4th February 2001

Front Page|

Editorial/Opinion| Plus|

Business| Sports|

Mirror Magazine

![]()

Fifty three years of incomplete freedom

By Victor Ivan

The 53rd anniversary of Sri Lanka's inde- pendence

falls today. At a time when the country was going through a transition

from feudalism to capitalism, the expectation of independence was not freedom

from colonialism. Colonialism had created only a modern nationalist state.

In such a situation achieving a national integration required for survival

of a state was an essential condition for true independence.

Sri Lanka had joined history as a country that had won her independence without shedding a drop of blood which means that she has got her freedom on the basis of the kindness of the English and without much effort for winning the freedom and therefore without the conflict that would have otherwise resulted.

If there had been a powerful effort towards freedom, there would have been a powerful necessity to bring the people who had been divided into different groups into a united movement. That process might have minimised such divisions and might have laid the necessary foundation for an integrated nation. The relation between these social groups did not amount to a deep rooted unity. Due to the failure to bring about a united nation, a situation has arisen in which the national state so built is not only in danger of fragmentation, the country which had won her freedom without shedding a drop of blood has become one where the shedding of blood has become endless.

Because any of the racial groups or the leaders who represented them had not been brought up in the lab of a strong freedom movement, none of them had the profound feeling about a national agreement necessary for the survival of the country. The main actors in the political arena at that time were groups who have prospered through economic opportunities that had opened up under the capitalist system which had come into existence during the British period.

Even among them there were divisions in terms of race, religion, language and caste. Although all of them wanted to take administrative power into their own hands after the British, even such desires were affected by race, religion, language and caste. While the leaders of the minority feared a loss of their privileges the Sinhala leaders too tried to win their agreement through deceit instead of taking action to win that consent through dispelling their fears.

The British had followed a policy of divide and rule. Consequently mutual suspicions that had emerged among racial groups had not been dispelled at the time freedom was granted.

Writing a forward to the book "Ceylon: A Divided Nation" written by D.H. Farmer and published in 1969, Lord Soulbury, quoting Sir Charles Jeffries had said that all provisions that could have been made for the protection of the minorities had been included in the Soulbury Constitution.

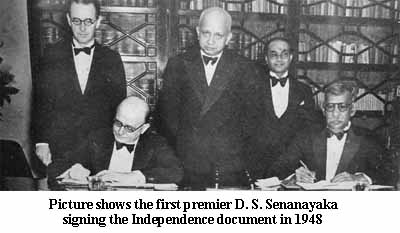

According to section 29 of that constitution it was illegal to enact laws that would discriminate the minorities. However, disregarding these fundamental provisions Premier D. S. Senanayake enacted the Citizenship Act that deprived the workers of Indian origin of their citizenship rights and Mr. S W R D Bandaranaike enacted the Official Language Act disregarding fundamental provisions in the constitution. This shows that constitutional provisions, introduced without a consensus evolved through a deep understanding are meaningless. This fact applies not only to the Soulbury Constitution but also to the new constitution which the PA is striving to enact.

The authors of the Soulbury Constitution had made an estimate of the racial representation in parliament that would be introduced under that constitution. Accordingly, of the 95 MPs elected, 58 were to be Sinhalese, while 15 were to be Ceylon Tamils and 14 were to be Indian Tamils and 8 were to be Muslims. There were to be 6 nominated MPs and the total was 101. The commissioner expected that 43 of the 101 seats in parliament would go to the minorities. However the results of the 1947 election did not bring such a ratio.

The Sinhalese got 68 seats while the minorities got 33 seats only. Due to the Citizenship Act enacted by Mr. Senanayake thereafter the minority representation diminished still further. At the election of 1952, 75 seats of the total of 103 seats including the 8 nominated MPs went to the Sinhalese while the minorities got 28 seats only.

This situation as well as the enactment of laws to the disadvantage of the minorities against the accepted principles of the constitution, did away with even the nominal unity among racial groups at the time when freedom was received, and pushed the Tamil people of the north towards fighting for a separate state.

It would be a mistake to think that this division which has grown after independence could be solved only by enacting a new constitution that would please the Tamil people. If the constitution alone could solve this problem, the Soulbury Constitution which had included all the provisions for the protection of the minorities should have been able to do it. The fact that constitution was now a solution to the racial crisis in spite of all those provisions shows that a good constitution alone cannot solve the problem.

A transformation on the social and psychological plans too is necessary. That is possible only if all groups of people are directed towards acting with great energy for a political aim that can be reached with combined effort. It is then that a socio-psychological environment necessary for national integration would come into existence.

The main question before the country now in regard to this matter is what could bring these ethnic groups who are divided now, together for the purpose of acting unitedly to achieve a great objective. All these sides will be able to attain the knowledge required for national integration only if a situation can be created in which they all will make a collective effort to achieve something great.

The only objective that remains is democracy. The problem of the rights of Tamil people is part of the problem of democracy. However, it is being interpreted, not as a problem of democracy but as an ethnic problem. The Tamil expectation that there should be greater possibility for them to control their own affairs is also a democratic expectation. The expectation that there should be no discrimination is also a democratic expectation.

The war has become a challenge not only to the Tamils but also to the entire democratic political system. If the demand that is emerging from amongst the Sinhala people for good governance that will also address the ethnic grievances of the Tamil people, it might be possible to have a common social movement in which the two divided ethnic groups will work unitedly for a single aim. Thereby it will be possible to develop further the mutual understanding between the two groups and create the necessary environment for national integration.

It will also be possible to create a new political framework in which all communities can function with mutual trust and respect and which will guarantee the rights of all. This process must go forward as a social movement for a second stage of the freedom struggle aimed at fulfilling the aims of the independence which has not been fulfilled so far.

It will be only through a movement that will combine these democratic expectations of the Sinhala and Tamil communities that it will be possible to find a lasting solution not only to the ethnic crisis but also to the crisis of democratic politics that has enveloped the country.

The writer is the Editor of Ravaya

Return to News/Comment Contents

![]()

Front Page| News/Comment| Editorial/Opinion| Plus| Business| Sports| Mirror Magazine

Please send your comments and suggestions on this web site to