In the dead of the night of March 12, somewhere in the middle of the Indian Ocean, a container ship found itself engaged in a potentially deadly game of cat and mouse with a gang of Somali pirates.

As the two small pirate skiffs chased down their quarry, the ship's captain desperately attempted to throw them off, increasing speed and trying to destabilise the smaller boats with waves from his hull.

The pirates opened fire on the ship, but were eventually forced to abandon their assault. As they disappeared into the darkness, the shaken captain logged his position and reported the incident to authorities.

In many ways, the attack had followed an all-too familiar pattern; pirates in small, mobile craft attempting to board a larger vessel to hold it for ransom.

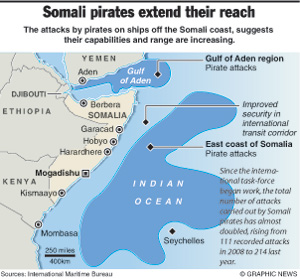

But in one important respect, it differed from the norm. It had taken place in a stretch of ocean between the Maldives and the Seychelles, more than 1,000 nautical miles from Mogadishu, the capital of Somalia.

On March 23, the pirates struck again, this time successfully hijacking a Turkish-owned ship 1,100 miles from Somalia's coastline. On the same day, another ship was seized off the coast of Oman.

The hijackings, the first of which took place closer to India than Africa, are proof that the Somali pirates have expanded their operations further from land than ever before.

Victims of success?

Experts believe that the introduction of an anti-piracy naval task-force to the Gulf of Aden, the favoured hunting ground for maritime hijackers, has forced the pirates to push into new areas in search of ships to target.

"They have moved further out into the Indian ocean, away from the patrolled area," Captain Pottengal Mukundan, the director of the International Maritime Bureau, which logs pirate activity, said.

He now describes the problem of Somali piracy as an "unprecedented criminal phenomenon" that has developed at an alarming rate.

|

| Somali pirates have extended their operations further into the Indian Ocean |

In 2008, pirates were operating with practical impunity in the Gulf of Aden, prompting a UN resolution that mandated the launch the naval task force in the region.

The warships have played an "absolutely critical" role in preventing successful attacks in the area, Mukundan said.

But outside the heavily patrolled areas, a different story has emerged.

Since the task-force began work, the total number of attacks carried out by Somali pirates has almost doubled, rising from 111 recorded attacks in 2008 to 214 last year.

An increasing number of these are taking place in less heavily patrolled areas, with strikes occurring as far away as the coasts of Tanzania and Oman.

Shipping in the more remote parts of the Indian Ocean, it seems, has fallen victim of the success of the naval patrols to the north.

The attraction of these new areas to pirates is clear. Ships crossing the Indian Ocean tend to follow set routes, making them far from help and easy to find.

With millions of square miles of open water to hide in, the pirates, who launch raids from larger "motherships" that can remain at sea for long periods, remain confident of avoiding the detection of the authorities.

Once in place, the pirates simply sit back and wait for their prey to appear, and they are not fussy about their targets. "They are opportunist," Mukundan said. "They go for whatever ship they can get."

With the winter monsoon coming to an end, experts are expecting a rise in such open-sea attacks as the weather improves.

"We're expecting the pirates to go after the ships with renewed energy," Mukundan said. "The robust targeting of motherships is key to solving this problem."

Answer lies on land

But patrolling such a large area is an enormous task, and one that some experts believe is futile.

The real answer to the problem of Somali piracy lies firmly on land, Roger Middleton, a researcher on the Africa programme at the London based think-tank Chatham House, said.

In war-ravaged Somalia, which has not had a functioning government since 1991, his assessment is bad news for those hoping to end pirate attacks in the Indian Ocean.

"If you woke up tomorrow, God forbid, as the Somali president, piracy would be far down your list of priorities," Middleton said. "Piracy is not the biggest problem in Somalia."

"If you're going to get shot at, why not do it out on the ocean where you have a chance of making an enormous amount of money?" Middleton said, explaining the logic that drives people to piracy.

He argues that unless some sort of stability can be brought to the country, young men who have only a life of violence and poverty to look forward to will continue to see maritime crime as a golden opportunity.

Lack of will?

Daniele Archibugi, a professor of public policy at the University of London's Birkbeck College, agrees with Middleton's assessment. "To fight piracy, we must stop the civil war in Somalia," he said. "Do you think the international community is willing to do that?"

He believes a purely military response to the problem will ultimately fail to bring it under control. "The navies are equipped with the latest technology, the best equipment and what can they do? Nothing," he said.

"No more than 1,000 young men have managed to put the most important maritime route in the world into crisis."

It is a crisis that has thrown up some hard choices. The naval flotillas have gradually shifted their areas of operation in response to the pirates' changing tactics, and there is concern that such "mission creep" will result in spiralling costs and an impossibly large area to patrol.

The viability of the naval option may be uncertain, but with no sign of peace coming to Somalia in the near future, representatives of the shipping industry believe it is the only option.

Shipping experts say that if left unchecked, the effects of Somali piracy will soon be felt around the world.

"Everything that we have, from the coffee for your breakfast to the fuel in your car, comes by ship" Mukundun said. "We need a robust response."

Courtesy Aljazeera |