The economic reforms introduced in November 1977 were a sharp break from the previous economic regime. The new policies transformed a closed, tightly-controlled inward looking economy pursued from 1970 to 1977 into a market-oriented, outward looking one.

The government laid greater emphasis on private enterprise. Economic growth was to be achieved through an export-led strategy rather than one on import substitution. Economic liberalisation in 1977 marked a watershed in the country's economic policies.

The political courage to undertake these bold reforms was derived from the failure of the 1970-77 policies to generate economic growth and employment opportunities and the deprivations and hardships people underwent during those years. It sought private foreign investment aggressively under the auspices of the IMF and World Bank and obtained considerable amounts of foreign aid and assistance for investment.

Economic reforms of 1977

The reforms of 1977 were a sharp break from past economic regimes. They included the liberalization of trade and exchange controls and the introduction of an economic strategy dependent on private investment and market forces. Foreign investment was encouraged and a greater reliance was placed on exports.

The Government adopted a unified exchange rate, devalued the rupee and adopted a floating exchange rate. These reforms relied on large-scale support from international agencies, notably the IMF, the World Bank and donor countries. The IMF provided balance of payments support, while the World Bank gave long-term credit for development programmes and arranged donor assistance through the annual Aid Club meetings.

Foreign assistance was aggressively sought and successfully obtained. Foreign investment was sought by giving investment guarantees and tax concessions. The safety of foreign investment was guaranteed in the new constitution adopted in 1978. The opening of the Free Trade Zone under the Greater Colombo Economic Commission (GCEC) was to encourage foreign direct investment for export industries. An export-led economic strategy was a cornerstone of the new policies.

It was recognised that high rates of economic growth could be achieved only by increasing new industrial exports. Export industries obtained concessions and an export-based policy stance developed. There was an attempt to emulate the NICs: Singapore in particular.

Specific policies

More specifically, the economic liberalization programme replaced quotas by tariffs (with the exception of controls on less than 200 items, such as motor cars, guns, ammunition and aircraft). Tariff rates were reduced on most commodities. Foreign exchange restrictions were drastically modified and the foreign exchange regime liberalized.

Most price controls were removed and barriers to internal trade were abolished and there was a shift away from administered prices and subsidies to market prices. The reduction of subsidies was part of a movement towards a reduced welfare programme, in which universal subsidies were replaced with more targeted ones. The extensive food subsidies programme was curtailed by restricting it to a smaller section of the population through a programme of food stamps.

The policies included an urban renewal programme, the development of economic infrastructure, the establishment of a Free Trade Zone and the implementation of an Accelerated Mahaweli Development Programme that was to increase agricultural production and hydropower generation.

Fiscal policies

The fiscal policy orientation changed drastically. Fiscal policies were used to support the market orientation and private sector emphasis on economic growth and to create a climate conducive to private investment and private economic enterprise. The reduction in taxes and the use of a wide range of tax incentives encouraged investment. Direct taxation became an instrument for resource allocation rather than to mobilise resources for public investment or for income distribution. The emphasis in government expenditure shifted to investment, particularly in infrastructure and large-scale projects like the Accelerated Mahaweli Scheme, rather than on consumption, welfare and social development expenditure.

Privatisation

Privatisation of state enterprises was a key policy of the government. By end 1993, 42 state enterprises had been privatized. Further, most of the state-owned plantations were handed over to 22 companies for management. The two state banks were re-structured to meet the capital adequacy requirements by the infusion of Rs. 24 billion and restrictions on foreign investment in the Colombo Stock Market were removed.

Economic performance

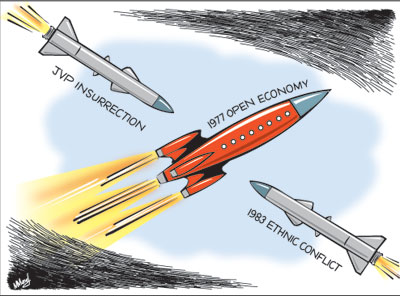

The economic reforms and enhanced foreign funds led to a high rate of economic growth till 1983, when ethnic disturbances resulted in a setback. The economy grew by an annual average of 6 percent in 1978-83. The ethnic disturbances of July 1983 set back the growth thrust in many ways. The boom in tourism was busted, foreign investors who had ideas of establishing industries were turned away and several economic activities such as agriculture and fisheries in the North and East were disrupted. The subsequent terrorist demand for a separate state in the North and East and terrorist attacks undermined business confidence, foreign investment and tourism, besides dislocating agriculture, fisheries and a few industries in the North.

Soon after the arrival of an Indian Peace Keeping Force in the country, an insurgency developed in the South. From 1987 to 1989, this insurgency dislocated work and seriously impaired economic activity. The economic growth rate fell from 4.3 per cent in 1986 to 1.5 per cent in 1987. In 1988-89 growth averaged only 2.5 per cent.

Further reforms in 1989

The weak economic performance in the late 1980s led the government to adopt further structural reforms. The reforms aimed at strengthening budgetary management, reducing inflation and improving the balance of payments and external reserve position which had weakened considerably. The economy was liberalized further after 1989. The tariff structure was simplified and import duties reduced, foreign exchange restrictions on current account transactions were removed and the country accepted IMF's Article viii obligations from March 15, 1994.

In the latter half of 1989 the government depreciated the rupee by about 17 per cent and cut budgetary expenditures by 20 per cent. Central Bank holdings of Treasury Bills were reduced by allowing market interest rates to prevail in the Treasury Bill market and thereby encouraged TBs to be absorbed by the private sector. The tax system was restructured during 1989-93 to eliminate distortions and reduce tax on savings. The maximum rate of corporate tax was reduced to 35 per cent and personal taxation to 40 per cent. A four band customs tariff on imports was introduced with a maximum 50 per cent tariff and export duties on tea, rubber and coconut were progressively reduced and ultimately eliminated.

Structural changes

These economic reforms had a significant impact on the structure of the economy. Export led manufacturing gained in importance progressively and the share of manufacturing in GDP that had declined to 14 per cent by 1977, increased sharply to 20 per cent by 1990, 23 per cent by 1997, and to 27.2 per cent in 2004. The contribution of agriculture to GDP declined to 23.3 per cent by 1990, 19.7 per cent by 2000 and to only 17.9 per cent by 2004. There was a sharp increase in the contribution of the services sector from 40.6 per cent in 1977 to 55.4 per cent 2004.

As much as there were changes in the relative importance of the sectors, there were qualitative changes in them. Before 1977 industrial output consisted of tree crop processing and a few industrial products like cement, chemicals, glass, a large number of small industries producing a wide range of consumer items for the protected domestic market and cottage industries. In the post-1977 period of trade liberalisation and encouragement of foreign investment, there was a significant expansion and diversification of the industrial sector. Unlike in the pre-1978 period private industry became dominant with as much as 96 per cent of industrial production being in the private sector.

Factory industry replaced export crop processing in importance. Small and cottage industry declined. Factory industry now contributes more than about 85 per cent of industrial output, while export crop processing contributes less than 10 per cent and small industry about 4 per cent of total industrial output. Factory industry itself has shown considerable diversification. Despite ready-made garments holding a dominant position by contributing over 50 per cent of industrial output, a wide range of industrial items is produced for export.

These structural changes in the economy reflected in the country's trade pattern. Agricultural exports dominated the export structure from the beginning of the plantation economy till the 1980s. A significant diversification of exports occurred in the 1980s, and by 1989 agricultural exports had declined to about 35 per cent of exports. By 1999 it declined further to 21 per cent and in 2004 it was only 19 per cent. In fact agricultural and industrial exports had exchanged their positions of importance. In 1977 agricultural exports accounted for 79 per cent of exports, in 2004 they accounted for only 19 per cent of exports. In contrast, Industrial exports that were only 14 per cent in 1977 accounted for 78 per cent of exports.

Lessons of the experience

These years provided evidence that an export-led economic strategy was best suited to the country. The economy grew at higher rates and there was a structural transformation of the economy and the export structure changed from dependence on primary agricultural exports to industrial exports. Industries and services contributed a larger share to GDP. The private sector contributed much to the country's economic growth and resilience.

This period also brought out the lesson that internal strife was a serious blow to economic development. There can be no doubt that the development thrust begun by the shift in policies was choked by the ethnic violence, terrorism, and insurgency. Foreign investments that could have spurred economic development were turned away to other countries in Asia such as Malaysia and Singapore. Economic progress of the country for the next three decades received an irreversible set back.

|