What follows is not a review of Tamil Tigress (hereafter, TT) but an attempt to use it to raise and share some questions about issues such as writing, veracity and the “reception” of a text. The word “text” signifies “that which is woven” and suggests the coming together of different strands to form a composite, a whole, with its own shape and design, as in a carpet. “Context”, made up of “con” (or “with”) plus “text”, is that which surrounds and accompanies a text.

The author has adopted the pseudonym, Niromi de Soyza, in honour of Richard de Zoysa, poet (see, Sarvan, Sri Lanka: Literary Essays and Sketches, 2011) and political activist; a man of principle and vision, tragically murdered at an early age. The author has adopted the pseudonym, Niromi de Soyza, in honour of Richard de Zoysa, poet (see, Sarvan, Sri Lanka: Literary Essays and Sketches, 2011) and political activist; a man of principle and vision, tragically murdered at an early age.

Niromi de Soyza, born in Kandy to a Jaffna-Tamil, Christian, father and an upcountry Hindu Tamil mother, was sent to Jaffna when she was nine to stay with her paternal grandmother. Her mother and younger sister followed a few months later. Soyza states she joined the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) in 1987 when she was nearing seventeen, and was with them for nearly a year. (TT is dedicated to “The ones I loved and lost”.) She left the movement in 1988, continued her secondary education in India, and later moved to Sydney. TT purports to be the memoir of that one year.

However, Michael Roberts, Arun Ambalavanar (also known by his pen-name, Nadchathran Chev-Inthiyan, a Tamil poet now living in Australia) and others have questioned the veracity of TT. The mistakes are so many and blatant as to be “laughable”: contrary to what the text states, The University of Jaffna does not have an Engineering faculty. The senior Tiger leader Bashir Kaka was not a Muslim but a Hindu: Bashir Kaka was his nom de guerre. The name of the murdered principal of St John’s College was Anandarajah and not Anandarajan. Soyza sprinkles the narrative with obscenities which are not common Jaffna expletives.

The equivalent of “boyfriend” did not exist in Tamil in the mid-eighties because both Jaffna society and the LTTE were “puritanical”. Sri Lankans are unlikely to describe arrack as “the local beer”. Perhaps, the last three verbal substitutions (all familiar to Westerners) indicate the intended readership? In contrast to mistakes, I came upon the following in connection with the Ben Bavinck diaries: TT is correct about the random bombing and shelling to which the Jaffna Peninsula was subjected to in the mid-1980s. So it is not a simple matter of “all true” or “total fabrication”, though it can be argued that the most persuasive lies are those which include (to varying degree) elements of truth. Further, scientists have shown us that mental recall is not to be implicitly relied upon: we may “remember” an incident (or detail) that never really happened. So inaccuracy need not necessarily mean duplicity.

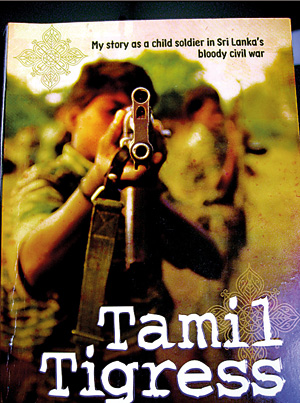

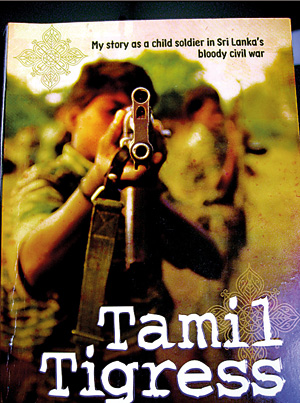

A Sri Lankan friend (author and journalist now settled in Australia) thinks the book was “manufactured” with an eye to the commercial profit that sensationalism (title: Tamil Tigress; subtitle: “child soldier”, “Sri Lanka’s bloody civil war”) garners. If so, there are precedents. James Macpherson’s much-acclaimed ‘Ossian’ (1760s) was challenged both on literary and political grounds. Dr. Johnson dismissed Macpherson as a mountebank, liar and fraud. (I thank Liebetraut Sarvan for reminding me of this episode.

The debate continues, though in attenuated form.) In the 20th century, the German magazine ‘Stern’ commissioned Hugh Trevor-Roper to examine the then-recently “discovered” diaries of Hitler. Trevor-Roper is author, among other works, of the bestselling ‘The Last Days of Hitler’. Master of Peterhouse, Cambridge; Oxford Professor of History, he was elevated Baron Dacre of Glanton in recognition of his distinguished contribution to History and the nation. The eminent authority examined and authenticated the diaries; ‘Stern’ paid ten million Marks, secured rights and, in April 1983, published the diaries. They were forgeries, a complete fake. Two editors of ‘Stern’ resigned, as did the editors of ‘The Sunday Times’ and ‘Newsweek’ magazine. Damage to reputation and financial loss were considerable.

In Literature, a taxonomic division is that into Poetry, Drama and Fiction.

(The last is separated into the novel, the novella and the short story.) But there’s also the ‘Fiction’ / ‘Non-fiction’ dichotomy which reminds us that “fiction” can mean “lies”: writers tell lies, in that they invent character and action, and give the former thoughts and words. But, as it has been said, writers tell lies in order to tell truths - about human nature, experience and relationships; society, government and the state. We all are familiar with stories (some in the realm of fantasy) which solemnly state at the beginning that what follows is a true record. We read, enjoy (and perhaps profit from) such a work, knowing full well that it’s imaginative, and not factual, be it in the form of a diary or a memoir. There’s factual truth, and the truth of the imagination. In German, certain stories are known as “Lügengeschichten”. “(Lügen” means lies; “Geschichten”, stories.)

We also encounter works, ostensibly fictional, but which we recognise as being heavily biographical or autobiographical: it is the opposite of fiction masquerading as fact. Carl Muller’s Burgher novels – superficially hilarious and ribald; sad at a deeper level – come to mind. The legal protection of the disclaimer “Any resemblance to persons living or dead” etc comes to mind. Films depicting the historical past – its setting, characters and events – take liberty, often leaving some members of the audience with the belief that they had seen was based on fact.

Another aspect is the character of the writer. Again, we all can summon up examples of writers (creative or scholarly) of whose morals - or lack of them - society thoroughly disapproved and yet who produced outstanding work. Are we to condemn “good” (great, original, outstanding) work because the writer is considered “bad”? The same applies to the work of artists, film producers, scientists, philosophers and academics. And, one may ask, what of politicians?

Michael Ondaatje observed that in “Sri Lanka, a well-told lie is worth a thousand facts” but it is so the world over, and if de Soyza had described her work as a fictional memoir, mistakes would have been pointed out but the work would not have provoked opprobrium and obloquy. When reading a fantastic story that makes-believe it’s true, we enter into a convention, willingly and temporarily suspending our “disbelief” – as we do with aria sung in opera while murder is being perpetrated. The first-person narrative is another example. At random, ‘Moll Flanders’, ‘Gulliver’s Travels’ and ‘Heart of Darkness’ come to mind, not to mention Aravind Adiga’s ‘White Tiger’, Romesh Gunesekera’s ‘Reef’ and Elmo Jayawardena’s Sam’s Story. Verisimilitude, after all, functions within a convention.

The present reception of TT has to do with the seriously meant claim of real (and not imaginary) truth. Choosing to come under the classification of Non-fiction, it is reacted to, and evaluated, on its own claims. Our response has much to do with our recognition and acceptance of form. For example, “Who would I show it to” is unremarkable - though one may notice the absence of the final question-mark. But given the title ‘Elegy’ and appearing in a poetry anthology, it becomes a poem - and a deeply moving one at that. W. S. Merwin’s, the one-line poem has had paragraphs and pages written on it. (As a one-time teacher of English literature, I know something of the different interpretation and response the poem evokes.)

It is said, “Even [great] Homer nods”, makes mistakes. What creates great literature is not the absence of flaws but the presence of certain other qualities. All fiction (fantasy, science fiction, fairy stories included) is based, to varying degree, on fact and reality. What if de Soyza had presented TT as fiction based either on personal experience or research? Inaccuracy would have been noted but there would not have been (as with some readers at present) anger at (alleged) despicable deceit and attempted fraud. Claiming the work is based on fact and directly lived experience, makes truth a primary pillar, and when that pillar of veracity is shaken, the book falls. What is inaccurate or false in detail may come to damage, if not destroy, the essential, and far more important, truth of experience and insight.

Each reader must, and will, judge for herself / himself whether TT is a lie and, if so, a well-told lie (Ondaatje). Further, it is now a commonplace that there is no innocent text: ideology is inevitably and inescapably inscribed. No doubt, TT will be “interrogated” and reacted to by each reader through the spectacles of his or her own ideology. |

The author has adopted the pseudonym, Niromi de Soyza, in honour of Richard de Zoysa, poet (see, Sarvan, Sri Lanka: Literary Essays and Sketches, 2011) and political activist; a man of principle and vision, tragically murdered at an early age.

The author has adopted the pseudonym, Niromi de Soyza, in honour of Richard de Zoysa, poet (see, Sarvan, Sri Lanka: Literary Essays and Sketches, 2011) and political activist; a man of principle and vision, tragically murdered at an early age.