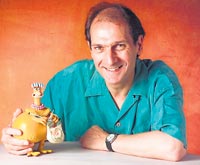

Magic of moving modelsDavid Sproxton of Chicken Run fame who was in Sri Lanka this week, talks about thehobby that has now evolved into a globally sought after Aardman Animations. . David Sproxton knows what it takes to create on-screen magic – endless patience, sweat and tears, clever illusions and sharp humour, finely honed skills and an unbridled imagination. As one of the founding directors of Aardman Animations, he has spent a lifetime building what is now considered one of the pre-eminent production houses, not just in the U.K, but in the world. Having served not only as producer, but as a director and cinematographer for several of Aardman’s films, David has worked on some of the most popular animated films in recent times, including “Chicken Run”, the Wallace and Gromit shorts and feature films, as well as one of last year’s most popular releases, “Flushed Away”. In the process, he has not only collaborated with some of today’s hottest stars, he’s also seen Aardman walk away – more than once - with the most coveted of awards – the Oscar.

“We celebrated our 30th year, last year, and we put together a compilation of material,” says David, adding “it’s quite scary to see your life flashing before your eyes.” And it’s been quite awhile. Aardman began rather humbly as a hobby indulged in by two teenage boys – Peter Lord and David who were only 13 when they first began “messing around” with a 16mm film camera. More than a decade later, the two would form Aardman, and go on to collaborate with Nick Park on “Creature Comforts” – the short film which would bring them international recognition and their first Academy Award. Having now come to the attention of the big American studios, Aardman eventually signed a contract with Dreamworks – the studio founded on the vision of industry giants Steven Spielberg, Jeffrey Katzenberg and David Geffen. More recently, Aardman has signed up with Sony Pictures Entertainment. Both partnerships have helped Aardman become a global player, with devoted fans all around the world obsessively following the adventures of Aardman characters like Wallace and Gromit. Part of Aardman’s appeal is in its quintessential British-ness. Wallace for instance, absent-minded inventor and cheese enthusiast, can usually be found wearing a white shirt, brown wool trousers, green knitted pullovers and a red tie. His love of a Lancashire hotpot is as predictable as his tendency to land himself in a dreadful muddle – from which only Gromit, his considerably more intelligent pet beagle, can rescue him. David and his team cut their teeth on stop motion productions like this. And though they can be arduously time consuming and labour intensive, he still has a soft spot for them. This type of animation uses models and sets, moving each object by very small amounts between individually photographed frames - a process which results in the appearance of motion when the frames are played in a continuous sequence. “The great thing about having little models as your actors is that they don’t get stroppy and they don’t go off to their caravan,” says David, reflecting on the many varied pleasures of working with clay models. “And of course you have total control,” he adds, “so it’s a bit like playing with dolls, really, but there’s an intrigue and a fascination.” Both of which are feelings shared by the public, who throng to exhibitions where the small, exquisitely detailed models, and the accompanying sets, including lush gardens, and solid manor houses, are put on display.

Technically, stop motion animation is quite challenging not to mention time consuming, he reveals. Shooting at 12 frames per second, a crew might only get 3 to 3 ½ seconds done per day; and when you consider that what with set ups and test runs, actual filming might take place only for a day or two every week, a feature length film becomes a protracted undertaking. Frames must also be shot in order, and so an animator needs to have a clear idea of the sequence of events. “It’s like a very slow motion performance – you’re going to have to know where your characters are going to get to, you’ve got to see it in your head.” “Some [animators] are actually actors, and some I don’t think you’d get on a stage in a million years, but they all express themselves through these models,” he says. Apparently, model’s limbs can all move, and are adjusted for each new take. However, the mouth sections can be pulled out, while animators choose a new set of lips from a waiting selection of “pre-made mouths,” all of which are designed to simplify the process of lip syncing. However, with characters like Gromit, who don’t have a mouth, all the action is in the eyebrows and ears. Body language is everything. “We often tell our script writers, ‘no we don’t need to say that, we can do it with a look,’” says David. In other areas of the production as well, the god is in the details. Animated shorts and films are famously choc-a-bloc with subtle gags - Wallace might be reading a book titled “Waiting For Gouda” or Mel Gibson might attempt a comedic repetition of his famous war cry “Freeeeedom,” when voicing Rocky the rooster’s very brief flight. While these little touches are sometimes woven in while writing the storyboard, more often than not, they’re the result of “secondary thoughts, that go ‘ooh let’s do that gag’,” says David.

It’s apparent that for him, stop motion animation is a fun process at every stage, from story board writing, through model making, set construction and camera work. However, technology has moved on, and stop motion animation no longer rules the roost. Aardman, along with most other production houses, have begun to use Computer Generated Imagery (CGI) or 2D animation quite extensively. “Software has gotten better, cheaper and now there are more people who can drive it,” says David, reflecting on the sudden flood of animated movies into the market. The demand remains high, with multiple T.V channels and increased numbers of cinemas and multiplexes worldwide. In a rush to meet this demand, Hollywood has fallen back on its most beloved theory – “if you’ve got an idea that works, keep doing it until the audience get bored. ” For production houses like Aardman, standing out from the herd is now not only a matter of creative content but forming the right alliances with big time American studios, who can afford extensive marketing and have large distribution networks. Fortunately, such alliances have paid off spectacularly. Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Weir-Rabbit, dubbed the “First Vegetarian Horror Film,” won Aardman their fourth Oscar. The list of stars who’ve voiced Aardman’s character’s include several famous names like Mel Gibson, Hugh Jackman, Ralph Fiennes, Ian McKellen, and Helena Bonham Carter. And even there, David found that they were working with long standing fans. In the end, however, all the glamour comes only after a great deal of hard work. The good news is that, with a rapidly expanding international fan base, Aardman has nowhere to go but up. |

|| Front

Page | News | Editorial | Columns | Sports | Plus | Financial

Times | International | Mirror | TV

Times | Funday

Times || |

| |

Copyright

2007 Wijeya

Newspapers Ltd.Colombo. Sri Lanka. |