|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

A murder retold On a dark, rainy day in 2003, Prof. Ravindra Fernando accompanied by a few colleagues and a Buddhist monk went to Angunabadulla, a village in the Thihagoda area on the Matara Hakmana road, about 168 km from Colombo. “A dilapidated tarred road spreading through green paddy fields led us to Angunabadulla. As we turned our vehicle to the gravel road leading to the temple, an old man dressed in a white shirt and sarong, and carrying an umbrella smiled with the Buddhist priest. That is William, said the priest.” This old man was one of the key figures in a murder trial more than 50 years ago- the Sathasivam case which had grabbed newspaper headlines then and is now the subject of a book by Prof. Fernando.

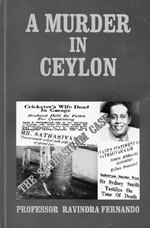

Released last month, ‘A Murder in Ceylon’, Prof. Fernando’s exhaustive account is the story of the murder of Mrs. Anandan Sathasivam, the grand-daughter of Sir Ponnambalam Ramanathan and the 57-day trial that saw her husband, well-known cricketer Mahadeva Sathasivam in the dock. It was while doing his research for the book that Prof. Fernando decided he would like to track down William, the servant boy in the Sathasivam household who had turned crown witness during the trial. William had married and had seven children, one of whom had died of a crocodile bite. Now 76, he was doing odd jobs in the village. “He came out as being very intelligent. He started talking without any hesitation of the murder that happened 52 years ago and kept to the same story he had told court,” Prof. Fernando said.

His interest, he says, was kindled even before he entered Medical School, through newspaper articles which dealt extensively with the case. Later as a student of forensic medicine, he was further intrigued by the complex medico-legal issues of the case. But it was only in 1993 that he found the time to begin his own research.

“Prof. G. S.W. de Saram, the first Prof. of Forensic Medicine in Ceylon carried out at this very Department of Forensic Medicine, experiments on prisoners who had been executed, to enable the determination of the body temperature and time of death of Mrs. Sathasivam,” he said. Another important witness for the defence was an eminent Professor of Forensic Medicine from the University of Edinburgh, Prof. Sydney Smith who subsequently wrote about the Sathasivam case in his autobiography ‘Mostly Murder’ devoting a chapter titled ‘A Murder in Ceylon’ to it. All Prof. Smith’s documents including his handwritten notes and photographs on the case had been donated to the library of the Royal College of Physicians at the University of Edinburgh.

“Initially I only wanted to analyse the expert evidence but then realized that it would not help in the interpretation,” says Prof. Fernando. “It was a sensitive subject and I had to be absolutely accurate.” Recalling the events leading up to the trial, Prof. Fernando believes the public had already tried Mr. Sathasivam. “With Sathasivam, the problem was that he had a motive. He had access to the victim. Therefore people thought he was the person who had killed her. The public convicted him before the trial itself. “The public don’t like killing a woman. Sathasivam was the first suspect. There were no eyewitnesses. The only two adults there at the time were Sathasivam and William. Even some members of the Police and AG’s Dept. genuinely thought that Sathasivam did it, but scientific and circumstantial evidence indicated otherwise. The Police were divided.” “One of the major issues was that Sathasivam loved his kids. If he killed his wife and left, having already sent William out, his two younger children would have been alone in the house with the body of their mother.” Commending the the scientific investigations carried out at that time, Prof. Fernando said the police kept the body at the crime scene without removing it till the evidence was taken. Today they would have removed the body to the mortuary. “The case also showed the brilliance of defence counsel Dr. Colvin R. de Silva,” he said. Sathasivam was in remand for 625 days and Justice E.F.N. Gratiaen commented that it was too long, Prof. Fernando added. What next for Prof. Fernando? He has plans of translating ‘A Murder in Ceylon’ into Sinhala but quips that he hopes it won’t take another twelve years.

Journey through rebellion to fond acceptance The Winds of Culture by Angela Fernando. Reviewed by Salma Yusuf

Coming from mixed European and Asian ancestry, Angela Fernando, born a Singaporean and now a Sri Lankan national, takes the reader on a journey of her life’s experiences. The dominant theme, which runs like a thread through her book, is the conflict of cultures- one she faced at many points in her life. The Winds of Culture, is almost autobiographical and follows a chronological sequence in presentation. The writer goes back to her early childhood in pre-World War II Singapore, from where she fled after her father was captured by the Japanese as a Prisoner of War to the harsh circumstances of living as a refugee for nearly two years in India, and lastly to boarding school in Western Australia which she recalls as the best years of her life.

After her matriculation, she entered the University of Melbourne where she met Jerry Fernando, a Sri Lankan, who would become her husband. She recounts the divergence in cultures which caused setbacks in her relationship with him-from being rejected by his family for being a foreigner; to expectations from her conventional husband to wearing a saree; and sporting a ‘konde’. But her great love for her husband and his for her, helped them bridge these differences. Her inspiration to write the book came after her husband’s death, when she felt the loss of a buffer factor which had until then helped her to bridge the cultural divide to a great extent, Angela explains. “In writing this book, I decided to explore the culture myself and gain greater insight into why people think and act the way they do in this part of the world,” she says. She points out essential driving forces that cause the difference. “In the West people keep up with modernization and progress whereas Asians lean more towards maintaining customs, habits and norms which are often accepted merely because it has been practised by their forefathers. This is rarely compromised in any situation.” She also highlights how the Asian lifestyle is far more personalised than the Western and how she has grown to love the former. For instance, when you go shopping in Sri Lanka you learn that the fishmonger has nine children; the vegetable vendor’s mother-in-law has run off with someone or that the butcher up the road has hacked his rival with a hatchet. There is also a touch of satire in her writing when she highlights the hypocrisy of rabble-rousers who scream at the West but educate their children in Colombo’s international schools. On the other hand she excludes pseudo western Sri Lankans, whose lives revolve round parties and other socialite functions as being ‘truly Sri Lanka’. She also recounts how she discovered cultural differences through day-to-day incidents. For example how she had to discontinue the practice of carrying on discussions with colleagues sitting on a tombstone in a cemetery close to her university in the West, once she came to Sri Lanka as the cemetery is seen as a place to be avoided; to finding out that killing oneself over a doomed love affair was quite common here but almost unheard of in the West; the warmth of Sri Lankan hospitality where no visitor is allowed to leave without joining for a meal if they happened to visit at meal times; to how her mother couldn’t come to terms with the fact that she had to eat with her fingers and gave her a set of cutlery as a parting gift. Through these sometimes humorous episodes she explores a deeper theme of how one’s way of thinking affects the fundamental behavioural patterns of different cultures and the sacrifices one has to make to adjust and understand. The reader can almost feel the metamorphosis the writer undergoes, from a questioning rebellious individual to that of resignation and eventually an understanding and fond acceptance of the differences. She says her challenging experiences led her to ensure that her six children married into the same Asian cultural background so that they would not have to undergo the same kind of sacrifices and adjustments she had to make in her life. “I am happy with how my children are living their lives. I didn’t want them to experience the cultural adjustments I had to go through,” she say. The first person narrative style adopted by the writer makes the novel both entertaining and very personal. At different points in the book, the author digresses to her children and friends. Part of the book is dedicated to her handicapped son, JJ, a lesson in love and patience. In her postscript, written after the tsunami, which killed many in her family, Angela considers revising her way of thinking . She says the winds of culture blew away any differences that existed over the years in her mind. She grew to realize that man’s humanity overrides everything else. When asked why she decided to continue her life in Sri Lanka even after her husband’s death, she says with much conviction, “when you marry for love, you don’t cut off connection with everything that is essentially him, after he is no more….” |

||||||||||||||||

Copyright © 2006 Wijeya Newspapers

Ltd. All rights reserved. |