3rd December 2000

News/Comment|

Editorial/Opinion| Business| Sports|

Sports Plus| Mirror Magazine

Caption for Picture

- Hard nut to crack

- Meeting through movement

- From old to new, real to unreal

- A loving historical portrayal of a birthplaceBook review

- Help! Bread's gone up again!

- No bitter pill

- Hey, the job is yours - Funny Business

- A little tender loving care to treat your feet

- Guitar dream

- Help them to go to school

- Where lumps turn shapely

- No silver lining

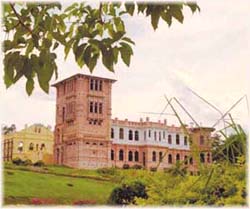

- Kellie's Castle: Fantasy or folly?

- Nari Bena in London

- A vision becomes a reality

- The rent issue

- Letters to the editor

More rural women than men 'succumb' to the allure of cashew, an ideal crop for the dry zone

Hard nut to crack

When

we pop those devilled cadju into our mouths, how many of us think of the

long and arduous process that has brought that tasty dish to us? The plucking

of the raw cashew, the sunning, the shelling, the heating once again and

the peeling are indeed arduous and mostly done by women.

When

we pop those devilled cadju into our mouths, how many of us think of the

long and arduous process that has brought that tasty dish to us? The plucking

of the raw cashew, the sunning, the shelling, the heating once again and

the peeling are indeed arduous and mostly done by women.

Sriyani Prithika is one of the thousands of women scattered around the country involved in this difficult industry. In 1999, 35,000 people, a majority of whom are women, were engaged in the processing of cashew. According to Cashew Corporation estimates 60,000 cashew farming families are part of their subsidy scheme.

We met Sriyani, 28, in Vanathavilluwa, 12 miles from Puttalam. "I own four acres of cadju land. Those days I used to do the shelling of a portion of the raw cadju that we grew at home, but it was time consuming. Sometimes we were compelled to sell the raw cadju to the middlemen, at their prices. But now I get a better deal, because we are workers and also owners of this centre."

Sriyani, mother of two, is referring to the Thammanna Agro Production Company Cashew Processing Unit, for which the Intermediate Technology Development Group (ITDG) provides the technology. It is run on a cooperative basis where the members are owners as well as workers.

"My husband goes on his bicycle selling the produce from our garden such as manioc and banana. I come to the centre, which is very close to my home and work a six or four-day week," she says, continuing with the shelling of cadju, for any delays mean a monetary loss for her. Her role as a worker at the processing centre, shelling about 25 kilos of cadju from around 8 a.m. to about 5 p.m., brings her about Rs. 150 a day.

But shelling cadju is not that easy. Though Vanathavilluwa is in the arid zone, the eight women shelling cadju are wearing long-sleeved, high-necked blouses over their clothes. They are also wearing protective gloves.

"Cadju kiri visai" (The cadju milk is potent), says Nilmini Chrysanthi, 32. If it hits the skin, the skin burns and "wana wenawa" (sores erupt).

She does not earn as much as some of the others as she goes home at noon to cook lunch for her schoolgoing nine and seven-year-old children. So she can shell only about 15 kilos of raw cadju.

All the women who were shelling cadju had a common complaint — severe backaches due to sitting in one position for long hours.

Once the shelling is done, the kernels are put into the oven provided by the ITDG and heated, then taken out and 'peeled' by young girls who wish to remain in the village without seeking jobs in West Asia or in garment factories.

"This is not a difficult job. I can peel about six kilos a day and earn around Rs. 100, which I use for my personal expenses," says 19-year-old Sudira Iranthi. She had done her OL's but not got through maths. "There's nothing we can do here in Vanathavilluwa, after leaving school. Half the village girls have gone to Puttalam to join the garment factory there. This is better than going to such a factory, because we can live at home," she says.

Yes, it was a remote, border village prone to Tiger attacks, when the ITDG first went there to carry out an evaluation in 1993, says ITDG's Policy Director Vishaka Hidellage. "There was just a small kade and no other development. The International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) and Regional Rural Development Board (RRDB) which were assisting the cashew women with a loan scheme invited us to evaluate the scheme. Earlier we had got a request from the Gampaha area, through Sarvodaya, to develop a drying oven for cashew nuts. That was in the late eighties, when JVP activity and the resultant curfews had crippled most industries, but the cashew industry was doing fine. We found that the industry was hardly affected because it was a cottage industry, and the women could continue their work even during turbulent times."

The ITDG then did the evaluation in Vanathavilluwa and found that most of the cashew women were compelled to sell the raw nuts to the collectors in bulk because they didn't have the facilities to process them. The women were handicapped — they did not have the techonology to dry the nuts without discolouration and damage and get a higher price.

"We decided to help out and after the evaluation made a pilot project of Vanathavilluwa. We provided a dryer on an experimental basis in 1994. The Anagi dryer turned out to be a valuable asset. This type of dryer was in use in Peru using gas or electricity, but we modified it for local raw materials such as paddy husk or sawdust or a combination of both," Ms. Hidellage said.

"In Vanathavilluwa there were several small groups accessing credit, but when we introduced the dryer, they formed one large group. The women had to get together and come to one place to use the dryer, that's how the centre came about. Last year they registered as a company and appointed a management committee with a manager. Now they work in the company they own and share the profits as well. Throughout it has been a participatory approach. In 1995, the women came back with the problem that the dryer was too high for them to place the trays and we adjusted the height. Then the trays were too heavy for them, that too was adjusted."

Earlier, the women had been drying the nuts on the Kabala and scraping the red skin (testa) which damaged the nuts.

She said, "As ITDG's role is usually to provide only the technology, but have as a long term goal the sustainability of such projects, Techno Action was formed before we moved. It consisted of the well-trained extension workers who had been involved with us when we were handling the project directly. Now they act as a small group of consultants based in Kandy, but with support from ITDG, who help out with the technology and also marketing facilities. When we entered the cashew scene to address the quality problem, the Cashew Corporation was dealing with the supply problem. Now Techno Action steps in whenever there is a need.

"Thus, we hope to create a demonstrative effect and promote the cashew industry and replicate it wherever possible. Cashew is an ideal crop for the dry zone where it is difficult to grow other crops and could be used to stimulate the rural economy. Techno Action is already assisting cashew processing in 15 areas such as Anuradhapura, Willachchiya, Mihintale and Karuwalagaswewa benefiting."

Techno Action's W.A. Dhanapala said they provide the technical know-how and training in the art of processing so that the women can get quality cadju. Throughout the process of shelling, drying in the oven, peeling or removal of the red skin, sorting or grading and packeting, Techno Action is there to assist the women.

Those days not even 10 per cent of the cadju grown in Vanathavilluwa were processed in the village, explained the unit's manager, Anupa Tissa, the only man among the 25 women shelling and peeling cashew. "Poverty compelled the women to sell their produce in bulk at once during the season. The middlemen bought the entire stock cheaply."

Vanathavilluwa has a mix of cashew cultivators, big landowners with 100 to 1000 acres and small cultivators with their two to four acres. What the big growers do is stock their produce during the season, which spreads from late March to April and June till August when the prices go up and sell it.

Now the unit buys adequate stocks during the season for processing throughout the year. They stock up the raw nuts, dry them in the sun for three days, then begin shelling. From stocking up to getting the processed cadju it takes 11 months. March is usually left for cleaning the buildings and preparing for the next season. For the 11 months of processing, the unit stocks around 44,000 kilos, with 12 women shelling the cadju and 13 peeling.

Anupa Tissa says that the raw cadju/processed cadju ratio is 5:1. They

sell the processed cadju graded as full ones, halves (splits) and pieces,

to big companies. "There was no specialty in the cadju industry. The whole

family takes to it in this area. But with the setting up of the unit these

women not only have a job where they earn an income, but are also owners/members

sharing the profits," said Anupa Tissa.

Success amidst hardship

A

few miles from the unit, we saw the success story of Monica Fernando, 49,

who has benefited from the technical assistance provided by the ITDG and

set up her own operation.

A

few miles from the unit, we saw the success story of Monica Fernando, 49,

who has benefited from the technical assistance provided by the ITDG and

set up her own operation.

Set

amidst mango and cadju trees, her home of brick and asbestos is under construction,

as opposed to the many wattle-and-daub huts in the area. While Monica works

in a tiny shed at the rear of her home, a parrot in a cage keeps her company,

whistling and talking to her. She learnt much from the centre and keeps

going back whenever they have meetings to show easier ways of processing

the cadju. But she's no longer a member of the co-op system, because she's

able to get loans on her own to process the cadju she gets from her two-acre

plot.

Set

amidst mango and cadju trees, her home of brick and asbestos is under construction,

as opposed to the many wattle-and-daub huts in the area. While Monica works

in a tiny shed at the rear of her home, a parrot in a cage keeps her company,

whistling and talking to her. She learnt much from the centre and keeps

going back whenever they have meetings to show easier ways of processing

the cadju. But she's no longer a member of the co-op system, because she's

able to get loans on her own to process the cadju she gets from her two-acre

plot.

She also buys some stocks from others in the area and employs other women to shell the cadju for her.

The profits made after paying those who shell the cadju and transport costs help educate her two daughters and two sons.

One daughter is in campus and a son is studying to become a technician, she adds with pride.

![]()

Front Page| News/Comment| Editorial/Opinion| Plus| Business| Sports| Sports Plus| Mirror Magazine

Please send your comments and suggestions on this web site to