News

Handicapped legal aid unable to deliver what it promises

View(s):By Mimi Alphonsus

Sri Lanka’s legal aid mechanism helps hundreds of thousands of low-income citizens get access to justice. However, the system is held together by a thread, as a lack of funds and ad hoc implementation leaves many slipping through the cracks straight into prison.

The Legal Aid Commission is the main provider of legal assistance to low-income individuals. Anyone earning less than Rs. 40,000 per month is eligible for free legal advice and a lawyer’s services.

Rohan Sahabandu

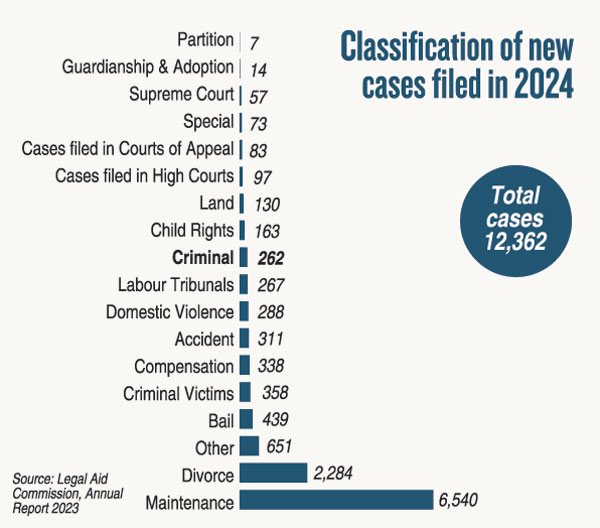

If your ex-spouse denies you maintenance, your landlord refuses to pay back your security deposit, your employer unfairly fires you, an insurance company refuses compensation for a road accident or your husband is abusive, it is the Legal Aid Commission that will provide you with free assistance. In 2024 the commission conducted 127,028 legal consultations and filed 12,362 new cases.

However, if you are charged with a crime and seeking a lawyer to defend you, your situation is less straightforward. You are not guaranteed free representation in all instances. Even in those that you are, the quality is often low.

In the High Court and Court of Appeal for instance, judges will assign a lawyer in the room to a defendant who does not have one. However, the lawyer will only be paid Rs. 5,000 in compensation regardless of how long the case lasts. This practice of “assigned counsel” has been in place for decades but is only applicable for court hearings alone. Suspects who want to apply for bail to the high court go through the Legal Aid Commission which regularly visits remand prisons to help.

If your case is being heard in the lower courts your situation is worse. Judges do not “assign” criminal defense lawyers in magistrate’s courts. As a result many impoverished defendants are left to represent themselves. “It’s a very pathetic situation,” explained criminal defense attorney Susantha Kumara who said its very common for people to appear in magistrate’s court without a lawyer. “Most people don’t know their basic rights or whether the offence they are charged with is even bailable or not.” Mr. Kumara said that in his 16 years of experience he has observed how some people admit the offence in the magistrate’s court simply because they can’t afford a lawyer or end up not receiving bail when they should have.

A few lucky defendants might be assisted by the Legal Aid Commission in such cases, but this is not common.

The Sunday Times called 10 Legal Aid offices in big towns around the country to find out if they would provide free criminal defense representation in lower courts. Five of them said they do not provide defense services except in high courts when assigned by a judge. Two said they can offer their services depending on the case, however, when asked if they would handle drug offences — one of the most common type of case — they refused. Only three said they would assist no matter the offence. In most other countries legal aid is mainly given in the instance of criminal matters, but in Sri Lanka criminal defence accounts for less than 3% of the Legal Aid Commission’s caseload.

Rohan Sahabandu, the chairman of the commission explained why there is less focus on criminal work. “One issue is that people don’t come to us with criminal matters as much. And the other reason is we don’t have the human resources.”

The commission is facing a severe staff shortage including for 38 legal officer and 30 management assistants positions. “Imagine trying to do criminal work on top of so many maintenance, divorce, labour, debt and domestic violence cases. We do want to be able to expand our criminal work,” said Mr Sahabandu.

In recent years it has proved difficult to hire lawyers and retain senior, experienced staff. After allowances, attorneys at the Legal Aid Commission are paid a small fraction of the salary paid to state counsels at the Attorney General’s department — the other legal professionals hired by the government.

Besides their staff, the commission also depends on a “pool” of private lawyers who take on cases occasionally for free. According to two such lawyers who requested anonymity, this “pool” mostly consists of very junior and inexperienced people, taking on legal aid cases to gain experience.

Overworked commission staff and inexperienced “pool” lawyers inevitably are unable to provide consistent, quality services. “I signed up for the pool immediately after taking oaths with no supervision. In one case I missed a deadline to appeal” said one lawyer. “But legal aid clients are so vulnerable. In the event where a case is not properly pursued they can’t say anything because it’s free. In reality they can’t exercise their rights in the way a paying client can.”

| Effective legal aid helps reduce costs Last year the Legal Aid Commission received Rs. 307 million to manage their 272 staff operating 86 centres. Funding has increased in recent years, but so have caseloads. Around the world, legal aid is generally underfunded, something the International Legal Foundation (ILF) has sought to remedy. They have been involved in setting up and supporting legal aid systems in several countries including Afghanistan, Myanmar, and Nepal. The Sunday Times spoke with ILF’s Executive Director, Jennifer Smith, and their Senior Programme Director for Asia Shikha Pandey to find out how. Although acknowledging the importance of legal aid in all fields, ILF prioritizes criminal defense over civil issues in line with international law that places an obligation on states to ensure that every person who is arrested or detained has access to legal aid. They also advocate that lawyers should be appointed at police stations or at first appearance in court as the hours after an arrest are crucial. These moments decide whether a person remains in detention or is allowed to go home, their ability to effectively defend themselves and receive a fair trial, and whether appropriate decisions are taken to determine if the case should be prosecuted at all, they said. “We often hear governments around the world saying the reason we don’t provide proper legal aid is because we can’t afford it, but we don’t hear them say we can’t afford the police to arrest people or we can’t afford the prosecutors to prosecute them,” said Ms. Smith. She added that effective legal aid helps countries reduce costs in the long run as it prevents unnecessary imprisonment and prolonged trials. In South Asia there is a crisis in access to legal aid which Pandey says is exacerbated by a negative perception of legal aid in Asia and around the world.. “People think that if this person is a legal aid lawyer, they will be a bad lawyer and that influences those who want to join,” explained Ms. Pandey, “this mindset is because strong legal institutions with a high quality of training and resources don’t exist. We need to support the establishment of effective legal aid institutions that lawyers are proud to work at so we can change this mindset.” | |

The best way to say that you found the home of your dreams is by finding it on Hitad.lk. We have listings for apartments for sale or rent in Sri Lanka, no matter what locale you're looking for! Whether you live in Colombo, Galle, Kandy, Matara, Jaffna and more - we've got them all!