| When Lanka’s

haven of herbs became the centre of research

By Dr. K. D. Paranavitana

It is a little known fact that the

Dutch Hospital in Colombo once functioned as the centre

of botanical studies in Sri Lanka. Therefore, it is

appropriate that this article follows the ‘Dutch

Hospital by the side of the harbour’ published

last week.

After the Dutch took over the administration

of the maritime regions of the island in 1656, the importance

of studying Sri Lankan flora and fauna was highlighted

especially by writers Phillipus Baldaeus in his True

and exact description of the great island of Ceylon

(1672) and Wouter Schouten in his Remarkable Voyage

(1676). Robert Knox in his work An historical relation

of Ceylon (1681) paid serious attention to the Sri Lankan

herbaria.

|

| Drawing of Cinnamon plant from

Burman, 1737 |

“All their cures,” says

Baldaeus, “consist of pure empirics and experience.

They possess great written folios, which had been passed

to them from their fore-fathers, to which they have

added the results of their own researches. All their

purgatives are administered either in pills or mixtures,

which are composed of various medicinal herbs; in the

case too profuse a discharge of the bowels, they advise

the patient to apply a little black pepper ground with

water on or about their navel. I have myself experienced

this to be a sovereign remedy and it is good for all

cases of Tormina Ventris or stomach troubles and for

checking strong stools.” (Baldaeus, Tr. Ch. 47,

p.376)

Commenting on the Sri Lankan herbs

Robert Knox observes that, “The woods are their

apothecaries shops, where with herbs, leaves and the

rinds of trees they make all their physic and plaisters

with which sometimes they will do noble cures….A

neighbour of mine Chingulay, would undertake to cure

a broken leg or arm by application of some herbs that

grow in the woods, and that with that speed, that the

broken bone after it as set should knit by the time

one might boyl a pot of rice and three carrees, that

is about an hour and half or two hours; and I knew a

man who told me he was thus cured.” (Knox, Ch.

V, p. 28)

|

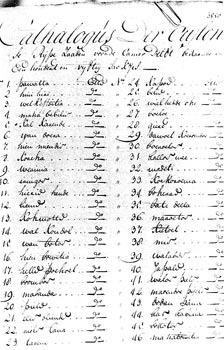

| Page from the catalogue of seeds

sent to Botanical Garden in Leiden,1746. |

Robert Knox, published his work An

historical relation of Ceylon, in 1681 embodying his

findings on the native medicinal plants. This work which

was translated into Dutch in 1692 drew the attention

of botanists in the Netherlands for the medicinal and

exotic plants, trees, vegetables, fruits and spices

of Sri Lanka.

Quite apart from the writers referred

to, the administrators were also interested in different

aspects, mainly the personal and economic factors associated

with Sri Lankan botanical studies. The crews of the

Dutch East Indiamen generally suffered from scurvy and

other shipboard diseases. For example, ten East Indiamen

from the Netherlands carrying 2653 persons suffered

heavy casualties and 1095 or 43% of them died before

reaching Cape of Good Hope while 915 survivors were

admitted to the hospital — such was the situation

in the Cape in 1782. The Cape of Good Hope was then

considered as the ‘Tavern of the Indian Ocean’.

The next major comfortable port of

call for the seafaring Dutch population to the East

was Colombo. The sailors who landed in Colombo were

in need of fresh water, green vegetables and fresh meat.

These contributed more to their recovery than a doctor

with his medicines. Probably the increasing mortality

on board during the second half of the 18th century

was due to chronic ill-health of many men on the ships.

Therefore, the Dutch authorities had to expand the hospital

in Colombo and enhance the studies in medical herbaria

to reduce the heavy cost of medicines, imported from

Europe.

The first considerable report by a

Dutchman on the natural science of the island was compiled

by Robert Pathbrugge in 1668. He reported on the possibilities

of finding iron and saltpetre and proposed improving

forestry and collecting information on useful plants.

A substantial contribution was also made by Hendrik

Adriaan van Reede tot Drakenstein during his sojourn

in Sri Lanka as the High Commissioner of the Dutch East

India Company in 1685.

He became a world famous botanist

after his well-known work Hortus Malabaricus (1678-1693),

extending to twelve volumes dealing mainly with Asiatic

flora. He inspected southern Sri Lanka in 1685 and collected

plants for the botanical garden in Amsterdam. In his

capacity as the High Commissioner, he issued an ordinance

commanding high ranking officials to prepare an annual

list of plants and seeds with their names and despatch

it to the headquarters in the Netherlands.

This collection from Colombo went

in two directions, one to Stadhouder Willem III (1672-1702)

who gave it to the botanic garden in Leiden. The other

went to the botanic garden in Amsterdam. The orders

and the good work started by Van Reede continued having

the Dutch Hospital in Colombo as the responsible centre.

The Swedish doctor Herman Nicolai

Grimm attached to the Colombo Hospital (1674) started

collecting medicinal plants, vegetables and minerals

and combined all his experiences in a handbook titled

Labaratorium Chymicum (1677). This was perhaps the first

serious work on the study of natural sciences in Sri

Lanka and was printed at the Dutch East India Company

press in Batavia, present Jakarta in Indonesia.

The foundation for the study of natural

science in the island was laid by Paul Hermann, a German

Doctor attached to the Dutch hospital in Colombo, between

1672 and 1680. He built up a collection of animals preserved

in nitric acid together with a large collection of dried

plants. He was more interested in Sri Lankan flora,

especially plants with medicinal properties. He consulted

the local physicians and learned the etymology of their

Sinhala names and their applications in various tropical

diseases. He despatched a large portion of his collection

to Arnold Syen, Prof. of Botany in the University of

Leiden and to Jan Commelin who was a well-known chemist

in Amsterdam.

Syen was succeeded by Paul Hermann

to the chair of botany in the University of Leiden in

1680. He took his entire collection of Sri Lankan plants

and animalia to his official residence in Leiden. This

collection went under the auctioneer’s hammer

after his death and disappeared. However, the catalogue

of plants he prepared was published posthumously under

the title Musei Indici (1711), and Museum Zeylanicum

(1717) providing a source of information on studies

of the natural science of Sri Lanka.

The lists sent to the Netherlands

consisted of an average of 150 plants at a time. At

a later stage these reports giving plant names had a

short description of their medicinal value. It is remarkable

that Professor Pieter Hotton of the University of Leiden

wrote a comprehensive research paper on the medicinal

value of Ackmella in curing stones in the kidney referred

to as renal calculus, to Philosophical Transactions

in 1702.

At the end of the 17th century, during

the tenure of office of the Governors, Laurens Pijl

(1680-1692) and Thomas van Rhee (1693-1697) they initiated

a step forward and prepared in two volumes codex of

beautiful water colour drawings of Sri Lankan plants

with short descriptions. Prof. David van Royen of the

University of Leiden received a few boxes of Sri Lankan

plants in 1769, 1771, and 1777. Simultaneously, Amsterdam

Professor Johannes Burman received similar boxes in

1771 and 1773.

Knowledge on Sri Lankan plants was

enhanced with the publication of Johannes Burman’s

Thesaurus Zeylanicus in 1737. He added an alphabetical

summary of well-known Sri Lankan plants to his work

with the help of a contemporary Swedish botanist Carolus

Linnaeus who stayed at his residence for some time.

Linnaeus was an indefatigable researcher who went after

the missing collection of Sri Lankan plants belonging

to Prof. Paul Hermann. A few years later he found it

with an auctioneer in Copenhagen. These two botanists

joined together and published an excellent work on Sri

Lankan botany titled Species Plantarum (1753) which

marked a substantial turning point in Sri Lankan botany

to modern botanical studies.

The last Dutch botanist associated

with the Colombo Dutch hospital was Carl Per Thunberg

who studied Sri Lankan flora between 1777 and 1778.

The plant and the flower that any Sri Lankan knows as

Thunbergia, is named after him. His collection of Sri

Lankan flora was considerably large and on his return

to the Netherlands it was gifted to the botanical garden

in Amsterdam and a part of it to his friend, Doctor

Martrinus Houtthuin who published them with descriptions

in his work Natuurlijk Historie (1761-1785).

In 1796, the British took over the

territory under the control of the Dutch and in 1811

William Kerr, on orders of the king of Britain established

a botanical garden in Slave Island in Colombo by the

side of the Beira Lake. This was named after the Royal

Botanical Garden in Kew, London and the street name

‘Kew Road’ in Slave Island still exists.

This longstanding combination of botanical

studies between Leiden and Colombo, begun by Prof. Paul

Hermann was expanded laying a solid foundation for botanical

studies in the island. This tradition was continued

with the help of Smithsonian Institute in Washington

and the State Botanic Garden in Leiden by producing

a standard work for Sri Lankan botany titled A revised

handbook to the flora of Ceylon under the editorship

of Fosberg and Dissanayake running into fifteen volumes.

|