The big yellow bus from Trincomalee is going where few buses from Trincomalee dare to venture. As it groans its way up the narrow, twisting hill-country roads towards Kandy and Nuwara Eliya, the silence inside the bus is pregnant with tension. Neighbours– men and women from the Ecchalampattu area of Trincomalee –avoid speaking to each other.

The forty-odd farmers inside the bus have been selected from neighbouring Sinhala and Tamil communities in Echchalampattu for this once-in-a-lifetime trip to Kandy. Despite being neighbours, the farmers normally cleave to their respective communities, and there is little if any interaction between them. Language and cultural barriers, sharpened by the decades-long civil conflict have conspired to keep these communities apart.

Ostensibly, this is a business trip. All of them are dairy farmers, and all struggle with the low milk yields provided by their Indian breed of cow and the arid climate. This trip to Kandy and Nuwara Eliya, the fertile heartland of the country, will expose them to improved farming practices. On a deeper level, this trip also intends to break down barriers between the communities. Many of the farmers have never been outside the Eastern Province before; and now, here they are, travelling some 160 kilometres with each other in a big yellow bus. Mutual suspicion has divided the bus into ‘Sinhala’ and ‘Tamil’ halves; both sides stare out of their respective windows and refuse to make eye contact or smile. Selina, the programme manager from the NGO that is sponsoring the trip, struggles to break the silence.

|

| Putting their heads together: A peace building activity in progress. |

Dairy farming, largely the domain of small-scale enterprises, has perhaps been most successful in the relatively cool environs of the central highlands of Kandy and Nuwara Eliya. By contrast, much of the north-east is dry and dusty when it is not monsoon season, and farmers struggle to feed and water their animals. The conflict has also contributed to the difficulties of farming, pock-marking the countryside with remnants of warfare and scattering herds widely. Traditionally, most farmers are used to only squeezing out enough milk to feed their families; surplus milk, if any, either spoils or is sold to middle-men who then sell it on to the big dairy corporations.

MILCO (Milk Industries of Lanka Co Ltd) the government’s dairy body has been working with various NGOs to set up Farmer Managed Societies (FMS) around the country. Dairy farmers can drop off their daily collection of milk at a nearby FMS to get it analysed for fat content and non-fat milk solids.

The milk is then chilled before being transported to more central milk-processing centres. In this way, dairy farmers can cut out the middle-men and deliver their milk directly to MILCO, resulting in a higher profit margin for themselves. Also, as most of the milk-processing factories are located in the highlands, farmers in Trincomalee are provided with a storage service for their milk until it can be transported.

The traditional dairy cow in Sri Lanka is the lean brown Indian variety – bred for its toughness in arid climates such as north-east Sri Lanka, it is nonetheless a poor producer of milk (on average only 1 litre a day). Breeding programmes have been instigated that cross-breed these Indian cows with their fatter, more productive European brethren –Jerseys and Herefords– in order to produce hybrid cows that can provide up to 10 litres of milk a day.

Thus there is much hope that this trip will be highly educational, and encourage the farmers to follow improved agricultural practices. However, so far the trip appears to be going badly.

The unease in unfamiliar surroundings contributes to the strained silence inside the bus; nobody is willing to break the ice and make the first move.

And then, on the Dambulla-Matale road about 7 km out of Dambulla, a car full of youths collides with the bus. They jump out of their car and begin yelling at the bus, demanding to know why a Tamil bus is in ‘their’ area.

This collision – not an uncommon occurrence in the traffic chaos– then inexplicably becomes the catalyst for one of those rare moments of human grace and solidarity that leave goosebumps on your skin. For the Sinhalese farmers on the bus, seeing the fear on the faces of their Tamil counterparts, tell the latter to stay put, and descend from the bus to give the youths an earful. This is NOT a ‘Tamil’ bus, they say; this is a bus from Trincomalee. The people on this bus are from Trincomalee, they are all farmers, and they all have a perfectly valid reason for being on this educational business trip. And furthermore, the accident was most definitely not the bus driver’s fault; why was the car being driven so recklessly? The youths, chastened and embarrassed, slouch off and the atmosphere of icy indifference on the bus is replaced suddenly by beaming smiles all around.

The rest of the week is spent in much excited chatter. Most of the Tamil farmers can speak and understand Sinhala, but few of their counterparts are fluent in Tamil. Nonetheless, the farmers animatedly use their hands and eyes and arms and smiles to reach out to each other. Selina, who is fluent in Tamil, Sinhala and English, almost cannot keep up with the demand for her interpretation services. Some of the women share a dormitory room whilst in the Kandy hostel; an action that would have been unthinkable to them just a week ago. All round, they catch glimmers in each other of their common humanity; of fragile shared hopes for a better life, of cherished dreams of family and friends, of common worries about their next meal or the family’s livelihood. They realise with a start just how much like each other they are.

The week’s programme unfolds smoothly. First up are visits to several farms – including the CIC Agricultural farm in Dambulla and the Digana factory owned by MILCO (at this last farm, they watch in fascination as huge vats of milk are pasteurised and then churned into butter, yoghurt and ice cream. The smell of warm milk is pervasive and takes us back to nursery days, and everybody tucks in with relish to their free pottle of creamy yoghurt). There is a visit to a Farmer Managed Society in Hatton, where there is much discussion of the differences inherent in dairy farming between the relatively peaceful and green pastures of Nuwara Eliya, and the sometimes dry and barren grazing-lands of the North-east. At the NLDB Training Centre in Digana, the farmers are instructed on cattle management and improved agricultural practices; there is much combined hilarity as the cows, who have never been creatures to appreciate the solemnity of any occasion, frequently splash those nearby with unheralded streams of urine or worse.

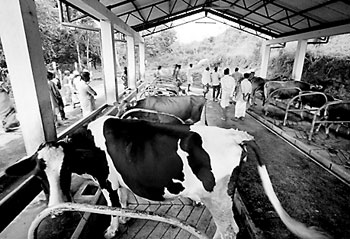

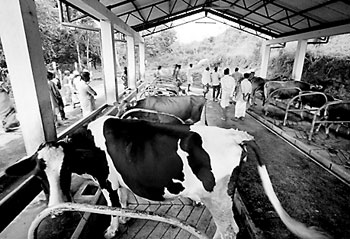

|

| Part of the programme: Visiting a farm |

A particularly important focus of the week are the lectures and peace-building activities run by the Human Rights Commission. Tellingly, when the farmers are asked if they have a right to life, many answer ‘no’ – and they answer truthfully, not in sarcasm, for this is what they have come to believe. This is a common viewpoint. At the end of the sessions, they have learnt that in fact they do have fundamental rights under universal humanitarian laws. The bonding that began with the bus accident is formalised and cemented as they take part in games and activities designed to make them appreciate the commonalities between their communities.

Of course, there are plenty of social activities too- a visit to the Dalada Maligawa, or the Temple of the Tooth in Kandy and also to the Kathiresan Hindu temple. One night, a troupe of performers arrives at the hostel where the group is staying, and performs for the crowd – swallowing large tongues of flame, walking on hot coals to the hypnotic beat of traditional drums, leaping and dancing.

At the end of a full week, the big yellow bus slowly descends from the cool hills of Kandy, shrouded in mist, to the flat alluvial expanses of north-eastern Sri Lanka. The farmers have made friendships with each other that they vow to continue in the future. No longer will they ignore the neighbour who lives but a kilometre from them, in the mistaken assumption that they cannot possibly have anything in common with those of another race. A Sinhalese woman farmer has tears in her eyes as she hugs her new Tamil friend good-bye; both have been overwhelmed by the boundaries that have been crossed on this trip. |