Cruising down our canals through the mists of history

Although it is customary in this country to describe all our inland canals and coastal waterways in the western and southern districts as Dutch canals, this is a misnomer. A network of canals did exist for centuries in a more rudimentary form before the colonial rulers took control of these coastal territories. The claim that the Dutch were solely responsible for the construction of the existing waterways is a distortion of fact.

The Dutch East India Company’s (V.O.C.) over a century and half of rule of the maritime provinces of Ceylon, from 1656-1796, streamlined and improved the network of canals.

The Dutch East India Company focused their attention on the urban surroundings that linked Colombo’s Beira Lake to the harbour, effectively constructing a series of lock gates to balance the water levels. It was an intricate system without doubt that needed a thorough understanding of hydraulic engineering.

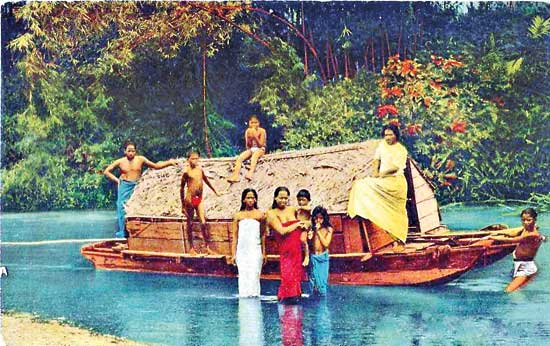

River transport: A padda boat converted to a house boat on the Kelani Ganga (1906)

One of the earliest historical records of the use of canals for water transport is by the Arab historian Abou–zeyd based on the authority of one of his informants ibn Wahab who had sailed along these waterways.

Emmerson Tennent in 1859 quotes the Arab account that vividly describes an inland voyage lasting several weeks:

..appears to have looked back with singular pleasure to the delightful voyages, which he had made through the still-water channels, elsewhere described, which form so peculiar a feature of the seaborde of Ceylon, and to which the Arabs gave the obscure term ‘gobbs’. Here months were consumed by mariners amidst flowers and overhanging woods, with enjoyments of abundant food and exhilarating drafts of arrack flavoured with honey.

In another reference, the Jesuit Father Fernao de Queiroz (1617-1688) in his monumental work – The Temporal and Spiritual Conquest of Ceylon (1698) gives the credit for the construction of the canals in the western seaboard to Parakrama Bahu VII, father of the king who ruled over the Kotte Kingdom when the Portuguese first made landfall.

Sebastio Barradas (1543-1615), the Portuguese historian in 1613 informs us “near Colombo the Fathers embarked on a canal by which they entered into the River Calany…. going down this, they proceeded into another Canal as narrow and shady and so came to Negombo.”

During his visit to Sri Lanka in 1646, he informs the reader that there was traffic on this canal network. This was ten years before the Dutch captured Colombo in 1656. It is therefore improbable that the Dutch who were yet to take control over the maritime provinces of the island could have had a hand in constructing these elaborate waterways.

Regrettably, our attempts to assess and analyse the significant development of the canal system is at grave risk as many of the historic links have a way of vanishing before our eyes mainly due to negligence and public ignorance of the laws that govern the protection of these canals.

The earliest waterways were created by damming and modifying the course of several networks of rivers. These canals were in use for centuries by the early inhabitants to transport passengers and materials from one destination to another.

The Elahara canal which lies between the Matale and Polonnaruwa districts, is a prime example of a waterway which over centuries had multiple uses: also acting as a regular thoroughfare moving men and materials over a vast distance.

By the 19th century, many of the government publications such as almanacs-gazetteers and directories, make special reference to the canals in use – informing us of the detailed measurements, fees that were levied for transport and travellers etc.

Strict laws were enacted to prevent altering the course of these channels. For instance, in the case of Muturajavella, originally a huge rice growing pasture, efforts to turn it into a profitable agricultural land by transplanting rice and other vegetables were mismanaged and it turned into a uninhabitable swamp, due to extensive flooding by saline water.

Many attempts were in place to combat the effects of the Kelani Ganga flooding the lowlands bordering the Colombo city but several schemes undertaken never totally proved successful.

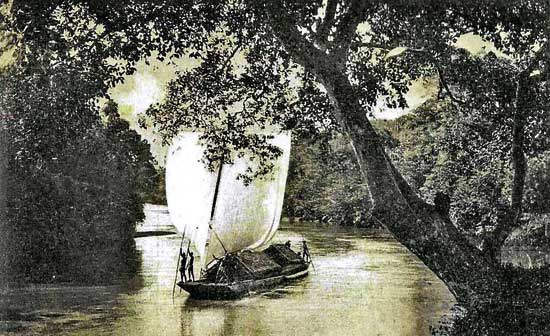

Padda boat with sail on the Kelani Ganga (1907). Both images, postcards by Plate Ltd., Kollupitiya

By 1903, the British Government had spent as much as £3000 (a huge sum by present-day currency standards) to maintain the canal network between Colombo and Puttalam. A decade later in 1911, a sum of £8000 was further deployed for this scheme from the funds available to the Public Works Department.

In 1950, the British traveller Major Roland Raven-Hart commented that of the 100 miles of waterways in operation, less than 15% was actually manmade. The rest were natural streams and water courses that were already there in an extensive wetland which in turn was excavated, broadened and improved to create the canal network

Raven-Hart also firmly believed that the waterways from Colombo northwards and probably also southwards were constructed by the Sinhalese and after centuries of use, later repaired and restored, first by the Portuguese, albeit not too successfully and later by the Dutch, who managed the network successfully and profited from the effort.

He reinforced his arguments by suggesting that if the Sinhalese whose engineering skills in hydraulic engineering were so highly sophisticated that they were capable of constructing the ancient irrigation network which traversed over several hundred miles, they would have been quite capable of constructing a network of canals in the identical manner in the western and southern coastal districts

Even before the pre-independence period and well up to recent times, there was brisk transport and trade in bamboo, timber, bricks, sand, stone and other building materials along the canals. There were boat-houses where the crew spent the night.

The old Parliament building in Galle Face required from the architects and builders huge granite blocks which were used to adorn the exterior. These massive slabs of stone were transported by barges from Karawanella where they were quarried and despatched by way of the canal network to be unloaded at the site alongside the Beira Lake.

When laying out the warehouses in Colombo, the architects selected the site bordering the Beira lake in the 1910-1920 period, which made it convenient for the water traffic from the Negombo canals to bring the plantation produce particularly tea, rubber and coconuts.

The waterway and the journey from Colombo to Puttalam and beyond was by way of the Hamilton Canal (established in 1850), then via the Kelani river to Negombo and further north to Chilaw and Puttalam.

The journey southwards from Colombo to Bolgoda lake was via the Kotte reservoir and then by way of the Ansthruther Canal to Kalutara.

During such a journey one would encounter four rivers – the Kelani Ganga, Maha Oya and Deduru Oya and further north beyond, the Kala Oya.

During the travel south to Galle, it would be the larger water courses: the Bentota Ganga, Kalu Ganga and Gin Ganga.

Sri Lanka was fortunate to inherit a network of rivers comparable to the spoke of a wheel.

Many of the rivers in the wetter districts were navigable for a considerable distance. The Kelani Ganga is navigable up to about 50 miles up to Ruwanwella and beyond, while the Kalu Ganga is navigable up to Ratnapura.

The Gin Ganga can take you all the way up to the edge of the Sinharaja forest and it is believed much of the timber extracted from there came down this river.

Several pleasurable journeys by water are described too by Ernest Haeckel, Carpenter, Prince Waldemar of Prussia, Wilhelm Geiger and other 19th century authors and travel writers who visited Ceylon.

In 1872, the Bishop of Colombo Hugh Willoughby Jermyn with a view to showing his guests the scenic beauty of the island, decided to take the unusual step of doing a circuit and visiting the churches along the west coast by travelling along the canals in a padda boat, which was christened ‘the Castle Jermyn’. His daughter had invited Gordon Cummings, an amateur landscape painter and writer to accompany the party. The converted accommodation soon evolved into a houseboat with all the necessary fittings and furniture.

The voyage started with the group embarking at the Kelani Ganga, then travelling via the Dutch canal into the Negombo lagoon, and then to Kalpitya and on to Puttalam, after which they continued their visit to Mannar and Jaffna most likely by boat.

It is a pity that these ancient networks of waterways and canals are not developed and better utilised in this time of burgeoning tourism in the country.

Searching for an ideal partner? Find your soul mate on Hitad.lk, Sri Lanka's favourite marriage proposals page. With Hitad.lk matrimonial advertisements you have access to thousands of ads from potential suitors who are looking for someone just like you.