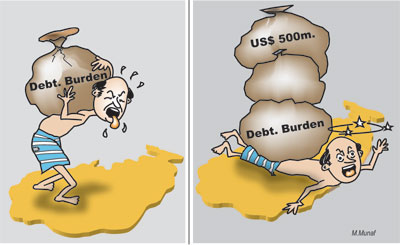

Foreign borrowing: When the costs outweigh its benefits

Last week's column dealt with some of the issues involved, but there appears to be a need for further discussion of them. Stated simply the issue is whether further foreign borrowing of the envisaged magnitude would bring in adequate benefits outweighing the costs of such commercial borrowing. These costs however are not merely the financial costs, but the costs that the economy may be burdened with owing to consequent bad economic policies. Professor Raghuram Rajan of the University of Chicago delivering the Central Bank 57th Anniversary Lecture last week sounded a word of caution when he said that it was better to rely on domestic savings rather than foreign funds for investment. He said that international experience had shown that developing countries that relied on large foreign borrowing had not benefited much. This he adduced to two possible reasons: financial sector underdevelopment and currency overvaluation. The second factor requires some elucidation. Large scale borrowing could have a negative macroeconomic effect that economists call the "Dutch disease". What it means is that the comfort of foreign funds results in the pursuance of wrong macroeconomic policies. Corrective actions in fiscal policy and money creation are avoided. As a result there is an appreciation of the exchange rate when the fundamental weaknesses require a depreciation of the currency. Consequently this results in a "tax" on exports and subsidisation of imports. This in turn contributes to a widening of the balance of payments deficit. In order to avoid such an eventuality the country will need to devalue the rupee which will bring in a further bout of inflation, contributing to another round of Balance of Payments worsening and distorting real prices. In fact when governments get large sums of foreign exchange, either as loans or windfall gains, they follow the opposite policies than those required. They opt for palliatives for the current woes rather than the correction of fundamental imbalances in the economy. In fact developing countries should access foreign funds for achieving higher levels of economic growth. However, these funds should be borrowed at lower rates of interest and on long periods of repayment. They should be used for productive purposes and as much as feasible, for the production of tradeable goods. The resort to foreign borrowing can be an important means of supplementing domestic savings and thereby be a means of enhancing investment and economic growth. At early stages of economic growth domestic resources are very inadequate to propel an economy to high levels of economic growth. Therefore foreign funds are a vital source for investment. The supplementary foreign resources come in several different forms. Foreign aid, foreign grants, loans at concessionary interest rates, foreign direct investment, portfolio investment and commercial borrowing. The conditions of borrowing such as the interest rate, terms of repayment and the amount of borrowing have an important bearing. The accumulated debt and the debt servicing cost is also an important dimension. Besides this an all important issue is the use of the borrowed funds. Though the purposes for which foreign funds are used are of vital importance it is this aspect that is often neglected. All these issues are of significance in the context of the new endeavour to borrow a large sum of US$ 500 million on commercial terms. Owing to such policies at the end of last year, despite some commercial borrowing recently, the foreign debt that was Rs.1131, 074 million consisted mainly of concessional borrowing. As much as 92.4 percent of foreign loans or Rs.1045, 346 million had been borrowed on concessional terms. Consequently the foreign debt servicing absorbed only 7.1 percent of the value of exports. This favourable picture may be changing. The foreign debt has been increasing recently. By the end of May this year the foreign debt had increased by nearly 20 percent (19.6) from what it was 12 months before. In the five months after the end of last year it had increased by 7 percent. The proposed loan of US $ 500 (approximately Rs. 550,000 million) would raise the debt appreciably and change the composition of the debt and debt service costs significantly. The new loan at higher interest rates and shorter maturity would raise the debt:GDP ratio as well as the foreign debt servicing costs, it would increase the annual amortisation costs as well as the interest payments and reduce the average maturity of the foreign debt portfolio. In short the country's foreign debt burden would be increased. This may be quite clear to everyone. The real issue is in fact with respect to the utilisation of the loan funds. And this is the aspect that tends to be most neglected. The simple fact is that if the funds are used for investments with a high return and those that produce exportable goods, then the debt burden would be increased only for a brief period of gestation of the investment. The real danger lies in the use of the funds for consumption rather than investment. The worst scenario would be its use for military expenditure that is not economically productive. To the extent that it is for military hardware imports, even the immediate benefit to the balance of payments by the inflow of funds would be negated by the outflow of funds probably in a very brief period of time. To the extent that it is used for domestic expenditure in the war it would be inflationary. The government claims that the funds are for infrastructure expenditure. If this be the case the financial implications are only slightly better. Infrastructure expenditure is very costly and brings in returns only over a long period of time. It may in fact not contribute to an ultimate reduction in the foreign debt servicing burden, if the long run increases in production are not of tradeable goods or exports. The other danger in the availability of these funds is that the government's fiscal discipline could be eroded. People may be given a feel good feeling when in fact the economic situation is deteriorating. Priorities in public expenditure could be distorted; pricing policies for imported goods may not be adjusted to international prices and wasteful government expenditure cold increase. All these would have a heavy burden on the economy later on. Borrowing at commercial rates and short periods of maturity for purposes that don't yield exportable goods could result in the country being caught up in a debt trap. Would the costs of foreign borrowing be justified by the sensible use of the funds so borrowed? |

|| Front

Page | News | Editorial | Columns | Sports | Plus | Financial

Times | International | Mirror | TV

Times | Funday

Times || |

| |

Copyright

2007 Wijeya

Newspapers Ltd.Colombo. Sri Lanka. |

Foreign borrowing has become an intense topic of discussion these days in and out of Parliament. The advisability of foreign loans has come to the forefront of discussions with the government's intention of borrowing US$ 500 million from the international money market. As is often the case political issues cloud the economic commonsense.

Foreign borrowing has become an intense topic of discussion these days in and out of Parliament. The advisability of foreign loans has come to the forefront of discussions with the government's intention of borrowing US$ 500 million from the international money market. As is often the case political issues cloud the economic commonsense.