says Thilakarajah, Malaiyaha poetry is always heavily steeped in its context. He flips open an anthology published by PEN Sri Lanka featuring 20 poets. All will have their “personal ingredients” of course, he says, but the base is not from imagination but rather from context: from the geography of “mountains and valleys”, from the language of “coolie Tamil” that then became “Malaiyaha Tamil”, and from the depth of faith in their gods.

Thilakarajah rolls verses off his tongue to prove his point. They tell of determination to make Sri Lankan their home, even as Malaiyaha Tamils were disenfranchised by the government in 1947. Another verse laments the painful servitude to colonial masters. Folk songs, Thilakarajah believes, act as an archive of the community’s history. And even modern Malaiyaha poetry, he says, contains this habit for story-telling and is inspired by folk traditions. “It is our cultural inheritance.”

Reading Thilakarajah’s poems it is not hard to see his point. They have a steady almost chant-like rhythm and repetition not unlike a short song made and repeated over and over with the intention of being passed on in the absence of a written record. With religious and political motifs, his poems speak of the suffering, faith and betrayal of Malaiyaha people.

“One of my poems emerged from witnessing a trade union demonstration at a junction,” Thilakarajah explained. “My poem was a way of writing that story. The context transforms into poetry.” In a literary tradition so steeped in context, such explicitly political poetry becomes inevitable. Indeed, not only has political turmoil influenced art but art too has had a major role to play in Malaiyaha Tamil politics.

Although no longer as heavily involved in politics, Thilakarajah openly shares his concerns about the political and social transformations affecting his community and their cultural identity. “To put it simply, our culture historically is South Indian but it is becoming North Indian,” he says of increasing modern Indian influence in the hill country.

He worries about the loss of language in southern estates in Kalutara and Galle as communities switch out of necessity to Sinhala. He ponders the loss of geographic identity as youth move from the mountains to the cities, involving their minds in new issues and struggles. “I am not saying it is good or bad, but the dimension of our community is changing, and I do see that in some way as a threat to our identity,” he sighs.

The long tradition of Malaiyaha Tamil literature from folk songs through poems, novels, short stories and plays must be uplifted, says Thilakarajah. While nationally and internationally people see and speak about the economic hardships of his community, little attention is given to their rich literary tradition. “This side of our community should be developed too.”

Searching for an ideal partner? Find your soul mate on Hitad.lk, Sri Lanka's favourite marriage proposals page. With Hitad.lk matrimonial advertisements you have access to thousands of ads from potential suitors who are looking for someone just like you.