Sunday Times 2

Whither Sri Lanka’s paddy farmer?

View(s):By Dr. Parakrama Waidyanatha

During the reign of King Rajasinghe II, the English sailor Robert Knox, in his book titled “An Historical Relation of the Island Ceylon,” describes the social status and lifestyle of people. An oft-quoted statement from the book is, “Once the mud is washed off the paddy farmer, he is fit enough even to be the king!” What was not said is that the paddy farmer was then too poor, as he is now.

Farmer education is vital for an agriculture boom

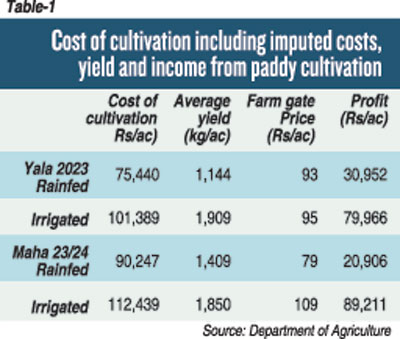

Whilst we have made commendable achievements in breeding high-yielding paddy varieties and other technologies leading to rice self-sufficiency/food security, the paddy farmer’s income has not been given due consideration. Table 1 is based on the latest published data of the Department of Agriculture. It depicts the poor returns to paddy farming across the country.

An acre of paddy during both Yala and Maha seasons (whole year) with imputed (family labour, tools and machinery) costs gives a return of about Rs 169,000 and 52,000 per year under irrigated and rainfed conditions, respectively. The government’s decision to declare minimum farmgate prices of Rs 120, 125, and 132 a kilo, respectively, for the three key paddy varieties, ‘Nadu,’ ‘Samba,’ and ‘Keerisamba,’ should increase the farmer returns by 20 to 30%. However, the farmers are clamouring for Rs 130 a kilo and more!

Most farmers make a living with additional income from off-farm employment, and farm income studies have shown that 60% or more of the farmer’s income is from such employment. Large tracts of irrigated paddy lands in areas such as Ampare are leased to entrepreneurs (mudalalies), and some farmers earn a wage providing labour in those farms.

Apart from the poor income from paddy farming, the massive water requirement for it, as it is practised now, is a serious concern. As much as 3000 to 5000 litres of water are required to produce a kilogram of rice in the manner it is usually done, and as much as 50% and 20% of water is wasted during Maha and Yala seasons, respectively.

Further, research has shown that crop establishment at the beginning of rain, and instead of keeping the field submerged throughout crop growth but maintaining the soil at the maximum wet condition (field capacity) by alternate wetting and drying, can reduce 70% of the water use without affecting the paddy crop yield.

Such water conservation can preserve the water for optimum cultivation of more income-generating crops in the Yala season, especially in the dry and intermediate zones. Agricultural authorities should move in this matter resolutely not only to increase farmer income but also to increase the production of subsidiary food crops, much of which are now imported.

At present only about 70% of the cultivable extent of the well-drained soils is cropped with subsidiary crops in the Yala season, largely due to water shortage, and preserving water as said above and by other means should enable optimum subsidiary crop production in the Yala.

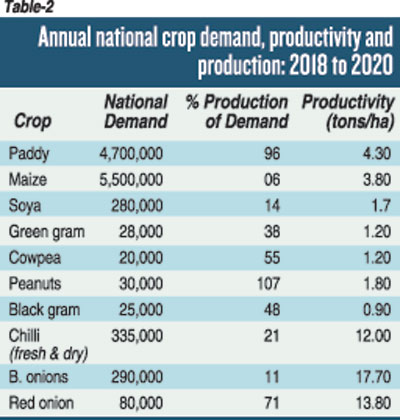

Table 2 gives the local demand, the percentage of the production of the demand and the productivity of arable crops.

Whilst the production of paddy could meet the country’s rice demand in most years, with the new varieties that are now emerging, such as AT 362 and Bg 374, with potential research yields approaching 10 tonnes/ha, with improved crop management, it should be possible to increase our national yields, thereby reducing the cropping extent. It will also enable the diversification of part of the land, especially cultivated with rice in the Yala season in the dry and intermediate zones, to subsidiary crops. However, the yields of many of our subsidiary crops are low compared to what is achieved in other tropical countries, and the attention of the authorities in that matter is one of high priority.

Table 3 establishes the potential for increasing farm incomes by proper crop diversification and intensification.

During the midseason in the dry and intermediate zones, cropping is essential in this regard. From an annual income of about Rs. 250,000 per acre from paddy cultivation during both Yala and Maha seasons, appropriate cropping in the midseason and diversifying into crops other than paddy in the Yala can generate an income of more than Rs. 2.5 million/ac with appropriate crop selection. This is the answer to poor returns from paddy for the dry and intermediate zone farmers.

For the wet zone farmers, too, the answer is in the diversification of paddy lands. The paddy yields in the wet zone are generally much lower than those of dry and intermediate zones. For example, for the Yala 2023 and Maha 2023/24 seasons, according to DoA data, with imputed costs, the Kandy district suffered losses of Rs 26,442 and 44,388/ac as returns. The Kalutara District had a profit of only Rs 24,386 but a loss of Rs 26,422, respectively, for the two seasons. Poor returns have led to abandoning as much as 140,000 acres of paddyland, mostly in the wet zone.

These and other low-yielding paddy lands can be diversified after proper draining and preparation of raised beds as done under the Sojan system in Indonesia. Coconut, oil palm, and other crops can be cultivated, giving much higher income to farmers.

If about 115,000 acres can be cultivated with oil palm, the country’s total palm oil demand could be met; and already many small farmers have expressed willingness to do so.

In conclusion, there is no argument that we should produce our own rice from the point of food security, but it can be done with a much smaller land extent with modern high-yielding cultivars and proper use of other inputs.

There are already reports of farmers in Hambantota and other places achieving double the national yield with the new varieties. Concurrently, crop intensification and diversification with other subsidiary crops, as discussed in this article, could substantially increase farm incomes, producing also the country’s needs of subsidiary food crops.

However, despite these possibilities, most paddy farmers prefer the easy way out by sticking to paddy cultivation during both seasons because the paddy crop needs much less attention than other crops! This farmers’ mentality should change! Concurrently, to bring about all these changes, the highly deteriorated extension service, following its provincialisation, should be uplifted. The new government should address this issue as a matter of highest priority.