Telling the truth with a form that allows formlessness

View(s):Ever since she began researching for The Hamilton Case, her first book which included Sri Lankan content, Michelle de Kretser has checked details with me whenever she produces similar work on the grounds that, since she left Sri Lanka at the age of 14, her recollections of the island are murky. Consequently, when she asked me to verify some facts about E.W. Perera’s trip to England in 1915, I assumed that her seventh novel would be a historical narrative on the imprisonment of Buddhist leaders during the 1915 Riots, the declaration of martial law, and Perera’s perilous journey during the First World War with the “shoot-at-sight” order sewn into his shoe – details that have become part of Sri Lankan folklore.

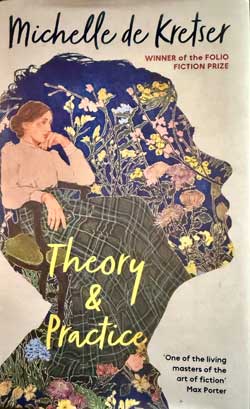

This historical moment is referenced in Theory and Practice but subordinated to Virgina Woolf’s derogatory diary entry in which she describes Perera who visited their home in 1917 to petition her husband Leonard on the situation in Ceylon as a “… poor little mahogany coloured wretch … the same likeness to a caged monkey, suave on the surface, inscrutable beyond.” Even his gifting Virginia with a souvenir from Ceylon (a common practice then and now) is interpreted as a bribe. The unnamed narrator/chief protagonist makes this discovery while researching Virginia Woolf’s writings and it serves as a point-of-departure for an exploration of a variety of concerns related to precept and example, theory and practice.

Robert Frost’s poem “The Road Not Taken” comes to mind on reading the first 22 pages. We encounter a young Australian geologist exploring an exotic landscape of “chalets, cows, ice-blue lakes, hillsides of coloured flowers” in Switzerland; in the process, he keeps obsessing over a Spanish music teacher he had met in 1957 with whom he is still in touch, and an earlier episode where he had impulsively stolen a ring from his grandmother, a theft that is blamed on a domestic.

Robert Frost’s poem “The Road Not Taken” comes to mind on reading the first 22 pages. We encounter a young Australian geologist exploring an exotic landscape of “chalets, cows, ice-blue lakes, hillsides of coloured flowers” in Switzerland; in the process, he keeps obsessing over a Spanish music teacher he had met in 1957 with whom he is still in touch, and an earlier episode where he had impulsively stolen a ring from his grandmother, a theft that is blamed on a domestic.

The narrator unexpectedly intervenes at this juncture, however, shifts into the first person, and truncates this promising narrative. Her decision is influenced by reading in a 2021 issue of The London Review of Books of how an Israeli commander who had immersed himself in “canonical works of poststructuralist and urban theory, including Situationist texts,” as a student, had used this knowledge to destroy the homes of Palestinians in pursuit of his military goal. She concludes, “I began to see that my novel had stalled because it wasn’t the book I needed to write. The book I needed to write concerned the breakdowns between theory and practice.” To achieve this end, she “wanted a form that allowed for formlessness and mess. It occurred to me that one way to find that form might be to tell the truth.”

As a child, after being sexually molested by a British music examiner in Sri Lanka, the narrator found a degree of solace when another girl had reached out and indicated that she had been abused too: “The way to counter shame was to seek out solidarity” because telling the truth at that age would have resulted in punishment of the children or in their accounts being disbelieved. The little girl, now an adult writer, will not hold back in exposing such abuse whether it is from her own past or in recounting the paedophilia of the famed Australian artist Donald Friend in Sri Lanka and Bali.

An obvious example to follow is Virginia Woolf (herself molested when young) who was instrumental in providing a form for generations of women to fearlessly express their views. But Woolf’s diary entry on E.W. Perera complicates matters for her because, as a Sri Lankan expatriate, she can identify herself with Perera as well. That her thesis supervisor Paula, “Melbourne’s Designated Feminist,” discourages her from focussing on Woolf’s comments because “such thinking was everywhere at the time” does not help. She ultimately negotiates these academic pitfalls and completes “Adventuring, Changing: The Gendered Self in the Late Fiction of Virginia Woolf,’ a study that perfectly satisfied “the requirements of the university. [But] I think of it now with a shiver of shame.”

The narrator grapples with similar dilemmas throughout her life. She is heartbroken when her boyfriend cheats on her by sleeping with Lois although theoretically emotions have no place in postmodern feminism – “While trusting in feminism’s transformative power, I retained a stubborn, dazed belief in love.” But she then begins a torrid, intermittent, clandestine sexual relationship with Kit, an engineering student, whose “official” girlfriend Olivia was known to her.

At one level, the narrator’s dalliance with Kit makes perfect sense. The novel is mostly situated in 1980s St Kilda, Melbourne, a pulsating bohemian world of radical ideas, innovative art historians (like Lenny), and others who demonstrate unconventional approaches to music, film and literature. It is a world of raucous parties made possible because junkies “frighten away the gentry.” Readers may identify the author’s irony in Kit’s claim of having a “deconstructed relationship” with Olivia to rationalise his sleeping with the narrator. But it makes perfect sense in this zany world.

For the narrator, however, the relationship provides more than sexual fulfilment. She also pursues it to “punish” Olivia, the golden tressed, rich girl, whose life path is apparently secure whereas the narrator, an expatriate from Sri Lanka, anticipates an arduous struggle given her financial situation and lack of contacts. The author captures her jealousy, self-loathing, pity, temptation to infiltrate into Olivia’s home in her absence to cause mischief, and other feelings with great aplomb. It’s only at the end that she feels remorse for treating her as a hated rival for Kit’s affection as opposed to a fragile human being when she discovers that Olivia had committed suicide.

At one point, the narrator quotes Woolf’s famous line, “We think back through our mothers if we are women.” Small wonder then that the inextricable, sometimes infuriating (for the daughter), relationship between the mother and the narrator is another theme that is explored in the novel. The tensions are not merely generational. The narrator’s mother had emigrated to Australia from Sri Lanka as an adult, so fitting into a new country, and a different culture is a challenge. Then again, she must adjust to her daughter living away from home, a child who has become increasingly abrupt in interacting with her.

The evolution of this relationship is fascinating. Initially, the narrator thinks of Virginia Woolf as a surrogate mother—the Woolfmother as she calls her—but as already discussed, modelling herself on Woolf works only for part of the time. While the reader can empathise with the narrator’s impatience to live her own life without being incommoded by such maternal interventions, the mother’s widowed loneliness, compulsion to connect with her daughter via recipes, telephone calls and unsought advice also strikes a chord. To the narrator, initially, “the name for that entwined closeness and distance was weirdness.” Although she indulges in “a little torture” on her mother through unkind words, she realizes that the bond with her mother is ineluctable. She becomes fiercely protective of her towards the end and, in effect, becomes mother to her mother.

Theory and Practice will appeal to a wide readership but especially to those, like the narrator, who completed first degrees in English in conservative, or liberal humanist-oriented universities, in the early 1980s, and discovered that “Theory had taken book, essay, novel, story, poem, and play, and replaced them all with text” when they embarked on postgraduate study. Individuals who were totally invested in the adage that literature is “felt life” struggled with their research since they could not adjust their approach to meet the requirements of the new dispensation; others, especially those who relished abstract thought, embraced theory without reservation; still others, like the narrator, recognised what post-structuralism had to offer but were mindful of its limitations.

If this very contemporary novel posits an old-fashioned moral at all, it is to appreciate the importance of adopting a middle path in one’s life.

(The reviwer is Professor Emeritus, University of Peradeniya)

| Book Facts | |

| Theory and Practice by Michelle de Kretser Sort of Books, 2025 Reviewed by Senath Walter Perera |

Searching for an ideal partner? Find your soul mate on Hitad.lk, Sri Lanka's favourite marriage proposals page. With Hitad.lk matrimonial advertisements you have access to thousands of ads from potential suitors who are looking for someone just like you.