News

Saltwater sours livelihoods and lives of 15,000 residents in Madampe

View(s):By Dilushi Wiejesinghe and D. Thiviyatharshini in Marawila

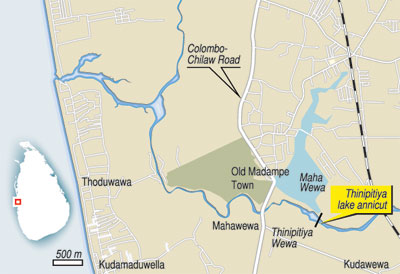

Residents of Madampe, Puttalam are grappling with a severe water crisis caused by salt water seeping into the Thinipitiya Wewa Scheme on the Kadupitiya Oya. The lack of clean water has disrupted daily life and livelihoods, leaving many in financial distress and uncertainty.

Authorities say that nearly 15,000 residents are hit. The impact has been especially devastating for Shaminda Darshana and Sanduni Kahandawala, who have a batik business with international partners. The 400 to 500 pieces of fabric they produced daily have dropped drastically to around 150.

“At first, it was salty water that came but now, sometimes, we don’t have water at all. We face daily water cuts,” Sanduni explains. Without fresh water, even the simplest tasks are a challenge. “The wax won’t boil off properly and a process that used to take ten minutes now takes an hour,” says Shaminda.

Thinipitiya sluice gate. Pic by M.A. Pushpa Kumara

“There’s no water to even go to the washroom,” Sanduni continues. Workers, covered in dye at the end of the day, have no way to wash before heading home. Financially, the strain is mounting. We’re struggling to pay our staff due to the water issue. I’m also in substantial debt,” Shaminda admits.

Desperate, the couple had to borrow water just to continue operations. “We borrowed water from our Grama Niladhari once,” Shaminda recalls. Their daily supply lasts barely 90 minutes, while they need 6,000 litres to run their business effectively.

More sectors affected

The batik industry is not the only sector suffering from the water shortage. The crisis has disrupted livelihoods across multiple industries, from agriculture to dairy farming.

A local cattle farmer explained how saltwater contamination has impacted milk production: “We use water from the wells in our homes to drink, but we don’t take their milk anymore because the saltwater affects its thickness.”

Meanwhile, farmers have been forced to abandon their crops entirely. An official of the Madampe Divisional Secretariat confirms that they were informed ahead of time. “At a meeting, we advised farmers not to cultivate during this season due to ongoing maintenance, so they have been made aware.”

However, a Water Board official claims they were excluded from these discussions “The Irrigation Department held a meeting with farming associations, asking them not to cultivate this season, but we were not notified.”

When the Sunday Times visited paddy lands, a sight of yellowing paddy due to saltwater intrusion against a backdrop of clear blue skies was to be seen. Villagers are expecting a speedy resolution from the irrigation department.

Failing infrastructure

Efforts to address the crisis have been largely ineffective, with some even failing outright, owing to the worsening condition of the barrier gates that keep saltwater out of the Oya.

An official from the Madampe Divisional Secretariat acknowledged the poor state of the infrastructure, “The gates are so dilapidated that if you push them with a finger, they could collapse.” The official spoke on condition of anonymity.

The Thoduwawa estuary, which naturally closes every six months (when sediment, mostly sand, accumulates at its mouth, forming a sandbar), has remained open, allowing saltwater to infiltrate the freshwater supply. The official identifies this as a major problem: “The estuary (where the Kadupitiya Oya falls to the ocean in Thoduwawa) naturally closes every six months, but now it stays open all the time.” But when the gates had worked well, saltwater intrusion hadn’t been an issue.

Repair efforts are slow and complicated. Of the five gates in the barrier, the third was removed for renovations. To facilitate this, the first and second gates had to be opened, allowing saltwater intrusion. The official explains, “There was no alternative.”

There are major logistical challenges to recent repair efforts. “It took 18 days for them to bring the third gate out. They couldn’t take big cranes to the site, and small cranes were not effective,” the water board official says. The struggle to replace failing structures allowed more saltwater intrusion. “Because the second and first gates were opened and used as a pathway to bring the third gate out, saltwater intruded because the tide was high.”

The Irrigation Department, which is responsible for the repairs, is under pressure to meet the project deadline or lose the allocated funds. “The work is likely to be completed in the next two to three weeks,” the official says. However, there have been no discussions about the risk of saltwater intrusion in the renovation plan.

The Water Board official, who also requested anonymity, said they had placed sandbags to support the salinity barrier but that this failed: “The sandbags were washed away by the tide when we visited the site this morning.”

The situation is worsened by long standing infrastructure failures and delayed projects. Efforts to build an additional pipe well to help with the water shortage were blocked by protests by villagers, the official said. “Had it been dug, the issue would have been resolved, to a certain extent,” he maintained. “That was our plan B.”

The estuary, initially carved out to prevent flooding, has not naturally closed for two years. “The purpose of cutting the estuary is to mitigate floods, and currently, there are none. However, fishermen now want to transform the estuary into a harbor,” the official explains.

The scheme’s history

Sarath Yapa, aged 79, is the Secretary of the Thaniyallaba Farmers Association, and an Ayurveda doctor who has studied the history of the scheme.

He blames the crisis on the destruction of a black stone across the estuary that stretched about a mile which was destroyed using dynamite. “People used to fish on either side of the stone, and it prevented saltwater seepage,” Sarath said.

However, former Speaker of Parliament Hugh Fernando, was prevailed upon by fishermen in the area to destroy the stone and to build a harbour in exchange for votes. “This was when saltwater began entering the annicut (Thoduwawa scheme)” he said.

Sarath says that the annicut has not been repaired in over twenty years. “The third gate got stuck about eight years ago, and the Irrigation Department asked our farmers’ association to fix it, promising they would cover the expenses. We repaired it, but we were not compensated,” he said.

Water distribution struggles

Authorities have now resorted to distributing water through various means. But supply–by the Water Board and Provincial Council–is inconsistent and logistical issues remain. Separately, 25 water tanks have been placed at various locations.

The Madampe Divisional Secretariat official explains the difficulties in getting water to the affected areas. “In Kakkapalliya and Halawatha, there is a water distribution source from the Water Board, and they have been providing water up to the Galahindiyawa junction”. However, the distance is an issue, leading to problems such as pumping difficulties and inconsistent water flow.

The Water Board distributes “5,500 cubic meters of water per day,” but it still isn’t enough to meet the demand. Overuse by some residents has made it even more difficult for those at the end of the system. “When people start getting water, they overuse it, leaving those at the end of the system with insufficient supply,” the Water Board official explains.

Typically, during a drought, authorities would close the annicut to collect water. However, that is no longer an option. “The doors of the annicut are rusted. If we don’t replace them, and they burst like a shopping bag, we won’t be able to do anything,” the official warns.

Though some residents have attributed the salinity issue to the Irrigation Department. the Divisional Irrigation Engineer Chandima Chandrasekara maintains that “the situation is under control and primarily a result of natural phenomena.”

He explained that salinity intrusion has been a recurring issue over the past three to four years, mainly due to deepening riverbeds caused by erosion. Additionally, the third gate has been leaking due to corrosion. The Irrigation Department oversees water flow management through the annicut.

Eng. Chandrasekara admitted that the anicut has not been maintained in over 20 years due to inadequate funding. “It is operated, but not maintained,” he said. He added that the maintenance manual for the anicut has not been passed down from the Irrigation Department to the Provincial Irrigation Department.

Repairing a single gate costs 20 million rupees. “We are depending on next year’s budget to repair the four remaining gates,” he added.

Meanwhile, the Water Board continues to monitor the water quality. While salinity levels have increased, officials confirm there has been no impact on pH levels.

The best way to say that you found the home of your dreams is by finding it on Hitad.lk. We have listings for apartments for sale or rent in Sri Lanka, no matter what locale you're looking for! Whether you live in Colombo, Galle, Kandy, Matara, Jaffna and more - we've got them all!