|

6th June 1999 |

Front Page| |

Tattered remnants, shattered livesAll that these families who have experienced "disappearances" ask for is compensation to pick up their lives. By Kumudini HettiarachchiBADDEGAMA: Quiet flows the Gin ganga (river) just a stone's throw from her home, now gone to rack and ruin. But the beautiful waters of the river bring only memories of tragedy, for they were the very waters that bore her 23-year-old daughter's body.

"First they took my Janak putha (son) near the boutique in April 1989. Then they came to the house next door where my daughter, Sandhya (23), was spending the night with two elderly aunts and took her away in the middle of the night. Later we heard that her mutilated body was floating down the river. I didn't have the heart to go and see her. But her brother did and he came back angry - her mouth and throat were slit. We were scared to take her body out of the river, for fear of the army coming after us," Somi stuttered through betel-stained lips, overcome by emotion, even so many years after. Tragedy that dogged her life did not end there. Mahinda, the son who watched impotently as his sister's body floated away, was upset and angry over the injustice. "It is not important whether I am dead or alive," he told his grieving mother and joined the "kandayama" (group), she says, referring to the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna. Next the army came for him. They surrounded their home one night and took him away. That was the last she heard of him. That was years and years ago. She has been paid Rs. 25,000 for each of her missing children. "For what?" she asks. Memories and the ache here still remain," Somi says, touching her chest with wrinkled hands. Her brick home and large garden bear witness to the fact that she has nothing to live for. Unwashed clothes are strewn all over the tiny house, the roof of which is broken here and there. The trees are laden with unplucked coconut and rotting jak fruit. The footpath, the only access to the house, is overgrown. No lamp has been lit at the tiny shrine near the front door for many years. It is the same in the home of 45-year-old Danawathie Palliyaguru, except that a lamp burns near the large black and white framed photograph of a young man. Seated on a worn settee in her home surrounded by paddyfields and a small plot of tea bushes, she describes the events of that Christmas night 10 years ago, as if they happened yesterday. "They threatened to break down the door if we didn't open it. It was around midnight on December 26, 1989. When we opened the door, four armed men rushed in. They made us kneel, even my youngest child who was just three years old." Pointing to the photograph, she says, "That's him, my husband who was the Grama Sevaka (a village-level official). They said they were from the army and wanted to question him. They took him out into the garden. My four children were screaming. In the panic, we didn't notice the men near us had left after awhile. When we peeped out of the house, they had gone. They had taken my husband with them." "Cautiously we went across and informed our in-laws who live close by. The neighbours had not seen people moving along the single track that leads to the house. So they must have taken him across the paddyfields. There was no trace after that. We went to the police that night itself, but they refused to take our statements. They recorded it only a day later," she recalls wiping a tear from her cheek. Then the search began. They looked in wells, they looked in fields. They rushed to the river's edge whenever they heard bodies were floating down. They even paid "kappam" (extortion money) for any news. But nothing came. They also wrote to the Human Rights Commission. The family has been paid Rs. 50,000 as compensation. They exist on that, his salary of Rs. 6,000 which is being paid to them and the little income they get from selling tea leaves from their three-quarter acre plot. "Life is hard. My eldest son, who was 10 at the time his father was taken away refuses to stay at home. Now he's 20, but he still shudders at the thought. Their education was disrupted. How can you bring up children, especially sons, without their father?" Danawathie cries. For Hewapathiralage Ariyawathie (54) life took a tragic turn on August 31, 1990. She had bid her husband, a mechanic, goodbye at home earlier, for he was away to the airport on his way to Thailand for a job. The next day they were informed by the police that he had been arrested at the airport. They rushed to the police station. He had been brought back to his village from Colombo, blindfolded, by the police in a private vehicle belonging to another villager. Chandrapala Jagoda told them from the police cell that at the airport he had been shown a photograph. It was an old one taken in the early 70s, when he and several others had been putting up a pandal. Security personnel at the airport had asked him whether he was in the picture and when he said he was, they had arrested him saying that they had got orders "from the top". Relatives and Ariyawathie, fondly called Kalu Akka (Dark Sister), visited him for 11 days. They saw him in a bad state after being assaulted during interrogations. The last day that they saw him he had been hit on the face with a knuckle-duster. His teeth were broken and his clothes were blood-splattered. He was in severe pain. His hands and legs were chained. When they went to visit him on the night of the eleventh day, with coriander water, the police told them, "Mehe ethi Jagoda kenek ne". (There is no Jagoda here). They then began their search for justice. They contacted politicians and filed a case in court. During the case the police had said that when they took Jagoda to some spot to identify some weapons he escaped from the vehicle. How could a man, beaten so badly and hardly able to walk, jump out of a vehicle? Ariyawathie asks, while her daughter looks on in sorrow. Though Thanusha, the daughter was only 11 at that time, the visits to the police are imprinted on her mind, she says her fists clenched white. They too have written to the Human Rights Commission and been paid Rs. 50,000 as compensation. But Ariyawathie murmurs, "I have four children. Their education has been ruined. Is that enough? The only things we have now are the blood-soaked clothes he wore during the last few days of his life. Though tattered they are very precious." What are their hopes? No, they do not have hopes of ever seeing their loved ones again. They only ask for adequate compensation from the state to pick up the shattered pieces of their lives. |

||

|

Front Page| News/Comment| Editorial/Opinion| Business| Sports | Mirror Magazine |

|

|

Please send your comments and suggestions on this web site to |

|

For

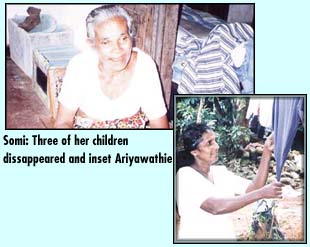

M.P. Somi (63), mother of nine children, three of whom are no more, the

river brings heartache and sorrow. Hot tears streaming down her face, silver-haired

Somi talks of that terrible period when two of her sons and a daughter

disappeared.

For

M.P. Somi (63), mother of nine children, three of whom are no more, the

river brings heartache and sorrow. Hot tears streaming down her face, silver-haired

Somi talks of that terrible period when two of her sons and a daughter

disappeared.