It is hardly visible to the naked eye - tinier than a mosquito. Known as the ho-haputuwa or weli-messa in local parlance, the sandfly is the vector that transmits the leishmaniases parasite which looks like "a dash and a dot" when put under the microscope.

|

| The magnified sandfly |

This is the parasite when injected into the blood of mammals including human beings causes the tongue-twisting disease - leishmaniases. "It seems to be an established disease," says Prof. Nadira Karunaweera, Head of the Department of Parasitology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Colombo, explaining that although there are over 20 species of the parasite, the one identified in Sri Lanka is Leishmaniases donovani.

Very similar to the Indian strain, there is only a slight mutation in the local parasite, MediScene understands.

What happens when, through the infected bite of a sandfly (see box), the parasite gets into a human's blood?

The parasite multiplies in mono-nuclear cells, reaches maturity and then ruptures, entering new cells and multiplying until treatment stems the cycle. It replicates within the macrophage (a large cell that is able to remove harmful substances from the body and is found in blood and tissue), ultimately leading to disease manifestations.

Depending on the species of the parasite and other factors (such as immunity and genetics) with regard to the host, the disease could take three forms:

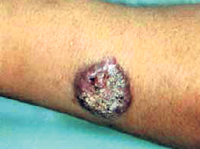

- Cutaneous form - Lesions, if untreated, followed by skin ulcers on the exposed parts of the body such as the arms, legs and face and also in men who work outdoors bare-bodied on the back of the chest and abdomen, which would be the areas to get a bite of the sandfly.

- Mucocutaneous form - If the bite is near the mouth and nose, the lesions could spread to the mucosa in those areas and cause partial or total destruction of the mucous membrane and surrounding tissue, especially cartilage, leading to disfigurement.

- Visceral form - This is the most dangerous form of the disease which could affect organs such as the liver and the spleen, leading to death unless detected early and treated effectively.

In Sri Lanka, the common form is cutaneous, while only three cases of the more dangerous visceral form have been detected in 2007, stresses Prof. Karunaweera.

Worldwide more than 350 million people in over 88 countries are at risk of contracting leishmaniases, MediScene understands, with around 1.5-2 million new cases occurring per year. More than 150,000 new cases of the cutaneous form which has a higher prevalence in countries facing civil wars such as Afghanistan and Sudan are reported per year.

Dealing with the Sri Lankan situation, Prof. Karunaweera said that when the first local case was reported in 1992 from Ambalantota, it was considered an "imported" disease. However, the picture began changing in 2001, when there was an influx of patients with symptoms suggestive of leishmaniases. "We saw the parasite in the lesions."

So far around 1,500 patients with leishmaniases have been referred to the Department of Parasitology from different parts of the country, mainly Matara, Hambantota and Anura-dhapura. "But this is not a true reflection of the disease numbers," says Prof. Karunaweera, adding that patients may be receiving treatment elsewhere and returning home.

The skin lesion is non-tender or does not hurt and is non-itchy, so people may not even realize that they have leishmaniases, she says, explaining that it could go on from about one month to several years before patients seek treatment.

It could be just one lesion or multiple lesions depending on whether it is a single sandfly bite or multiple bites while the lesions could also appear as scaling nodules. Later they could develop into ulcers which would have a raised edge and depressed centre, she says.

Who is vulnerable?

A common factor in this disease is that those affected have been outdoors, as workers or even those living close to the jungle.

Urging more public awareness with regard to this treatable disease, Prof. Karunaweera says it is of vital importance to keep proper records of patients, get laboratory confirmation on the diagnosis of leishmaniases and ensure access to treatment for those infected. "To ward off the disease, people can use an insect repellent, cover exposed areas of the body and sleep under insecticide-impregnated bed nets."

Stressing the need for more work in this area, Prof. Karunaweera says so far the parasite has been found in the reservoir host who is the human. The challenge now is to isolate the parasite within the vector, the sandfly, itself and also identify the other mammalian hosts, if any, which could also act as reservoirs of infection.

Deadly female who lurks in the dark

Hiding in mud walls, abandoned buildings and store-rooms, the local insect-vector, the phlebotomine sandfly (one among 30 species) is only about 2-3 mm in length. This inconspicuous insect is a quiet-flyer with weak wings, having a limited flight range.

Preferring moist, dark places during the day, it mainly hops around. Deadlier than the male as in mosquitoes, it is the female which comes out from its hiding place in the evening and night, looking for a blood-meal from an unsuspecting human or other mammal.

Notifiable disease

Giving due priority to prevention and also timely treatment, the Ministry of Health has declared leishmaniases a "notifiable disease" while appointing a Technical Advisory Group to come up with an action plan.

The high-level group headed by Dr. Sunil Settinayake, Director of the Anti-Leprosy Campaign, will develop a strategy on prevention and treatment.

Meanwhile, a major 'Symposium on Leishmaniases' with both foreign and local experts will be held on February 1, next year, for researchers and health-care personnel.

The symposium will be a joint activity between the Faculty of Medicine, University of Colombo, the Ministry of Health and the National Science Foundation of Sri Lanka which will be the main sponsor.

|