Engaging space and identity of the ’60s and ’70sImagining Modernity. The Architecture of Valentine Gunasekara by Anoma Pieris (Pannipitiya, Stamford Lake (Pvt) Ltd and Colombo: Social Scientists Association, 2007), 174 pp. Valentine Gunasekara describes how as a child he was mesmerized by the beauty of a monastery at Varana especially the manner in which ‘the landscaping and irrigation works had been integrated with the elements of the cities’ (p. 17). Later he would study architecture at the Architectural Association (A.A.) in London and become the modernist architect and anti-hero upon whom Dr. Anoma Pieris casts a fragmentary gaze in her book Imagining Modernity. The Architecture of Valentine Gunasekara. The author, a lecturer in the Faculty of Architecture, Building and Planning at the University of Melbourne and trained at Moratuwa, MIT and the University of California Berkeley writes about architecture with brio while at the same time exploring Sri Lanka in the mid-1960s and 1970s - one of the most understudied periods of recent social and political history.

Gunasekara started his career building houses for the ‘generation of the 1940s and 1950s’ men and women who succeeded the colonial intelligentsia in the early post-independence years and described by Senake Bandaranayake as the ‘first generation of modern intellectuals’, products of free education and Sri Lankan universities. Many of them studied at the University College or Colombo and Peradeniya University. They were more or less bilingual although generally more at ease conversing in English, well versed in western classical literature, more cosmopolitan, however, than Sri Lankan in their outlook. It is the decline of the values they embodied and in some cases the nostalgic return of some individuals to a real or imagined ‘Sri Lankan ethos’ that this book narrates through the story of one ‘uncommon’ individual - to borrow Eric Hobsbawn’s expression. This book is a clear demonstration that in the postmodern world we gain from an understanding of the potency of the fragment as a diagnostic site for exploring the conditions of a whole system. Gunasekara’s life and ideas help us understand what is gone forever and what is left. In this sense the study complements historical and anthropological studies (from Michael Roberts writings to the more recent works of H.L Seneviratne) that have charted the rise of counter-elites in the mid fifties culminating in the Sinhala Only act and the political and cultural reconquest of the Sinhala majority. Until now the period from the mid-1960s to the close of the 1970s has remained shrouded in a haze, uncritically praised or condemned, except perhaps in the perceptive writings of Newton Gunasinghe on class structure during the 1970s which describe how by the mid-1960s the ‘new class alignments that commenced in 1956 had acquired a crystallized character’. As a postmodern architectural scholar, Pieris’s approach is evidently different. Grounded in material culture her study unearths the identity dilemmas and crises faced by the ‘1940s-1950s generation’, friends, colleagues and clients of Gunasekara overtaken by a new generation of professionals and intellectuals more akin with the nationalist spirit of the day and at odds with a rebellious youth, product of a monolingual education. Popular memories of the 1970s remain. For today’s urbanized middle classes who grew up or came of age during those years, the 1970s bring back memories of frugal times - import control, queues for bread, eggs and textiles – and often bitter recollections of a time of scarcities. But were these perceptions only those of a few suffering from an austerity with which they were unaccustomed? The book under review which looks chiefly at the middle-classes, therefore acts as a reminder to scholars to begin digging boreholes into the daily lives of the common people as well and look afresh at the elements, the strata, the tensions and the pressures we find there. The past, wrote Lefort, is not really the past until it ceases to haunt us and we have become free to rediscover it in the spirit of curiosity. Anoma Pieris does precisely this when she casts her postcolonial lens on the fate of the middle classes in the 1960s and 1970s and their engagement with issues of space and identity. While her focus is on the place of modernism in architecture through the career of one of its most talented representatives, Valentine Gunasekara, her canvas is in fact much larger. She writes with authority and elegance on the social and institutional frameworks that ultimately marginalized modernism in Sri Lanka and led to the triumph of tropical regionalism epitomized by the works of Geoffrey Bawa. Her book, as the title indicates, shies away from the middle term that generally occupies economic and political analyses and brilliantly encompasses both the meta-narrative of modernity and the detail (Gunasekara’s life choices) to uncover the dynamic bases of architecture. For historians interested in the material culture of societies, materialized manifestations of societies always seem more revealing and enduring descriptors of their attributes and tensions than the ephemera of properly ‘political’ analysis. In this vein Pieris’ sharp analysis of the industrial exhibition of 1965 sheds light on the profound social and political changes that were taking place during those years. The exhibition where Russia and China took pride of place was a site of a divisive cold war alliances and underscored Ceylon’s ultimate bid for non-aligned status. It opened up a decade of social and ethnic strife consequent upon the Sinhala. Only legislation and a gradual marginalization of non-Sinhala Buddhist political and cultural voices and spaces. While Bawa responded to the growing ethnocentric agenda of the state by borrowing from both feudal and colonial vernacular traditions, Gunasekara maintained a fierce alliance with modernism. His client base was after all young men and women who ‘were among the first generation to be educated at the new university of Peradeniya, home grown intellectuals who embraced modernity in the post-independence years’. Interestingly this group rejected both the colonial legacy of the Victorian picturesque and the ideas and values of the rural majority. They did not want to live in anything that resembled a ‘walauwa’ or a British home but instead yearned for the modernity of transatlantic designs. In 1965 Gunasekara and his wife Ranee travelled to the USA on a Rockefeller travel grant. The experience of meeting with architects from Princeton to California changed his approach to architecture. He was particularly impressed with the work and personality of Louis Kahn who was involved in designing the Assembly building in Dhaka. He was also introduced to systematic design and the pre-fabricated kit, quite a different approach from the labour intensive practices that still prevailed in Ceylon. The trip to the USA deeply influenced his designs and methods that quite early reflected and reinscribed his own values which were those of egalitarianism, modern aspirations and religious faith (Catholicism). This book reveals how identity politics provoked an identity driven architecture and demonstrates how architecture like other creative forms mirrors and reflects social and class tensions of a period. The 1960s in Ceylon/Sri Lanka were the site of ‘anti modernist vernacular sensibilities and regionalist representation during the postcolonial period’ (p.7). The next decade reoriented Sri Lankan architecture toward sustainability. Pieris explains that the country then abandoned the modernist aesthetic for a strong regionalist vocabulary based on a postmodern form of eclectism. But it was a warped type of postmodernity which did not rely on the transient and fleeting but instead attempted to recapture authenticity through pastiche and allusion. Initially this approach was confined to a small westernized elite and beyond the imaginaire of the rest of the people caught up in a nationalist fervour; later, however, when applied to public buildings such as the Ruhuna campus and Parliament it gained wider acceptance. Nostalgia was here to stay. By the 1970s it seems that the tastes of a middle-class that had espoused modernism were gradually being reshaped by a hegemonic state. Modernism had only a few defenders and the L shape house was the answer to scarcity. Gunasekara‘s position was further undermined by global events. The oil crisis of 1973 led Sri Lanka and other South Asian governments to shift to an economic strategy of import substitution. This was particularly damaging for Gunasekara who saw concrete as offering opportunities to shape a new architectural expression. The import of structural steel and cement was severely curtailed and led to a halt on new technologies, materials and private enterprise in the industrial sector. Instead the stage was set for a contemporary interpretation of vernacular architecture with its basis in local technologies and materials. In Sri Lanka society was more and more polarized along ethnic lines, and values such as secularism, and universality were considered anti-national. Pieris argues that the demise of Gunasekara and his marginalization mirror the sidelining and eclipse of Westernized middle class lifestyles and values and their final defeat before the more powerful forces of nationalism. Pieris’s argument while sound needs to be nuanced and sometimes tempered. She describes in this book a small group of westernized men and women who opted for modernism and were later displaced by the forces of nationalism. The generation of the 1940s-1950s or what she calls ‘a narrow social group that was forming between the colonial elite and the rural populations’ had, within it a number of different streams, a feature that does not sufficiently appear in this otherwise deeply thought out book. Although Pieris herself acknowledges that members of this middle-class ‘poised between East and West appropriated the trappings of modernity but kept their familial and religious values intact’ she is in fact limiting her narration to the demise of the Christian/Catholic middle classes. Pieris might have distinguished them from the Westernized Buddhists whose defeat was not total since they were closer to the Bengali middle classes of the pre-independence period whose strategy Partha Chatterjee described as encouraging the westernization of the ‘material sphere’ while protecting the ‘spiritual sphere’. They were similarly different from the westernized classes of pre-independence Sri Lanka who called ‘England home’, mimicked the west and were derisively called the Brahmin class by Martin Wickremasinghe. Coincidentally Martin Wickremasinghe’s youngest son’s house in Nawala was designed by none other than Gunasekara. What some of the members of the middle-classes in the 1960s and 1970s aspired to then, was an alternative modernity, a vernacular modernity as it were which was not necessarily parochial or culturally exclusive. Among the westernized middle-classes, men and women made different moves, adopting what may appear to be irrational choices - modernism in their homes and exclusive cultural politics in the public sphere - or modernism in the home coupled with non-sectarian political values. It is these nuances that I missed most in Pieris’s work which otherwise has few unsubstantiated moments. This book has indeed many riches and the reader can ‘poach’ to use de Certeau’s expression whatever he/she is most interested in. It is composed of six discrete chapters. The first chapter, Modernity and Technology contextualizes the professional development of Gunasekara through Ceylon’s Industrial Exhibition of 1965 - a turning point that charted the beginning of a more socialist orientation in building. The second chapter Redefining Home discusses the influence of American postwar housing design on an emerging Asian middle class who had rejected the colonial bungalow and were seeking new forms of social self-fashioning. The author grapples with the notion of vernacular cosmopolitanism imagined by rural migrants into metropolitan areas. Her fourth chapter, Interpreting Community, discusses how a minority Catholic religious community in a predominantly Buddhist country addressed the national climate of the post-independence period through a reformation of church architecture. Her fourth chapter examines the building type that was produced and transformed by the regionalist discourse and publication culture: the resort hotel. Anoma Pieris contrasts the commodification of the resort for western consumption that swept through most creations of the tropical regional schools and contrasts them with V.K Gunasekara’s own efforts at hotel design. Valentine Gunasekara refused to idealize the past and instead designed for the future. He rebelled against the nostalgic trend that revived a vernacular borrowed from both the indigenous and colonial past. In that sense Pieris - who critiques the manner in which regionalism has succumbed to the universal forms of globalization - is clearly sympathetic to his project. But although she writes about Gunasekara with affection and empathy she never eulogises his work or persona. Her book is an attempt at understanding his oeuvre and appreciating the difficult choices he made. Persons interested in architecture and modernism as well as social scientists and discerning readers will appreciate the quality of the writing and the subtlety of argument in this beautifully crafted book. |

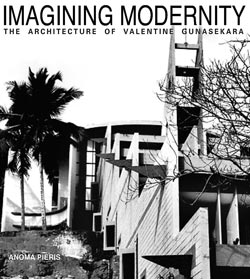

|| Front

Page | News | Editorial | Columns | Sports | Plus | Financial

Times | International | Mirror | TV

Times | Funday

Times || |

| |

Copyright

2007 Wijeya

Newspapers Ltd.Colombo. Sri Lanka. |