Since the birth of the 20 anacondas at the Dehiwela Zoo there has been an extraordinary flow of newspaper reports on the subject. With it has come references to the possible derivation of the name anaconda from the Sinhala henakandaya — garnered from Webster’s and elsewhere - but no proper explanation.

Readers with good memories may remember I wrote an extended article on the subject published in The Sunday Times of June 25, and July 2 & 9, 2000, and those who possess my book Sindbad in Serendib (2008) will have access to that article in chapter-form. The first reference to the name anaconda in English is by R. Edwin (probably a pseudonym) in a letter to the Scots magazine concerning an encounter with a tiger-devouring serpent in then Dutch-held Ceylon. This was published in the 1768 issue under the discursive heading, “Description of the ANACONDA, a monstrous species of serpent. In a letter from an English gentleman, many years resident in the island of Ceylon, in the East Indies.” (See Sindbad in Serendib for the contents of this fascinating letter.)

|

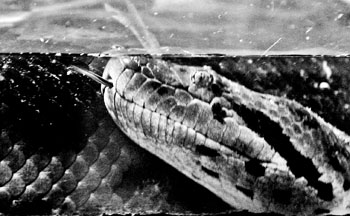

| The adult Anaconda who recently gave birth to 20 anacondas at the Dehiwela Zoo. Pic by Sanka Vidanagama |

The incident recounted, which occurs on the outskirts of Colombo, is a figment of the imagination, full of the popular misconceptions regarding constrictors in an age of limited scientific knowledge of snakes.

There is, for instance, the supposed ability to hang from high branches by the tail, first disseminated by Pliny many centuries earlier when describing African pythons.

Then there is the anchorage of the tail to the trunk of a tree during constriction and eating. Many writers of the time state such anchorage is a prerequisite for constriction or consumption of prey. This is not generally the case, although I’m told pythons occasionally exhibit such behaviour.

Edwin’s most imaginative description is how the snake drags the tiger to a tree and then proceeds to wind itself round both its victim and the tree in order to crush the victim’s bones. The loud cracking of bones during constriction is another common misconception, along with the slavering and vacuuming mentioned.

Its veracity accepted, Edwin’s account became popular after 1768. Thus the myth of the Anaconda of Ceylon evolved. The 1796 Encyclopaedia Britannica based its entry concerning the anaconda on the account. In 1808 it was reprinted, without crediting Edwin, in the Lady’s Museum Monthly as “An Account of the Anocondo, a Monstrous Serpent in the East Indies, and of the Manner of its Seizing and Managing its Prey”. It was also turned into a short story, “The Anaconda”, by ‘Monk’ Lewis, in Romantic Tales (1808).

That the myth of the Anaconda of Ceylon had taken firm root is evident from the works of early and mid-nineteenth century English writers. Robert Percival remarks in An Account of the Island of Ceylon (1803): “I had heard many stories of a monstrous snake, so vast in size as to be able to devour tigers and buffaloes, and so daring as even to attack the elephant. I made every inquiry on the spot concerning this terrible animal, but not one of the natives had ever heard of the monster. Probably these fantastic stories took their rise from an exaggerated account of the rock-snake (python).”

James Emerson Tennent writes in Ceylon (1859) of “the great Python, which is supposed to crush the bones of the elephant, and to swallow the tiger”. (The use of the name tiger in relation to Sri Lanka is not in error, for prior to the late-nineteenth century the country’s larger cat species were referred to by this name.)

These authors probably knew of Edwin’s account. Others mention the name anaconda in relation to the python. J.W. Bennett, in Ceylon and its Capabilities (1843), gives a list of the Sinhala names of thirty-one snakes found in the island, number twelve being “the Pimbera and Anaconda”. He adds: “The Pimbera or rock snake, is said to be the Anaconda or Anacondia of ancient writers.” (Pimbura is the Sinhala for python, from pimb-, to hiss or blow.)

Henry Charles Sirr notes in Ceylon and the Cingalese (1850): “The largest of the serpent tribe in Ceylon is the anaconda (belonging to the genus Python) and is far from being uncommon in the island.”

These accounts suggest the Anaconda of Ceylon is nothing other than the python. It will be recalled, though, that many dictionaries advance the hypothesis that it is a snake called the henakandaya from whose Sinhala name anaconda is derived.

But physically the henakandaya is in complete contrast to the anaconda. It is the colloquial name given to the Brown Vine Snake (Ahaetulla pulverulenta), which grows to a maximum length of five feet and has a very slender body, large eyes, and long snout. An arboreal species, it eats lizards, frogs, toads and similar prey.

According to P.E.P. Deraniyagala in A Coloured Atlas of Some of the Vertebrates From Ceylon, Volume Three (1955): “Although the Brown Speckled Whip-snake (Brown Vine Snake) is only mildly venomous, its bite is believed by the Sinhalese to be so virulent that it paralyses victims and causes them to wither up as if struck by lightning.” Hence this snake is known as the henakandaya - a compound of the Sinhala for “lightning” and “stem” or “trunk” (-ya being the masculine nominal termination). Some suggest that “thunderbolt snake” is a fair translation.

The most comprehensive entry regarding anaconda is not, as might be expected, in the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) or Webster’s. Instead it can be found in the little-known Hobson-Jobson: A Glossary of Colloquial Anglo-Indian Words and Phrases (1886). The compilers, Henry Yule and A.C. Burnell, carried out the initial investigation into the derivation of anaconda. Indeed, most dictionary derivations of the word, especially the one in the OED, have relied almost exclusively on their findings.

The opening sentence of the entry for anaconda in Hobson-Jobson sets the tone of any inquiry into the word’s history. “This word is of very obscure origin,” the compilers caution readers.

Originally, they supposed the name to be of South American origin. However, a trawl through antiquarian books drew a blank. In South America, with its multifarious languages and dialects, there are many names for the anaconda, the main being sucuriu or sucuriuba.

Having disposed of the idea of a South American derivation, Yule and Burnell reveal: “The oldest authority that we have met with, the famous John Ray (referred to as the father of English natural history) distinctly assigns the name, and the serpent to which the name properly belonged, to Ceylon. This occurs in his Synopsis Methodica Animalium Quadrupedum et Serpentini Generis (1693). In this he gives a Catalogue of Indian Serpents from the Leyden Museum (Holland).”

The catalogue was transcribed at Leyden by a physician, and Ray reports that No.8 on the list reads in Latin: “Anacondaia Zeylonensibus, id est Bubalorum aliorumque jumentorum membra conterens” - “the anacondaia of the Ceylonese, i.e. he that crushes the limbs of buffaloes and yoke beasts”).

Having found no discernible Sinhala connection, Yule and Burnell suggested a Tamil interpretation, “anai-kondra (anaik-konda), ‘which killed an elephant’”. As already discovered, both Percival (1803) and Tennent (1859) claim that pythons overcome not only tigers and buffaloes but elephants as well. Furthermore, in the adventures of Sindbad the Sailor, the King of Serendib entrusts Sindbad with the task of conveying, among other things, an enormous snakeskin of “the serpent that swalloweth the elephant” to the Caliph of Baghdad.

During their research, Yule and Burnell discovered that Edwin’s account contained the earliest reference to the word in English. In their entry they put forward a convincing argument regarding the origins of Edwin’s account: “The whole thing is very cleverly told, but it is evidently a romance founded on the description by D. Cleyerus (of a Reticulated Python of the Dutch East Indies) which is quoted by Ray.”

Indeed, Edwin’s description of the snake’s method of constriction is almost identical to Cleyerus’: “How, if the resistance is great, the victim is dragged to a tree, and compressed against it; how the noise of the crushing bones is heard as far as a cannon: how the crushed carcass is covered with saliva, etc.”

Yule and Burnell believed that Edwin was a Dutch surgeon serving in the Royal Navy and that he was also responsible for another such yarn concerning the poisonous Upas tree of Java.

It was Donald Ferguson, the Ceylon-based antiquarian researcher, who suggested anaconda was derived from henakandaya. His hypothesis is contained in the Oxford-based Notes and Queries, August 14, 1897, headed “The Derivation of ‘Anaconda’”.

In Leyden Museum catalogues of 1697 and 1698 Ferguson found three titles:

Hoenacandaja/Hanacandaja/Henacandaja Zeylonensibus”. He comments: “It is evident that the form anacondaia is due to an error” (in transcription by Ray’s helper: a classic example of how research can become derailed). “With the restoration of the initial h, and the correction of hoena- and hana- to hena-, the origin of the word is at once revealed. It is simply henakandaya, the Sinhalese name for the whip-snake (brown vine snake).”

The last piece of the puzzle, why the colloquial name for a small vine snake of Sri Lanka was transferred to a large constrictor of South America, is provided by the OED entry. This is the revelation that the French naturalist, François-Marie Daudin, appears to have either wrongly identified a specimen or its source. In naming the large South American water snake Boa anaconda, it seems that he, rather than the Portuguese, was responsible for the transportation of the name across continents during the early years of the nineteenth century.

Richard Boyle is the Sri Lankan English consultant to the Oxford English

Dictionary |