|

Old Dutch map sheds light on Kotte's

past

By Dr. K. D. Paranavitana

The capital of the kingdom of Kotte,

Sri Jayawardhanapura or the 'City of Victory' emerged

due to the strenuous efforts of Nissanka Alakeshvara

(1340-80). It reached its zenith of prosperity during

the reign of King Parakramabahu VI (1411-66) whose rule

has been eloquently described by historians and sung

by poets of the time.

Kotte as the capital city ceased to

exist from 1565 when it was abandoned with the removal

of nominal ruler Don Juan Dharmapala to Colombo by the

Portuguese. The city was virtually razed to the ground

by the Portuguese in the latter part of the 16th century.

Hardly any original structure of the city is left standing

at present for us to see. The grandeur of the palace

and temples which existed in the halcyon days of King

Sri Parakramabahu VI could be imagined only from the

writings of courtiers and poets.

|

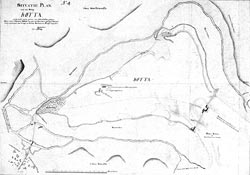

| Elias’s map of Kotte |

The citizens of Kotte struck with

dismay at the ruthless destruction of their noble edifices

and sacred temples escaped to villages in neighbouring

districts fearing for their lives. Kotte perished and

the neglected lands and heaps of ruins were gradually

covered with wilderness. During the Dutch period it

became merely a village accounted for revenue purposes.

"It is both strange and unfortunate,"

writes H.C.P. Bell in his Annual Report of 1909, "that

among the fairly numerous plans of the chief towns of

Ceylon left by Portuguese and Dutch writers, not one

of Kotte has come to light." Researching the subject

at the National Archives of the Netherlands in The Hague

this writer was, however, able to trace an interesting

location map of Kotte which seems to have been copied

by land surveyor Pieter Elias circa 1790.

The legend on the map states, "the

situation plan of the village Kotte located one and

a half hours distance from Colombo. The exact situation

of Kotte together with surrounding villages with fruit

and wild trees grown in rough and uneven manner. - P.

Elias".

Elias in his map indicates the exact

situation of the citadel, its surrounding villages like

Battaramulla to the east and Nawala to the west and

on the north and south west with fortifications and

a gateway. A road led right across the village starting

from the direction of Colombo and continued towards

Galkissa and further to Salpiti Korale. Passing the

gateway on the side of Colombo was a toll and rest house.

The village shows only the important

buildings such as the site of the palace, warehouse

of the company, a school and a dried tank. Close to

the entrance on Etul Kotte, a cinnamon plantation is

shown. Elias, however, has not indicated the ancient

ruins and the places of worship merely because such

places were considered of heathen interest and of no

economic value. The layout of the citadel that existed

during the heyday of the kingdom was preserved at the

time Elias made this map.

The places shown on the map are as

follows:

1. The Village Battaramulla

2. A section of Pita Kotte

3. Village Kotte

4. Village Navala

5. Paddy fields which ultimately join Kelani River at

Nagalagam pass

6. Cinnamon Gardens

7. Seat of Government -King's Palace

8. Dried Tank

9. Warehouse of the Company

10. Gravet and the Rest House

11. The meeting place of two tributaries

12. The road to Galkissa and further towards Salpiti

Korale

The descriptions of Kotte embodied

in the Nikaya Sangrahaya and in the Diogo de Couto's

(1543-1616) The History of Ceylon tally with this map.

Elias naturally had paid special attention to taxable

lands of Kotte and places of interest to the company.

What is lacking in the map is information on Buddhist

places of worship and details of ruins.

It may be of some interest to the

reader that contents of this map be studied in relation

to the Dutch tombos compiled for the purpose of collecting

taxes for the company during the period 1755-76. The

Portuguese were succeeded by the more ordered administration

by the Dutch. At the beginning of Dutch rule in 1656,

Kotte was still a ruined city covered with shrubs. Certain

early Dutch maps indicated Kotte as 'Ruins of the Palace

of Cota'. It was somewhat later the Dutch set about

to restore the dues from Etul and Pita Kotte and particulars

duly taken into the tax registers called tombos. Unlike

the Portuguese, the Dutch went into more detailed and

exhaustive recording of information on lands and their

owners, classified into two categories -- one for the

names of the land holders and the other for their gardens

and paddy fields called, head and land tombo respectively.

The lands in Etul Kotte and Pita Kotte are registered

under the Palle Pattuwa of Salpiti Korale distinguishing

the two divisions, citadel and their outskirts.

The Dutch tombos reveal some fascinating

information in relation to demography and social mobility

in the early days of the Dutch administration and even

before. Some families abandoned Kotte in Portuguese

times and lived in exile in districts such as Walallawiti,

Pasdun and Hewagam Korales where tranquillity prevailed.

When normalcy was restored, these families returned

and occupied their former holdings. The tombo of Etul

Kotte compiled in 1765 records 41 families and in its

revision made in 1765 the numbers increased to 62 with

34 occupying Pita Kotte. Their land holdings were recorded

in tombo after on-the-spot investigations by the tombo

commissioners.

The ge-names or wasagamas recorded

in the tombo indicate several interesting factors. Ge-names

such as Bulatsinhalage, Welmillege, Pelenda Pathirage,

Nugegodage, Waduwage, Butgamage, Nawalage, Kalubowila

Vidanelage and Wellabaddege have no relevance to Kotte

itself. In the presence of tombo commissioners these

families identified themselves with the name of the

village in which they lived in exile. They returned

to Kotte and re-occupied their former family land holdings.

According to the land tombo of Etul

Kotte, some resettled householders obtained certificates

of letters of authority from the Dutch official in charge

of the district long before the compilation of tombo

in 1765. These documents have been of immense use for

them to substantiate their claims to the land holdings

which were usually recorded in nota bene. These ge-names

are also acceptable evidence to suggest that these families

fled to districts far away from Kotte including Walallawiti

and Pasdun korales, Welmillage, Bulatsinhalage and Pelenda

Patirages. Most of the families that fled belonged to

the govi caste who were either in the military (Hewa/Aratchi)

and civil official class (Nilame/Lienege). When they

re-established in Kotte, service castes were also reintroduced.

They were given less prominence in the list of land

holders. Names of those who did not possess lands are

recorded with a separate entry Heeft geen bezittingh.

(has no land holding).

Another interesting factor is the

naming of lands with names of ancient buildings constructed

on the particular land. Moehandirange Willem Rodrigo,

a schoolmaster of Govi caste owned a land called Pasmalpajewatte

(Garden of five-storied palace, a family inherited land).

Colombe Tantrige Laurens Perera who lived in the vicinity

owned Pasmalpaje Werehe Kongahawatta (Garden of five

storied temple, Kongahawatta). This resembles the garden

on which the temple residence of the great poet Ven.

Sri Rahula who gave us a fascinating record of the glory

of Kotte in his poem Salalihini Sandesaya was.

Certain lands were named Parangiawatta

(Garden of the Portuguese). Pelenda Patirage Mighiel

Dias owned a land in Etul Kotte called Adriaen Ponsoeparangiawatte

(Garden of the Portuguese named Ponsoe) and at the time

of the tombo registration, the name changed to Telemboeghawatte.

Pattijege Christoboe Silva was in possession of a land

named Kitoelgodde Parangiawatte (Garden of the Portuguese

of Kitulgoda).

Those registered land holders of Etul

and Pitakotte never changed the Portuguese ‘cognomen’

given by their ancestors. The Dutch also never issued

proclamations prohibiting the use of Portuguese names.

Some of the names are as follows: Soeseuw de Almedage

Francisco Perera, Gasparoege Siman de Coste, Don Anthonyge

Don Joan and Don Constantino Madere de Basto.

One of the most prominent families

of Kotte was the Magellege family which inherited paraveni

lands situated near the palace and the Dalada Maligava

of Etul Kotte. Therefore, this family received a foremost

rank in the list of names recorded in the tombo. The

Magellege family owned a land holding referred to as

Maligawatta or the 'Garden of the palace' with adjacent

land called Gabadawatta, or the 'Garden of Treasury'.

It is said, the family escaped Kotte

fearing of the wrath the invader, retired to more remote

villages situated far away in Walallawiti and Pasdun

Korales where the Portuguese terror did not exist and

returned when Kotte was brought back to normalcy. At

the time of compilation of tombo Magallege family confirmed

their right of ownership of their land holdings with

documents.

The maps and tombo when combined can

extract good results in respect of the social mobility

and demographic pattern that existed in colonial Sri

Lanka in the 16th and 17th centuries. It also shows

a remarkable growth of re-occupation of the village

Kotte at the end of the Dutch period.

|