News

From Indian-Origin Tamils to Malayagam: New identity embroiled in divisive debates

View(s):By S. Rubathesen

It took nearly two centuries for a community of workers, brought into the country then known as Ceylon from India by the British Raj, to toil in plantations under treacherous conditions in the upcountry region, to assert their own new identity—the Malayaga Tamils—together with socio-economic and political rights for a dignified life.

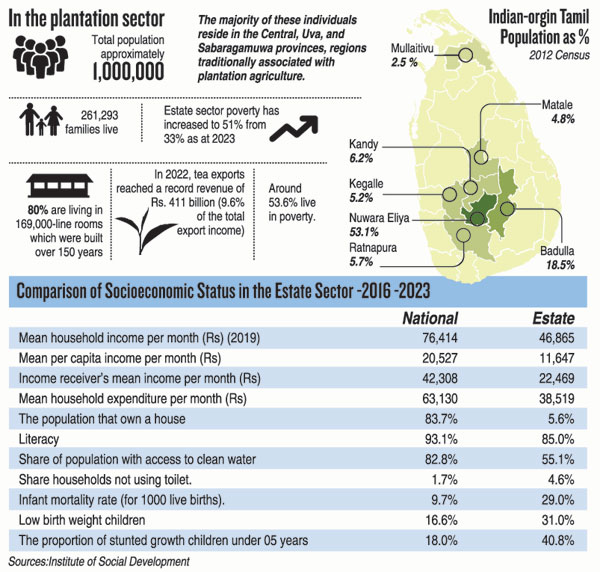

The term Malayagam denotes the mountainous upcountry region where nearly one million people from 261,293 families still reside, most of them in 169,000 line rooms. These ramshackle houses were built more than 150 years ago and continue to be in use with minor modifications to this day.

The term Malayagam was initially coined by civil society groups, political pressure groups, and intellectuals from the community commonly known as ‘Indian Origin Tamils’ to bring them under an umbrella with a new definition. The new identity was promoted as deliverance from the generations-long discriminatory practices the community was subjected to in the past.

When President Anura Kumara Dissanayake presented his Budget-2025 on February 17, he had a specific allocation under the title “Programmes to Uplift the Living Standards of Malayagam Tamil People”. This was the first time that a Sri Lankan head of state recognised the community with its new identity. As finance minister, he allocated Rs 7.5 billion (7,583 million) for various development programmes to improve the living conditions of the community.

In his budget speech, the President said, “The Malayagam people are a part of the Sri Lankan nation and have been living with significant difficulties over a long period of time. However, the livelihoods of this community still remain below standards to have a dignified life.”

The budget allocation is to be distributed for the development of estate housing and infrastructure development, vocational training, livelihood development of Malayagam Tamil youth, and smart classrooms for schools in the Malayagam Tamil community.

The President also stressed that the daily wage of some 1.5 million plantation workers needs to be increased up to Rs 1,700—a key demand was put out by trade unions affiliated to his party, the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna, and the ruling National Peoples’ Power alliance on May Day rallies last year.

Currently, estate workers are paid a daily wage of Rs 1,350 and a daily special allowance of Rs 350, along with an additional fixed Rs 80 payment for every kilogram of tea leaves they pluck.

Welcoming the presidential recognition, P. Muthulingam, executive director of the Institute of Social Development (ISD), a Kandy-based civil society group that campaigned and advocated for the new identity, said, “Finally the community has been recognised under this new label as a distinctive ethnic identity overcoming generational challenges it witnessed in the past.”

The discussion on the collective term for the community became a hot political talking point among plantation political parties when a 2023 circular issued by the Registrar General’s Department required Indian Origin Tamils to register as “Sri Lankan Tamils”.

The pushback led to the withdrawal of the circular, allowing the community to self-identify them as they wanted them to be called. Later, the department also agreed in principle that the term “Malayaga Tamils” can be used when declaring the ethnicity in official documents, but the decision is yet to be implemented pending legal issues.

The recent population census also sparked fresh discussions among the community on how it wants to be identified, as many actors claimed that there was misidentification where many Indian-Origin Tamils were mistakenly considered Sri Lankan Tamils.

When Mr. Muthulingam wanted to register the birth of his granddaughter, he came to know that the new label is yet to be given legal effect to put on official documents.

Later, his organisation, ISD, handed in a set of policy recommendations on January 30 to Prime Minister Harini Amarasuriya seeking a declaration of the Malayaga Tamils community by name and the issuance of a Gazette notification to enable those who wish to identify as Malayaga Tamils to do so in all official records, including birth, marriage, and death certificates.

The ruling NPP swept both the presidential and parliamentary elections, securing a significant vote block from the plantation community. A significant move in wooing the community was the NPP’s Hatton Declaration on October 15, 2023, under the theme of “200 years of history, culture, and struggle—‘Power for the Motherland—A Dignified Citizen.’ It declared that “We (the NPP) recognise and respect the identity of the Malayaga Tamils as an integral part of our nation’s diverse fabric.”

Despite the resilience of the community for generations as a workforce in the tea and rubber industry, around 53.6 percent of them remain in poverty, according to a World Bank report.

The new collective assertion of the community also reiterated its right to own a piece of land and be able to live in a decent house, which still remained a ‘dream’ for thousands of plantation people still languishing in line rooms with limited basic facilities.

Mylvaganam Thilakarajah, a former parliamentarian from the Nuwara Eliya district, told the Sunday Times that his community’s new cultural identity should be protected and preserved just like that of other Tamil-speaking communities in the country. But he said he would suggest a slight variation for better assimilation for his community to be known as ‘Sri Lankan Malayaga Tamils’.

“The Indian label attached to us diminished our identity as ‘Sri Lankans’ in the past. First, we have to gain the identity of Sri Lankan,” the former MP said.

Mr. Thilakarajah questioned what the community had achieved in the past 200 years by retaining the ‘Indian’ tag and asked how long the community should wait to attain betterment if it were to maintain that identity.

Though the community settled mainly in the country’s highlands, working on plantation estates originally, they were also subjected to external factors such as political oppression and ethnic riots in 1958, 1977 and 1983, forcing them to be displaced to other parts of the country. About 70,000 of them live in the Kilinochchi district. Most of them were provided state land plots under successive governments to build houses.

Despite the new identity, the debate on how they want to be called is still alive amid diverse viewpoints based on geographical locations and social and political aspirations—particularly those who migrated to urban cities seeking employment or educational purposes.

Those who moved to Colombo and other western and southern areas seeking employment and have been settled there for decades prefer the wider identity “Sri Lankan Tamils,” just like Tamils in the Northern and Eastern provinces are classified.

A Kilinochchi-based writer and social justice activist, A. Karunakaran, points out social discrimination faced by the Malayaga/Indian-origin Tamils in Kilinochchi.

“Even though this community settled in Kilinochchi mainly, they were not welcomed by the Northerners, nor did the Tamil political leadership include them in their cause. They were discriminated against in social and political spheres. They remain alienated in the region where caste and class play a major role in social settings,” he said.

Today, the Malayaga community in Kilinochchi is still struggling to place itself, and most of them prefer to let go of the ‘Indian Origin Tamils’ tag and be known as “Sri Lankan Tamils”.

“The Tamil society as a whole let them (the Malayaga/Indian-Origin Tamils) down despite the community staying put to the Tamil cause and even subjected to forced conscription of their youths to militant groups till the final battle in the Mullivaikaal. With the last two generations becoming more educated and many of them in state service, they would prefer to integrate and identify as fellow Sri Lankan Tamils rather than Indian tags, hoping their future generations will not have to go through the difficult past they witnessed,” writer Karunakaran stressed.

A glimpse of the socio-political tensions centring on the Malayaga or Indian-Origin Tamil people in the North was evident in parliament last week, when Jaffna district MP Archchuna Ramanathan made unnecessary comparisons targeting the Fisheries and Ocean Resources Minister R. Chandrasekar, a Malayaga Tamil and Chair of the Jaffna District Development Committee. The MP’s behaviour came under severe criticism within the Tamil community in the North.

Within the community, there are strong calls to keep the ‘Indian’ tag on the basis that it would be a security guarantee and ensure the well-being of the community as well. As part of its development cooperation with the country, India has been assisting in the implementation of a number of projects, many of which are directly aimed at the welfare of the community, focusing on housing, education, vocational training, health, and community development initiatives.

Responding to a question in India’s Lok Sabha on March 4, 2020, the Minister of State in the Ministry of External Affairs said a total of 461,639 Tamils were repatriated to India from Sri Lanka under the Agreements on Persons of Indian Origin of 1964 and 1974 signed between India and Sri Lanka.

According to the Indian State Minister, Sri Lanka granted citizenship to 740,985 Indian-Origin Tamils and their natural increase through the Indo-Sri Lankan Agreement (Implementation) Act No. 14 of 1967, the Citizenship to Stateless Persons Act No. 39 of 1988, and the Citizenship to Stateless Persons Act No. 35 of 2003.

One such dissenting voice on the new identity is Professor A.S. Chandrabose, who studied and wrote extensively on the Indian-Origin community.

“Who gave the mandate to change the identity of the community? It should be left to the people themselves as they prefer to identify. These labels should not be thrown up merely for political gains and wishes of certain parties,” Prof. Chandrabose told the Sunday Times, pointing out that the 2011 census report indicated 839,000 people registered as Indian-origin Tamils, while others had registered under the Sri Lankan Tamils category.

Prof. Chandrabose also recalled the separate classification of “Bharathar’, a merchant group who identified themselves as having separate ethnic identities even though they were earlier designated as Indian-Origin Tamils. According to the census (2011), 7000 of them are registered.

“Just like Jaffna and Batticaloa Tamils have their own unique cultural identities, so do the Indian-Origin Tamils, and these identities should be protected and preserved for future generations, rather than worrying about label tags,” the professor remarked.

Former upcountry MP Thilkarajah, however, said that merely changing the name of the community was not going to get “us anything unless the features of true citizenship are ensured, including the right to own land, a shelter, and a dignified life. This will be more meaningful.”

He emphasised that the community people’s needs and political aspirations might differ depending on their current geographic location they live in.

An elderly farmer who settled at Malayalapuram in Kilinochchi, after surviving the 1983 ethnic violence, summed up the community’s collective wish with a local proverb that goes, “For how many years do we have to travel on footboard in the bus (indicating frequent repatriation of Indian-Origin Tamils after their citizenship was terminated in 1988)? Let us also come in. We are also citizens of this country.”

The best way to say that you found the home of your dreams is by finding it on Hitad.lk. We have listings for apartments for sale or rent in Sri Lanka, no matter what locale you're looking for! Whether you live in Colombo, Galle, Kandy, Matara, Jaffna and more - we've got them all!